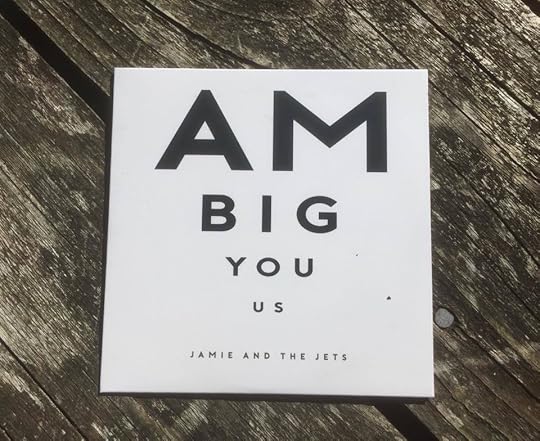

Interview with a Songsmith: Jamie West’s 2018 launch of AMBIGYOUUS by Jamie and the Jets

WS: Tell us your name.

JW: I’m Jamie West. I’m a guitar teacher in the day, by

night I write songs. Yep. I love writing songs. I’ve done it since the age of

thirteen, when I learnt to play guitar. It’s a great creative output. I enjoy spending

time in the studio putting them together.

WS: April 2018. We’ve

just sat in my front room, listening to the album, while eating scones—

JW: —magnificent scones.

WS: You’ve given me

notes, just for the song titles, in red and pink.

JW: The red ran out, so I went into pink.

WS: What’s the album

called?

JW: It’s going to be called AMBIGYOUUS

WS: When you told me

that earlier, I didn’t know that U was YOU.

JW: Yes. I am big. You. Us. It’s one of those happy

accidents of a word.

WS: Which you also did

with Sic-Amor. Introduce us to AMBIGYOUUS. When did it begin?

JW: I’m always writing songs. I just collect them. I try and

work on a yearly cycle. In finishing an album, I look at my next project. I

realise I’ve collected five or six songs; I’ve started to record and shape

them. From there, I just add to it, like a folder on computer. And I keep

adding to it, and that becomes the next collection of songs. Equally I’m not

afraid to finding old songs which I think are worth revisiting. There are three

songs on this album which date back…well, one of them to my late teens.

WS: What For? And Orange Orange? That was new when we met. [We argue for five minutes

and decide it was somewhere around March 1995.] I like the idea of the folder

on your computer. But there’s also in your brain a folder: probably has 20 or

30 ideas.

JW: We’ve been discussing how some ideas get legs and some

don’t. Depending on what mood you’re in – or luck. But because time is

precious, and I’m not doing it full-time, you make a mental process about what

you’re willing to commit to. You’re doing editing up front, as opposed to

writing and finishing 20 songs and getting rid of six or eight. You’re saying

up front, “What have I got the energy to do? Where do I see this going? What do

I have a bigger production idea of? Can I see it finished?” If the answer’s

yes, you put your energy there.” So the folder ends up nowadays sparser, rather

than in the old there would have been more starts to songs.

WS: When they release

your anthology, there may be some fully-fledged songs that never made it, but

it’ll be mostly noodles and nurdles.

JW: Yes. Oh, it’s worth saying, for the header notes: We

made a conscious decision. For my fourth album, Hypnagogic, I worked with

yourself William Sutton, Sarah Prosser and Rosie Holmes. They became the Jets,

the band I play with now. We had a conversation about contributing to the

album, and playing on it more, and having it as a Jamie and the Jets album. I’m

pleased about that. It’s been a very

enjoyable experience.

WS A few of the songs

we’ve been performing for a while. It evolved organically. Others we just did

in the studio. Great.

That Was the Day the World Stood

Still

WS: Okay. Am Big You

Us. Typically I know some of the songs, but I don’t know the titles. World

Stood Still?

JW: That Was the Day

the World Stood Still. That’s going to be the exit song of the album. It

has that sort of statement. It’s the name of a famous film or book – which is a

cliché and I enjoyed that.

I was sitting in Pie

& Vinyl which is a fantastic shop in the heart of Southsea. What makes

it fantastic is: that it has a bi-use: it sells pies and records. That’s such a

good concept. There should be more shops with dual functionalities. I’m sitting

there with my son Alfie; he’s 18 at the time. We’ve had a day out. He loves

eating a pie. There’s this lovely female artist – they play records obviously –

just washing her way through the speakers. I’m facing the window: Castle Road.

You can see the people walking up and down. I realise how calm I feel. How

serene it feels, spending the day there with my son. I form the lyrics in my

head. There and then.

Didn’t write them down.

I could recall them. I do a thing: it’s like saying a times

table. I say them over and over to myself. And have key words which will help

me, with the rhymes.

It was about feeling completely serene and at peace with

myself. A rare feeling for me. Then listening to the song where there’s this

great sonic explosion. It signifies a return to that anxiety.

WS: It made me

anxious.

JW: It’s supposed to be threatening.

WS: The remembering

thing: you remember one of the rhymes and it keys you in?

JW: I don’t thinks there’s many rhymes. That’s a challenge:

to remember the first line of the song. ‘I was invisible…’ I would just

remember things like that, being invisible. ‘I sat inside my dream, it knew me

well.’ If I remember sitting in a dream, and feeling comfortable, that’s the

way I’d remember the line.

Please Don’t Let Me Be the One That

Has To Tell You

WS: Oh, that’s with

Clifford? Tell us about the song.

JW: The song was composed thinking about a relation of mine

who was overseas, who was struggling with how to get their head round a

situation. I’m reflecting on their life, their personality.

I run an open mic night at Harting Roundhouse. It’s completely acoustic. These fantastic

musicians come along. One such musician is a chap called Clifford dSouza. He has

this lovely Damien-Rice-esque voice. I wanted to capture his voice. He’s got

such a warm singing voice. If singing is an expression of your soul, I get the

sense he’s got a disproportionate talent. I feel so embodied and warm close to

him in his expression.

WS: And we all come

out wanting to give him a hug. It’s a nice line, the title.

REVERENTIAL

WS: Reverential is

next. The notes say, Vox is loud.

JW: Those notes are diminishing. They’re the fifth set of

notes. You can read back and find earlier notes.

Reverential: the verses are a five-part story about my brother,

my son, my wife, my daughter and then my wife again. I was noodling on an open

guitar riff, a John-Martyn-type riff. All I could keep singing was ‘sentimental’.

I took the word sentimental away, and wrote down all the rhymes I could find

with it. I quizzed myself whether I could write a scheme. It’s quite an odd

word to rhyme with. More often than not, if I get a first verse, I can pursue

it. The first verse came. And the chorus became a theme about having dreams as

a young person. And the choruses allude to losing your dreams and not losing

your dreams – through life – how satisfied and dissatisfied you are about that.

Did you aspire to what you wanted, or did you not?

WS: I’ve played and

sung this with you a number of times. I hear some verses and not others. I

always hear the verse about your daughter, which is lovely. ‘Still a little

temperamental’

JW: ‘Our princess grew into a queen / So beautiful and so

serene / She rattles like a tambourine / Her head is filled with all these dreams

/ Still a little temperamental’.

I feel blessed that the lyric came out with this stupid

rhyme at the end, but it came out honest. It nourishes her. It lets her know

that I love her, but I’m also getting a little dig in. Which is like me, I’m

afraid. Giving with one hand, taking with the other.

WS: I love the

choruses as well. The jeans…

JW: ‘What happened to those days? / My stolen jeans and your

mix tapes.’ I’d love to write narrative songs, like Chuck Berry or someone. But

I admire someone like Thom Yorke who just put in one line in a song – or Biffy

Clyro do it – that is a scenario and makes your mind wander. These stolen jeans

– who stole them? Have I stolen them? Morrissey sings about stealing clothes

from a washing line. That’s brilliant. Mix tape – alludes to a certain

demographic. Only certain people know what that means. If you’re sixteen years

old and you ask your dad, what’s a mix tape? That’s a nice little story.

WS: At the end of the

recording of us playing it in Clerkenwell Arts Lab, you can hear John Hegley

sigh: “Ahh!”

JW: The made-up word lamentful – there’s no such word. You

can have lament, lamenting, lamentable…

Someone Like You

JW: I’m going to ask you a question. You said, in the

musical of my life, they’d use that song. What did you mean?

WS: I meant, some of

your songs are difficult to put into a narrative arc (like Mamma Mia). That

one, the male lead will be walking beneath the balcony of the woman he loves.

Then we’ll realise she’s singing the same thing. He will sing a verse; she will

sing a verse; then they will sing together.

JW: You’re saying the heroine is singing the same song.

WS: That’s the trick

of putting it into a stage show. You give two sides to it. Like Something

Stupid: we suddenly realise that they both think the other is amazing while

they themselves are unlovable. [Witters on about the Bob Dylan musical.]

The guitar is clear

and bright and warm and kind. The voice goes with it. It’s unusual for you to

play and sing the same notes.

JW: It was written like that. Often when I finish work, in

the hall where I teach, I will just sit and play guitar. If I find a vein of

something I like, I’ll pursue it.

I must have just been playing that riff. I was playing a G

chord. You can play it with free fingers, to play a little melodic pattern.

That’s where it came along. I was keen to find the words to fit the melody that

I’d written on guitar. I was happy just to sing along with it.

Normally I just play a block chord and find the melody of my

own. Like a bridge between two chords.

WS: Right. There are a

few pop song writers who write a tune, but most are hummers. [They chatter

about Jacques Brel, Billy Mackenzie, Paul McCartney, and Yesterday.]

I’ve heard you sing it live, have I?

JW: You commented about the critical voice of my own,

questioning that, the first time I played it to you. It’s a very – how to say

this? when people are abusers or drunks, they have this remorseful side,

they’ll come back and they’ll plead forgiveness. Promise never to do it again.

It’s taking that type of a role – I’m unlovable (as Morrissey goes on about it).

It’s not exactly true, but it’s an aspect of who I am. It feels honest to say

it.

WS: My wife is always

analysing your songs.

JW: In what way? For you, or for me?

WS: About you and your

wife.

You Only Made It When You’re Dead

JW: I have a diary every year for my bits and bobs. In a WHS

Smith diary, at the bottom of each week, they have a quote. I was drawn to… Jimi

Hendrix was quoted as saying, “You’ve only made it when you’re dead.”

Beautifully ironic, because he, like Kurt Cobain, and those

other people, died very young, and was extraordinarily talented. If he had

lived, would he be as famous? Such a bittersweet ironic comment for someone to

have made who shone so brightly and so strongly. In my world, Jimi Hendrix took

the guitar into the stratosphere. I’m not a particular fan of his, but I

understand his position in the Hall of Fame.

I love that quote. I’ve always toyed with this idea about grief,

human grief, when people die. We should celebrate people when they’re alive.

Tell them you love them when they’re alive.

The song is simple. It paints the story of Jimi Hendrix

visiting me in a dream. And he speaks to me. Then I want to see him again, because

he’s comforted me. And then “You’ve only made it when you’re dead” is just a

nice quote. It pays homage to him. And it makes a nice loop in my mind: there’s

me, a guitar player, referring to another guitar player.

Sonically, my band Lewd, we were a quite loud band. We’d enjoy

that. Playing a subtle melody, then exploding. The song is a hangover from my

Lewd days. Paul the singer would love singing that, love the anthemic stadium

guitar part. We enjoyed rocking out to that onstage. I’ll dedicate that to him.

Never got recorded. Played it live a lot.

OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder)

JW: Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. These things get bandied

around by all and sundry. If you really do have OCD, it can be quite frustrating

or insulting. It’s a joke like that. It’s just a big long line about

self-diagnosis. About being a hypochondriac – but mentally. Cramming all those little

disasters in there.

Musically it was a completely different song when it

started, different words. I like the double gospel ending. And I like the way

the band added to it and made it more gospel.

WS: … What did we

do?

JW: With the backing vocals. Sarah came in and decided to do

it as an echo, filling in the space. Those changes are quite gospel. C, D, E

major. Doesn’t resolve. Modulates between E flat and G. It does the ending

twice.

OCD might get called Mary-Jane.

WS: And Mary-Jane is a

self-prescription?

JW: Just a lyrical luxury. I don’t know anyone called

Mary-Jane.

WS: The piano, the

rollicking piano. Is that where you wrote it?

JW: Yes.

WS: It would be fun to

play it live, with a piano.

In the Shadows

JW: Back in the Lewd days, we had a website. I wrote the

sleeve notes, if you like, for that website. I described our music as… If you

imagine the bed of the forest, the floor, in the winter in the northern

hemisphere, there’s no canopy on the trees, and the light gets in, so small

flowers grow. But as the canopy develops in the summer, the floor of the forest

is in the shade, so it doesn’t support all the life and flowers. That’s the way

I felt about our music and the way we tried to access our expression – it was in

the shadows of bigger trees.

So I wrote a song about that. It’s a song of optimism

actually: about how small flowers grow in the shadows of bigger trees. That’s

an optimistic message. The lyric is ‘in the shadows’ and ‘in the shallows’.

That’s the same thing: on the edge of the water.

WS: I hadn’t noticed that they were kindred words. It’s nice

when a song brings that to mind.

Best Friend

JW: We’re on an artists’ weekend, as we record this. There

are four of us who get together. The last time was a year ago, April, in

Salisbury. I had written this song. I have a friend called Mick. I made a joke

about him once, saying, every time he tells me a joke, I go and tell it to all

his friends. I had this concept of stealing his personality. I used to taunt

him, that: I tell it better than you, funnier than you. In my mind, he’s my

ghost writer, if you like. I take his material and I embody it.

It’s about that borderline stalker-murderer type person. I had

fun with inventing a character. It’s not about me, it’s not autobiographical;

though there are elements in it… The story about the girlfriend… about

getting a sexually transmitted disease from your girlfriend, that happened to

my two brothers. My eldest brother, I used to steal his trousers. We’re both tall

people. It’s very convenient having a brother with the same length leg as me,

because it was difficult to find in the shops; he was the best place to get

clothes from. So I did walk around the house ‘Like I was in his skin’. That’s a

truism. But it doesn’t belong to me in this story; it belongs to the character.

Musically, the production is warm and nice. One of those

songs that makes me musically smile. I find it satisfying. It’s simple

chordally, but nice.

Orange Orange

JW: When I wrote Orange

Orange, I used to have 5 reasons I told people I wrote it. I can’t remember

all five.

Famously, ‘orange’ is one of those words you’re always told

nothing rhymes with it. But ‘orange’ rhymes with orange. ‘You said it couldn’t

be done / Maybe I did it just to prove you wrong.’ It’s a song about writing a

song.

Apples are green, lemons are yellow, oranges are orange.

Oranges are cool: Orange amplifiers, Orange County, Oranges are Not the Only Fruit. It had

an element of coolness. That’s how it led to being a funk song, with a big old

fat guitar riff.

That’s enough reasons. I wrote it as an exercise. It’s

meaningless. The lyrics don’t mean anything. Don’t tell a story. It’s just a

big funk jam with some lyrics. We’ve always had fun playing it. I’ve always

played it with you. It felt right to put it on the record because we’re playing

in a band together.

WS: There are lots of

funk jams that the content is in the way you do it. ‘Maybe I did it just to

prove you wrong.’ There’s a relationship hidden in that. It’s satisfying to

play the bridge – if that’s what you call it.

JW: When you write songs, you get caught up in being

autobiographical or cathartic. Which is brilliant and has always helped me to

have that outlet. Just to write some nonsense is equally pleasurable sometimes.

And Geoff likes it.

WS: Interesting.

Mend in Time

JW: Mend in Time

is simple lyrically. About my son Alfie who was 18. He had a girlfriend. First

proper relationship he had. He wanted to take her out for her birthday, really

make a fuss of her. Again he was playing out the role of what it was to be a

boyfriend, have a bit of money, take your girlfriend out. Her birthday happened

to be New Year’s Eve. They all went out. I think, it all went a bit wrong.

Expectations weren’t met. Then the relationship ended. I saw my son broken-hearted

about it. Just reflected that in the son.

Musically, it’s interesting. I had a guitar riff in 5/4. As

a songwriter, musically, you’re always looking for little ideas to change something.

When you come across a different time signature, that’s always inviting if you

can make it work. Not just to show off, as a technical exercise. The way you

pick the first three strings going down, you can make a 5/4 rhythm. So it was pleasing

to come together with that lyric.

In production, it was fun, because we got you to play the

double bass – bowing it – that was the first time we’d used it. That was

brilliant fun. Rosie put on a fantastic harmony – Sarah played a fantastic cor

anglais solo. It was magical the way it came together. It mixed itself, in a

way.

WS: Yes, that was

challenging. That’s my high point of the album, today. It’s a 5/4 that I didn’t

know there was anything odd about, on first listen, which is a great thing to

pull off. It’s melancholic, there’s something about the steps down of the

chords, G to the F, sometimes an F#. I don’t understand it.

JW: When you play in G major, the fifth in D major and has

an F# in it. When you play in G minor, and you play a harmonic minor, you have the

same trick. You have a G minor or a C minor, but you can play the D7 with an F#

in it: that way you can take it back to the G major or G minor. It’s just a

trick, isn’t it?

WS: In your notes, you

write “My voice could be more like this in other songs.” Meaning?

JW: It’s bassier. It’s warmer.

WS: And that’s the one

I was saying that Rosie’s like the cream to your strawberry jam: the two vocals

together go really nicely. Apart from her matching you incredibly closely,

which is a good skill. She’s got a lovely, odd harmonic sense.

JW: She sings a major note at the end of a minor section,

which is fantastic. And we have to credit Rosie, when Sarah puts her cor

anglais solo down, Rosie’s made a three-part vocal piece to support it. A vocal

organ. Adds a bit of gravitas. If that’s the right word.

WS: It’s a good word

for the song. The song has unusual gravitas. In your oeuvre. Which sounds like

an insult, but isn’t.

What For?

JW: It’s an old song. I wrote it in my teens. Nineteen,

maybe? Lyrically, it’s nonsense. A vague comment about human desire, in a sporadic

form. Just a melodic journey really. I liked the jazz changes in the middle; it

just rolls around an A major sequence. Pretty. When I first wrote it, I was

lucky enough to perform it with backing singers: the way they layer the ‘What

for?’ chorus section. I always thought

if I ever get the chance, that’s the way I’ll produce it. It was worth digging

that song out for you guys to sing on it.

WS: I don’t think

about it as lyrically fluffy. Or meaningless. Probably I’m not listening to it.

JW: Yeah. Reverential’s

a story, isn’t it? Best Friend’s a

story. You can tune into the lyric. Here it doesn’t matter. It’s just a melody

really.

WS: And it’s fun

playing double bass on it.

JW: Sonically and musically that was good getting you to

play double bass and bring that into the band.

WS: That’s why you

persuaded me to buy a double bass. About a year ago. Less than a year.

JW: Yeah. Musically we did it without a metronome, which is

unusual. Free time. I like the way it accelerates and decelerates.

GRATIFICATION

JW: Gratification was born of playing Reverential. Exactly

same tuning, same capo position. But more aggressive and strummy, still using

the same sort of chord pattern. A fret higher. Really like the riff.

The song is borne out of an argument with my wife, and being

annoyed. In analysing the argument, I sense that everyone wants to be right.

From that, I had this concept of gratification. We want to be gratified – in our

anger and in our rightness. Since writing it, I’ve realised the core of the

lyric is a trigger: we’re triggered into anger, from our childhood. It’s the

story of my childhood and not being gratified via my parents – in being called

names, in being taunted and not being able to reply, and sulking.

WS: And when you say

you’ve realised, that’s not from listening to the song? That’s just life?

JW: I don’t want to say it’s a song about my wife. It’s

realising that I’m having an argument with someone, and I’m just getting

triggered into my childhood reactions. And that’s what the song’s about, really,

is about those childhood, immature reactions and situations.

WS: I think that’s a

big thing in the world that we don’t understand – about ourselves.

JW: And that’s a nice thing about the song, if it has a positive

spin. To try and take ownership. And the very last line, ‘Why is it always that

critical voice? Is there something missing in our life?’ Asking that question,

how do we need to educate people, not just about maths and English

[WS witters on about

attachment disorder, and Gosport.]

JW: Yes, there’s a complete void of emotional education in

our system. For years and years in (a) my experience of school (I feel let down

by that) and (b) working in education, I see this huge void. As human beings,

we all have so much in common. It’s questionable how much trigonometry we’re

going to use, how much grammar. But when we’re going to be parents, to interact

with adults, to write a lot of emails, it’s exceptionally important to

understand who we are emotionally and how we arrived there and some of the

things we can do to understand it and maybe not disarm it, but to channel it.

It’s a source of you know… If religion is there to give a

moral code, then this is a 21st century replacement: understanding

ourselves to improve life for ourselves. And for our children.

AMBIGYOUUS

WS: I like the idea

that Gratification is a partner song for Reverential, but different. The lyric

of Reverential has counterparts in Therapist.

JW: OCD is the

brother of Therapist. Reverential is unfortunately about

anger, which is a path I’ve been down too many times – lyrically. I’m still

working through it. If writing a lyric is cathartic, saying I’m angry, I’m

pissed off, I’d rather write a lyric than put a chair through a window.

WS: We talked about

writing the same song. I worry about writing the same novel twice, with

different names. But our friend TB Layden who’s painting upstairs, Tim, you don’t

worry about painting the same picture, do you?

TBL: I get asked to do the same painting twice, because it’s

sold and someone else wanted it. And realising I couldn’t, making an attempt,

realising I couldn’t. I like to rework things, to take things and change them. Taking

that raw material, turning that raw material into a new thing I enjoy. I’m

incapable of reproducing something in the same way.

WS: Yes, but I’m

claiming variations on a theme is not only a good way to develop your skills

but is also satisfying for a viewer or reader. Classical musicians don’t fear

that. A lot of songwriters don’t fear that. We all have our domain. It’s okay

to obsess.

JW: I’m not afraid of it. I’m apologetic. Maybe harbouring

it, still owning it, trying to move forward… The actual name of this folder

is JAMIE 8 and it says in brackets (LOVE SONGS). The aim of this project was to

write love songs. Because it’s something I don’t do. I wanted to challenge

myself to see if I could do it. That was important in Reverential, to make that statement about that, to Lucy.

That was the only bit of the LOVE SONGS, the only bit of

content, that made it on there. Oh no, there is a bit in In the Shadows where it says ‘We still have each other’. I like

that. It’s an optimistic song. It’s about the underdog.

WS: It sounds dark,

but it’s … Love songs! I think that’s a great method. Give yourself a

challenge: do something else, by mistake or contrariness. That’s a good place

to end. What’s next?

JW: Going to think about launching it. Try and find a venue.

Going to speak to the band – which is you. Put a night on, like we did last

time, have everyone come. And maybe play the whole album in its entirety,

because after that it’ll never get done again. Not unless someone offers us a

lot of money.

Jamie’s website with songs and videos

JAMIE & THE JETS FACEBOOK

I’ll repost my article about Jamie’s band Lewd from 2004

and add links to songs as they become available.

Please Feel Free to Share: