Rachmaninoff Uncorked — Take Two: RCA, Ormandy, and the Cork

Charles O’Connell, who commanded “artists and repertoire” for RCA Victor from 1930 to 1944, left a book of reminiscences – The Other Side of the Record (1947) – documenting an astute, querulous intellect and a meddlesome ego. It was often O’Connell who decided what music famous conductors, pianists, and violinists might commercially record.

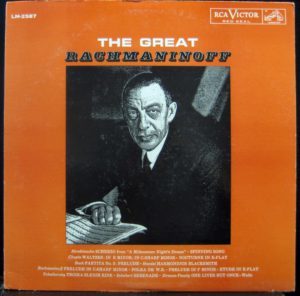

O’Connell admired Sergei Rachmaninoff – yet only recorded Rachmaninoff in two extended solo piano works: Schumann’s Carnaval and Chopin’s B-flat minor Sonata, both classics of the discography for piano. That is: O’Connell failed to record Rachmaninoff’s esteemed readings of Liszt’s Sonata or Beethoven’s Op. 111. Or of the piece Rachmaninoff considered his supreme compositional achievement: the existential Symphonic Dances. Rachmaninoff was known to play the Symphonic Dances, privately, with his friend Vladimir Horowitz in the two-piano version. We know that he wished to record the Symphonic Dances as a conductor. O’Connell had thrice recorded Rachmaninoff memorably conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra in his own music. But O’Connell lacked enthusiasm for the Symphonic Dances and nothing was done.

All this matters greatly because Rachmaninoff refused to allow his live performances to be broadcast or otherwise recorded. Even though he was a master of musical structure, we have no documentation whatsoever of how he shaped the monumental Beethoven and Liszt pieces he famously purveyed. As important: we don’t know what he sounded like in a real hall with a real audience.

The new Marston 3-CD set “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances” – the topic of my previous blog – permits a glimpse of this “real” Rachmaninoff: a supreme instrumentalist more emotionally aroused than the one O’Connell managed to capture in sound. Rachmaninoff’s private rendering of his Symphonic Dances, as recorded by Ormandy (probably without the pianist’s knowledge), is an unprecedented opportunity to eavesdrop on Rachmaninoff performing absent the intrusive self-awareness imposed by RCA’s microphones.

This historic release also suggests another impediment to hearing the real Rachmaninoff: Eugene Ormandy himself.

Of the repertoire Rachmaninoff happened to record, only one extended composition embeds the searing nostalgia that was the expressive keynote of this great artist. That is the Piano Concerto No. 3. His 1939-40 recording, with Ormandy, is a dry run. The concerto’s lachrymose intensity is missing.

That it did not have to be is proven by Rachmaninoff’s 1929 recording of a less emotionally fraught composition: the Piano Concerto No. 2. The difference is the conductor, Ormandy’s irreplaceable predecessor in Philadelphia: Leopold Stokowski.

Ormandy’s recorded accompaniments to Rachmaninoff’s First, Second, and Fourth Piano Concertos are merely supportive: they give the soloist nothing to work with. (My pianist friend George Vatchnadze, describing the Rachmaninoff-Ormandy relationship, calls Ormandy a “puppy” and a “servant” — apt adjectives.) Stokowski’s accompaniment to the Second Concerto is unique. The signature lava flow of his magnificent Philadelphia strings is not only memorably ravishing; it is acutely calibrated in dialogue with the composer/pianist. It is not for nothing that Rachmaninoff called Stokowski’s Philadelphia Orchestra the greatest orchestra that had ever existed.

If you want to hear what I’m talking about, listen first to the passage from the First Concerto that Vladimir Horowitz once identified as the only instance of RCA adequately conveying Rachmaninoff’s art. This is the piano solo beginning at 12:52 here. And observe how the intrusion of Ormandy’s generic accompaniment cancels the abandon of Rachmaninoff’s playing, with its untethered rubatos and magically layered dynamics.

Now Stokowski – try the coda to the first movement of the Second Concerto, beginning at 8:45 here. You’ll hear pianist and conductor immersed in an inspired dialogue: two exemplary instruments of musical expression – Stokowski’s orchestra and Rachmaninoff’s Steinway – feed one another.

It is hardly surprising that once Ormandy took over, Stokowski did not guest-conduct in Philadelphia for more than two decades. Or that Stokowski, when passing through Philadelphia by train, would invariably lower the window shade.

How is it possible that Eugene Ormandy could have succeeded Leopold Stokowski? Both O’Connell and Arthur Judson, classical music’s supreme powerbroker, played decisive roles (O’Connell, in his book, testifies that Ormandy looked upon Judson “as on a father”). This choice — coinciding with refugee conductors of world stature looking for work in the US (Kleiber, Klemperer, etc.) — is one of the most parochial blunders in the institutional history of classical music in America. It bears comparison with the Met’s decision to replace Artur Bodanzky with Erich Leinsdorf in 1939; Leinsdorf, too, was a refugee — but no Kleiber or Klemperer. Two decades later, RCA inflicted Leinsdorf on the Boston Symphony; the resulting recordings are today forgotten.

And how is it possible that Rachmaninoff chose to record with Ormandy? According to O’Connell, “he preferred Ormandy to anyone, though he collaborated successfully and in the most friendly fashion with Stokowski.”

But O’Connell held Ormandy in exaggerated esteem. And I read in Richard Taruskin’s copious note for the new Marston release that Rachmaninoff, his longtime loyalty to Philadelphia notwithstanding, didn’t care for Ormandy’s reading of the Symphonic Dances — his preferred conductor for that work (other than himself) being Dmitri Mitopoulos. The Marston set includes a scorching New York Philharmonic Symphonic Dances led by Mitropoulos in live performance in 1942.

Another annotation for the new Marston release, by the producers, reports that Rachmaninoff’s preferred interpreters included Stokowski, Mitropoulos, and Willem Mengelberg – an informative list. These were sui generis conductors who never played by the rules. And, however constrained he may have been in the presence of Charles O’Connell and Eugene Ormandy – neither did Sergei Rachmaninoff.

PS: In an email exchange with Gregor Benko, the longtime Rachmaninoff authority who co-produced “Rachmaninoff Plays Symphonic Dances,” I learned the following:

“O’Connell tried to kill two birds with one stone, thinking he would please Rachmaninoff in keeping his promise for Victor to record Symphonic Dances, and satisfying his annual contractual commitment to Frederick Stock and the Chicago Symphony, by having Stock make the recording. He hadn’t realized how much this would displease Rachmaninoff, or how much Rachmaninoff wanted to conduct the recording himself. As happens so regularly at record companies, this seemingly minor personality kertuffle resulted in total failure, and no one recorded the Dances. O’Connell claimed that Rachmaninoff forgave him later, but we believe that is not true.

“As for plans for recording the Symphonic Dances with Vladimir Horowitz [in the two-piano version]: talk of this has been much exaggerated, based on wishful thinking. Horowitz and Rachmaninoff played it together privately in California, unknown date but sometime after their first two piano partying there in June, 1942. Rachmaninoff was already ill and his circle was very worried. He tried to keep up a good face, and went with Horowitz to see Bambi at the Disney studios. On July 17 & 18 Rachmaninoff played in the Hollywood Bowl and he was bent over. Lumbago, it was explained, but it was probably acute pain. In July Steinway stopped making pianos as the war really began affecting music. A few weeks later his cancer was diagnosed. It was a struggle just to fulfill contracted engagements for late 1942/early 1943, and plans for the future were on hold. No contracts for new things, no dates set aside for new recordings. Each contracted concert played was a trial, and finally in mid-February he stopped the tour. He died at the end of March. There was no way such a recording could have happened . . . ”

For much more on Arthur Judson and Leopold Stokowski, see my “Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall” (2005). For more on Charles O’Connell, David Sarnoff, the provincial NBC/RCA impact on American musical life, see my once notorious “Understanding Toscanini: How He Became an American-Culture God and Helped Create a New Audience for Old Music “[1987].)

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers