Using Settings to Tap Your Reader's Imagination

by Jan Drexler

In my June post, I talked about giving your readers a complete story experience by immersing them in your fictional world. We discussed how to make that world come alive for you, the writer. You can read that post here.

Today we’re going to take your story world a step further: how to convey what you see in your mind onto the page and into your reader’s imagination.

Because, really, isn’t that the where the magic of story-telling happens?

We use the setting of each scene to convey emotion and increase our reader’s perception of our themes. Every word reveals details about the scene that provides an undercurrent to strengthen the action and dialogue. Many writers talk about using your setting as another character in the scene, but I think it goes further than that.

Yes, your characters interact with the setting, but the setting also creates a framework that helps to communicate your theme and subtexts more effectively than any other aspect of your story.

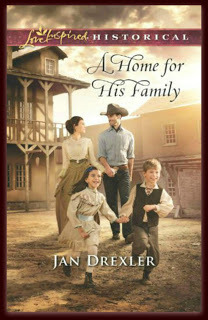

To help illustrate what I’m talking about, I’m going to use some scenes from one of my early books, A Home for His Family, published by Love Inspired in September 2015.

The opening scene of the book takes place in a gulch outside of Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in 1877. Yup, that’s right. Just like in a Hopalong Cassidy story. It’s May, there’s a snowstorm coming, and it’s one of only three roads into town. The spring influx of miners is arriving, and the place is a chaotic mess.

The heroine, Sarah, and her Aunt Margaret have been traveling to Deadwood in a stagecoach and are anxious to get to the end of their journey. But there is a delay ahead of them on the trail and the stagecoach is stuck until traffic starts moving again.

Deadwood, South Dakota

Deadwood, South Dakota

Here is Sarah’s first glimpse of the setting:

Sarah climbed out of the stagecoach, aching for a deep breath. With a cough, she changed her mind. The air reeked of dung and smoke in this narrow valley. She held her handkerchief to her nose and coughed again. Thick with fog, the canyon rang with the crack of whips from the bull train strung out on the half-frozen trail ahead. She pulled her shawl closer around her shoulders and shook one boot, but the mud clung like gumbo.

In describing this scene, I wanted to show the unexpected hardships Sarah was facing in her new adventure, but also her determination to follow through with her plans. So I let her leave the stagecoach to get some fresh air, but then she comes nose-to-nose with reality. The weather creates an oppressive layer of fog that obscures her vision and concentrates the odors of hundreds of animals and men confined in a narrow space.

There’s a subtext going on in this description, too. Sarah has come to Deadwood to bring the light of education to the children in the town and to the prostitutes who make up a significant number of the female population in 1877. A recurring theme in the story is that the prostitutes are trapped and confined in their lives with little hope for escape. The narrow gulch in this first scene is the reader’s – and Sarah’s – first hint of that unsavory reality.

This isn’t the only place I use the setting to convey that subtext. I scatter it throughout the story:

This cabin and a few others were perched on the rimrock above the mining camp, as if at the edge of a cesspool. Up here the sun was just lifting over the tops of the eastern mountains, while the mining camp below was still shrouded in pre-dawn darkness.

* * * * *

The businesses crowded together between the hills rising behind them and the narrow mud hole that passed for a street. Nate slowed his pace as the storefronts turned from the saloons to a printing office. Next came a general store and a clothing store, with a tobacconist wedged in between. Across the street was Star and Bullock, a large hardware store that filled almost an entire block.

And in the middle of it all, just where the street took a steep slope up to a higher level on the hill, men worked a mining claim. Nate shook his head. In all his travels through the West, he had never seen anything quite like Deadwood.

But even amid the chaos of the mining town, Sarah’s spirit is focused on her goals. I use descriptions like this one to show Sarah’s hopeful courage:

Sarah took the bucket to the door and tossed the dirty water into the gutter. As she did every day, she looked past the crowded streets and crooked roofs of the neighboring buildings to the towering hills beyond. She let the bucket dangle and leaned against the door frame as she gazed at the white rocks at the top of Boot Hill. What would it be like to climb that mountain someday?

Deadwood from White Rocks

Deadwood from White Rocks

Another aspect of any story is contrast. In this story it is between chaos and order; sin and forgiveness; the wandering life and home.

How can you convey the contrasts in your story? Choose your words carefully.

Yesterday's rain had made a miry mess of the streets. Horses walked in mud nearly up to their knees, while the drivers of the wagons shouted curses to keep their teams from stopping before they got to firmer ground.

Sarah crossed Lee Street on the wooden crosswalk and paused on the corner, looking up and down Main. Aunt Margaret had been right. The saloon girls crowded the board walks in front of the stores, their bright silk dresses and fancy plumed hats lining the street like a show of exotic tropical flowers. Not one “respectable” woman was in sight.

Finally, she caught sight of Maude’s red dress and purple shawl in a cluster of girls outside a peanut vendor next to The Big Horn Grocery on Upper Main. She hurried across the street on the wooden walk, soaking her kid shoes in the slime as the boards sank into the mud beneath the weight of the crowd doing the same. Thankfully, she climbed the stairs between Lower and Upper Main, out of the mud for a change.

Compare that to Nate observing Sarah’s first view of the land where he intends to establish his home:

He drove the team along a natural shelf on the side of the slope and then turned up. As they crested the rise, the sight that greeted him still took his breath away.

Green meadows stretched away in a wide swath at least a half mile across and twice that long, curving around the wooded slopes that crowded close to the open space. An eagle drifted above them against the clear blue sky.

Sarah whispered, “It’s perfect.”

Nate chirruped to the horses, driving them slowly through the knee-deep grass, heading for the grove of trees at the far edge. In his mind the mountain valley was dotted with horses—brown, black, white, gray—all grazing on the rich green grass that grew in a thick carpet everywhere he looked. Across the meadow, a meandering line of cottonwood trees followed a fold in the grass. That stream cutting through the land was the crowning touch.

He glanced at Sarah, still standing in the wagon bed, holding on to the seat between him and James. Her face was bright in the clear sunshine, the wind pulling loose hair from her bun. Her gaze went up to the tops of the hills surrounding them.

When she looked at him she smiled, and his heart swelled. Everywhere he looked he saw his future, waiting for him to reach out and grasp it. It was as if the past twelve years had never happened and he was just starting out, full of promise.

What is the biggest difference between these two scenes? It isn’t only the contrast between the crowded streets of Deadwood and the open spaciousness of Nate’s land.

In the description of the town, I used a lot of words with hard consonants: curses, crosswalk, corner, crowded, walk, silk, exotic, respectable, kid…along with some “dirty” words for good measure: mud, mess, soaking, slime, sank.

But in the description of Nate’s land? The opposite. I used soft consonants and “clean” words: green meadows, meandering, wide swath, curving around, wooded slopes, drifted, clear blue sky, swelled, full of promise.

Words are important – not only their meanings, but their sounds. The soft consonants convey the underlying theme present in all my books: home.

Do my readers notice these details? Not consciously. But they play a role in the total reading experience.

Now I’d love to hear your ideas. How do you use your settings to add depth to your stories? Or for readers, how do carefully written settings add to your reading experience?

"A Home for His Family" is now out of print, but the e-book is still available! One commenter will win a Kindle copy of their very own!

The Rancher's Ready-Made Family

The Rancher's Ready-Made Family

Nate Colby came to the Dakota Territory to start over, not to look for a wife. He'll raise his orphaned nieces and nephew on his own, even if pretty schoolteacher Sarah MacFarland's help is a blessing. But Nate resists getting too close—Sarah deserves better than a man who only brings trouble to those around him.

Sarah can't deny she cares for the children, but she can't let herself fall for Nate. Her childhood as an orphan taught her that opening her heart to love only ends in hurt. Yet helping this ready-made family set up their ranch only makes her long to be a part of it—whatever the risk.

Order your copy here!

Jan Drexler lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota with her husband of (almost) thirty-six years and expanding family. While she writes Historical Romance with Amish characters, the romance of cowboys surrounds her, tugging more story ideas from her imagination than she can hope to write in one lifetime.

Jan Drexler lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota with her husband of (almost) thirty-six years and expanding family. While she writes Historical Romance with Amish characters, the romance of cowboys surrounds her, tugging more story ideas from her imagination than she can hope to write in one lifetime.

In my June post, I talked about giving your readers a complete story experience by immersing them in your fictional world. We discussed how to make that world come alive for you, the writer. You can read that post here.

Today we’re going to take your story world a step further: how to convey what you see in your mind onto the page and into your reader’s imagination.

Because, really, isn’t that the where the magic of story-telling happens?

We use the setting of each scene to convey emotion and increase our reader’s perception of our themes. Every word reveals details about the scene that provides an undercurrent to strengthen the action and dialogue. Many writers talk about using your setting as another character in the scene, but I think it goes further than that.

Yes, your characters interact with the setting, but the setting also creates a framework that helps to communicate your theme and subtexts more effectively than any other aspect of your story.

To help illustrate what I’m talking about, I’m going to use some scenes from one of my early books, A Home for His Family, published by Love Inspired in September 2015.

The opening scene of the book takes place in a gulch outside of Deadwood, Dakota Territory, in 1877. Yup, that’s right. Just like in a Hopalong Cassidy story. It’s May, there’s a snowstorm coming, and it’s one of only three roads into town. The spring influx of miners is arriving, and the place is a chaotic mess.

The heroine, Sarah, and her Aunt Margaret have been traveling to Deadwood in a stagecoach and are anxious to get to the end of their journey. But there is a delay ahead of them on the trail and the stagecoach is stuck until traffic starts moving again.

Deadwood, South Dakota

Deadwood, South DakotaHere is Sarah’s first glimpse of the setting:

Sarah climbed out of the stagecoach, aching for a deep breath. With a cough, she changed her mind. The air reeked of dung and smoke in this narrow valley. She held her handkerchief to her nose and coughed again. Thick with fog, the canyon rang with the crack of whips from the bull train strung out on the half-frozen trail ahead. She pulled her shawl closer around her shoulders and shook one boot, but the mud clung like gumbo.

In describing this scene, I wanted to show the unexpected hardships Sarah was facing in her new adventure, but also her determination to follow through with her plans. So I let her leave the stagecoach to get some fresh air, but then she comes nose-to-nose with reality. The weather creates an oppressive layer of fog that obscures her vision and concentrates the odors of hundreds of animals and men confined in a narrow space.

There’s a subtext going on in this description, too. Sarah has come to Deadwood to bring the light of education to the children in the town and to the prostitutes who make up a significant number of the female population in 1877. A recurring theme in the story is that the prostitutes are trapped and confined in their lives with little hope for escape. The narrow gulch in this first scene is the reader’s – and Sarah’s – first hint of that unsavory reality.

This isn’t the only place I use the setting to convey that subtext. I scatter it throughout the story:

This cabin and a few others were perched on the rimrock above the mining camp, as if at the edge of a cesspool. Up here the sun was just lifting over the tops of the eastern mountains, while the mining camp below was still shrouded in pre-dawn darkness.

* * * * *

The businesses crowded together between the hills rising behind them and the narrow mud hole that passed for a street. Nate slowed his pace as the storefronts turned from the saloons to a printing office. Next came a general store and a clothing store, with a tobacconist wedged in between. Across the street was Star and Bullock, a large hardware store that filled almost an entire block.

And in the middle of it all, just where the street took a steep slope up to a higher level on the hill, men worked a mining claim. Nate shook his head. In all his travels through the West, he had never seen anything quite like Deadwood.

But even amid the chaos of the mining town, Sarah’s spirit is focused on her goals. I use descriptions like this one to show Sarah’s hopeful courage:

Sarah took the bucket to the door and tossed the dirty water into the gutter. As she did every day, she looked past the crowded streets and crooked roofs of the neighboring buildings to the towering hills beyond. She let the bucket dangle and leaned against the door frame as she gazed at the white rocks at the top of Boot Hill. What would it be like to climb that mountain someday?

Deadwood from White Rocks

Deadwood from White RocksAnother aspect of any story is contrast. In this story it is between chaos and order; sin and forgiveness; the wandering life and home.

How can you convey the contrasts in your story? Choose your words carefully.

Yesterday's rain had made a miry mess of the streets. Horses walked in mud nearly up to their knees, while the drivers of the wagons shouted curses to keep their teams from stopping before they got to firmer ground.

Sarah crossed Lee Street on the wooden crosswalk and paused on the corner, looking up and down Main. Aunt Margaret had been right. The saloon girls crowded the board walks in front of the stores, their bright silk dresses and fancy plumed hats lining the street like a show of exotic tropical flowers. Not one “respectable” woman was in sight.

Finally, she caught sight of Maude’s red dress and purple shawl in a cluster of girls outside a peanut vendor next to The Big Horn Grocery on Upper Main. She hurried across the street on the wooden walk, soaking her kid shoes in the slime as the boards sank into the mud beneath the weight of the crowd doing the same. Thankfully, she climbed the stairs between Lower and Upper Main, out of the mud for a change.

Compare that to Nate observing Sarah’s first view of the land where he intends to establish his home:

He drove the team along a natural shelf on the side of the slope and then turned up. As they crested the rise, the sight that greeted him still took his breath away.

Green meadows stretched away in a wide swath at least a half mile across and twice that long, curving around the wooded slopes that crowded close to the open space. An eagle drifted above them against the clear blue sky.

Sarah whispered, “It’s perfect.”

Nate chirruped to the horses, driving them slowly through the knee-deep grass, heading for the grove of trees at the far edge. In his mind the mountain valley was dotted with horses—brown, black, white, gray—all grazing on the rich green grass that grew in a thick carpet everywhere he looked. Across the meadow, a meandering line of cottonwood trees followed a fold in the grass. That stream cutting through the land was the crowning touch.

He glanced at Sarah, still standing in the wagon bed, holding on to the seat between him and James. Her face was bright in the clear sunshine, the wind pulling loose hair from her bun. Her gaze went up to the tops of the hills surrounding them.

When she looked at him she smiled, and his heart swelled. Everywhere he looked he saw his future, waiting for him to reach out and grasp it. It was as if the past twelve years had never happened and he was just starting out, full of promise.

What is the biggest difference between these two scenes? It isn’t only the contrast between the crowded streets of Deadwood and the open spaciousness of Nate’s land.

In the description of the town, I used a lot of words with hard consonants: curses, crosswalk, corner, crowded, walk, silk, exotic, respectable, kid…along with some “dirty” words for good measure: mud, mess, soaking, slime, sank.

But in the description of Nate’s land? The opposite. I used soft consonants and “clean” words: green meadows, meandering, wide swath, curving around, wooded slopes, drifted, clear blue sky, swelled, full of promise.

Words are important – not only their meanings, but their sounds. The soft consonants convey the underlying theme present in all my books: home.

Do my readers notice these details? Not consciously. But they play a role in the total reading experience.

Now I’d love to hear your ideas. How do you use your settings to add depth to your stories? Or for readers, how do carefully written settings add to your reading experience?

"A Home for His Family" is now out of print, but the e-book is still available! One commenter will win a Kindle copy of their very own!

The Rancher's Ready-Made Family

The Rancher's Ready-Made Family

Nate Colby came to the Dakota Territory to start over, not to look for a wife. He'll raise his orphaned nieces and nephew on his own, even if pretty schoolteacher Sarah MacFarland's help is a blessing. But Nate resists getting too close—Sarah deserves better than a man who only brings trouble to those around him.

Sarah can't deny she cares for the children, but she can't let herself fall for Nate. Her childhood as an orphan taught her that opening her heart to love only ends in hurt. Yet helping this ready-made family set up their ranch only makes her long to be a part of it—whatever the risk.

Order your copy here!

Jan Drexler lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota with her husband of (almost) thirty-six years and expanding family. While she writes Historical Romance with Amish characters, the romance of cowboys surrounds her, tugging more story ideas from her imagination than she can hope to write in one lifetime.

Jan Drexler lives in the Black Hills of South Dakota with her husband of (almost) thirty-six years and expanding family. While she writes Historical Romance with Amish characters, the romance of cowboys surrounds her, tugging more story ideas from her imagination than she can hope to write in one lifetime.

Published on July 15, 2018 21:00

No comments have been added yet.