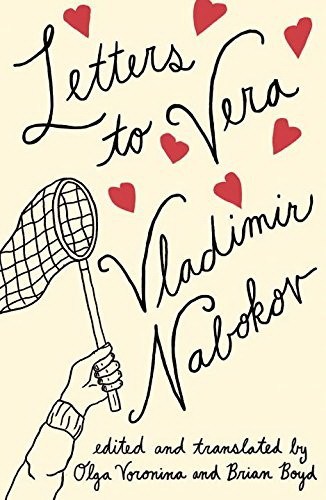

Letters to Vera by Vladimir Nabokov

This review originally appeared in The Sunday Business Post in October 2014.

*

Vladimir Nabokov – the Cambridge-educated son of Russian aristocrats displaced by the Bolshevik Revolution; the author of glittering, gamesome books about savage subjects; the hard-up lepidopterist who spent his retirement in a suite of rooms on the sixth floor of the west wing of the Montreux Palace Hotel in Switzerland – seems an almost preposterously unlikely figure. He seems, in fact, to be a character from one of his own novels: remote, imposingly learned, glacially condescending.

Martin Amis once remarked upon the “novelettish glamour” of Nabokov’s life. And the life of the author of Lolita is almost indecently good fun to read about. He was a child prodigy, chatting away in English, French and Russian in the nursery of his family’s estate (“I was a perfectly normal trilingual child in a family with a large library”). As an adolescent he wrote lyric verse of astonishing maturity. In the 1920s, when Berlin became a centre of Russian émigré life, Nabokov established himself as one of the central writers of the emigration, publishing his first novels under the pen-name V. Sirin. These novels – long since translated into English, and including the extraordinary black comedies King, Queen, Knave (1928) and Laughter in the Dark (1933) – now open a window to that vanished world: a world of cultured Russians suffering the agonies of genteel poverty and exile. The Berlin of Nabokov’s early novels is long gone – it was one of the earliest casualties of the Second World War. But it lives on in the pages of books like Despair (1934), a vivid and antic precursor to Lolita (1959).

It was in Berlin that Nabokov first met Vera Evseevna Slonim, the woman who was to become his wife. Vera’s father ran a small publishing firm, and approached Nabokov with the idea of translating Dostoyevsky into English. The project came to nothing, but at a charity ball on the 8th or 9th of May 1923 (biographers disagree about the date), Nabokov was introduced to Vera. It seems to have been love at first sight, or something very near. Vera wore a mask that she refused to take off – which is, of course, the sort of thing that might happen in a novel of Nabokov’s. (This is what amazes you, as you read about Nabokov’s life: the sheer frequency with which incredibly Nabokovian things kept happening to him.) Though of course, in a Nabokov novel, the woman beneath the mask would turn out to be a vain and boorish coquette. And Vera was neither of these things. She, too, was literary: she knew Nabokov’s poetry and had heard him read. Vladimir was 24; Vera 21. They were married two years later.

“And there,” wrote Martin Amis in 1981, when Vladimir was dead and Vera in her eighth decade, “the visible story ends.” By which he meant that there was no way of seeing into the private recesses of the Nabokovs’ marriage. With the publication of this hefty volume of correspondence, this is no longer the case. Reading the letters a writer composes for his partner’s eyes can be a queasy business: who can forget their first encounter with the scatological fantasies that James Joyce sent to Nora Barnacle? Very properly, while the principals are still alive (or cushioned by the lingering respect of living memory), we regard the inner workings of a marriage as none of our business. But time and prurience have a way of eroding propriety. So here – handsomely accoutred with prefatory matter, and exhaustively annotated – are the letters that Vladimir sent to Vera, whenever they were apart, over the five decades of their love.

The first was sent soon after their encounter at the masquerade ball. Plainly Vladimir had been struck by a lightning bolt: “I won’t hide it: I’m so unused to being – well, understood, perhaps, that in the very first minutes of our meeting I thought: this is a joke, a masquerade trick… I need you, my fairy-tale. Because you are the only one I can talk with about the shade of a cloud, about the song of a thought.” If Nabokov’s character was an admixture of the romantic and the sinister, then it is the romantic Vladimir who predominates in these pages. The letters are full of lyrical flashes and flights of fancy: “Angels themselves smoke – in their sleeves. But when the archangel goes by, they throw their cigarettes away: this is what falling stars are.”

With the exception of Vladimir’s single adulterous affair – with a young woman who worked as a dog-groomer, another seamlessly Nabokovian detail – Vladimir and Vera enjoyed a cloudless marriage. The letters collected here testify to a shared lifetime of openness and generosity. Those looking for dirty secrets will be disappointed; but anyone in search of yet another reason to admire Vladimir Nabokov will be hugely rewarded.

Kevin Power's Blog

- Kevin Power's profile

- 29 followers