Proof of the Existence of God from The Realist Guide

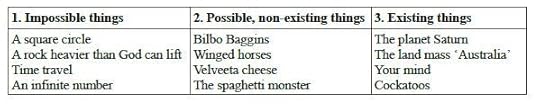

There could not possibly be any reality whatsoever if there were no first cause of existence, if there were no God. Consider the table below:

In the far left column are things the very notion of which implies a contradiction, like the phrase ‘uncreated creatures.’ Since the mode of being of a square, for instance, excludes the possibility of it being a circle at the same time, if, per impossibile, it did exist, then it would also not exist. It would be a square, in that it realised squareness, and it would not be a square, in that it did not realise squareness, as it was a circle. Even if we were to assign a name to square circle, such as ‘squircle’, we could not form a single concept matching up with that name, because the mind is something real, and just as no real being can exist and not exist at once and in the same respect, so also no mind can both think and unthink, attribute and not attribute, delimit and unlimit an idea at once. For such would be required to form a single idea ‘square unsquare’. All of this offends the principle of non-contradiction, which must be held to rigorously if one wishes to use the intellect at all. As realists, we hold to the reliability of the intellect and so to its first principles.

In the middle column, we have beings which are the fruit of human imagination, but have not been endowed with extramental reality. What is lacking to them? An act of existence, an act to make them stand outside of nothing. What is privy to them? An image, an idea, something philosophers call ‘logical being’.

The question that comes to our mind when considering the poor unfortunates in the middle column is: Why don’t they exist? They could exist, but they have nothing of real being. Why didn’t J.R.R. Tolkien and why doesn’t Peter Jackson instantiate some real live hobbits for us, so that we can have a Shire on Earth?

Those asking such questions are illustrating Aquinas’ proof for the real distinction between essence and existence propounded in chapter 4 of his De Ente et Essentia.i We all know that just because an idea or form or essence of some thing can be conceived, that does not mean that the thing actually exists. For it to do so, another component is required: the act of existence.

No literary author in the history of the world—Tolkien included—has ever provided his character with real existence, though Chesterton wrote a play, The Surprise, about a playwright with such power, and Pirandello a play about Six Characters in Search of an Author. The fact is that no human has power over existence qua existence, the ability to make real that which has nothing of being, that supreme omnipotence that has a power without limits because it is the very source of limits in the thing it creates.

And so, when we come to the third column, the column of things that are real, we see that there must be some reason why they are so, that is, why they are something rather than nothing, in Leibniz’s words. If there wasn’t a need for an extra cause to move from column 2 to column 3, then we would have to say that there is no difference between existing and not existing, which is surely not the case! Those in column 2 have essence without existence, while those in column 3 have both. And so the cause that bridges the appalling gap between the two is one that accounts for existence, that is, the very fabric of reality as such. This cause we commonly called God.

God, then, is the first cause of all existing things, and He provides a sufficient reason for there being a reality. His role is not of a single moment, but of every moment. He holds the universe ‘between His index finger and thumb’, such that, letting it go, it would fall into nothingness. Thus, even if the universe

were entirely without end or beginning, there would still be exactly the same logical need of a Creator. Anybody who does not see that … does not really understand what is meant by a Creator.ii

It may be fashionable to deny God’s existence, but to do so is to remove from reality its own basis of intelligibility. The reason is as follows:

1. That which constitutes reality and makes it knowable is ‘being.’

2. ‘Being’ that does not exist of itself must have its source in some ‘existence maker.’

3. All beings within our common experience are beings that do not exist of themselves, and so must necessarily rely on an ‘existence maker.’

4. Therefore, one who denies that there is an ‘existence maker’ is unable to explain why there are beings at all.

5. One who cannot explain why there are beings at all is not in a position to make coherent use of the word corresponding to ‘being’, the word ‘is.’ He will speak the word ‘is’ while refusing to acknowledge that its notion has a foundation for its reality and so its intelligibility.

Logically, then, to deny the existence of God is to take away the causal basis for the ‘is’ which we conceptualise from the world around us. How much safer it is for rational discourse and epistemological health to accept the data of sense telling us things are limited, and the intellect inferring from hence that they have their source in something unlimited.

(This is an excerpt from The Realist Guide to Religion and Science, pp. 50–53)

i For a full-blown defence of Aquinas’s thesis, see Feser, Scholastic Metaphysics, section 4.2.1.

ii G. K. Chesterton, St. Thomas Aquinas (London: Hodder & Stoughton Limited, 1933), p. 206.