trust is earned

It’s been two weeks but I’m still thinking about my experience at the SWaG conference. The auditorium where I delivered my keynote—“SAY HER NAME: Respect, Resistance, and the Representation of Black Girls”—was more of an amphitheater. I stood at ground level and ringed above and around me were about 75 educators; behind me was the screen with photos of Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and executive director of the African American Policy Forum (which launched the in 2015), and the three founders of the Black Lives Matter movement: Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. Midway through my talk I introduced quotes from members of the Black Girls’ Literacies Collective (BGLC), but I couldn’t use all the material I culled from the special issue of the NCTE journal English Education. I finished reading Ghost Boys last week and thought I would frame my discussion of the MG novel with a few pearls from three of the five members of the BGLC.

It’s been two weeks but I’m still thinking about my experience at the SWaG conference. The auditorium where I delivered my keynote—“SAY HER NAME: Respect, Resistance, and the Representation of Black Girls”—was more of an amphitheater. I stood at ground level and ringed above and around me were about 75 educators; behind me was the screen with photos of Kimberlé Crenshaw, legal scholar and executive director of the African American Policy Forum (which launched the in 2015), and the three founders of the Black Lives Matter movement: Patrisse Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. Midway through my talk I introduced quotes from members of the Black Girls’ Literacies Collective (BGLC), but I couldn’t use all the material I culled from the special issue of the NCTE journal English Education. I finished reading Ghost Boys last week and thought I would frame my discussion of the MG novel with a few pearls from three of the five members of the BGLC.

So—what are these scholars talking about when they suggest there’s something distinctive about Black girls’ relationship to literacy? In “Centering Black Girls’ Literacies: a Review of Literature on the Multiple Ways of Knowing of Black Girls,” Gholnecsar E. Muhammad and Marcelle Haddix explain it this way:

First…Black girls can know; simply stated, they have a voice. Black girls are generators and producers of knowledge, but this knowledge has been historically silenced by a dominant, White patriarchal discourse. Second…Black girls exhibit philosophies and practices that are distinguished from those of other groups. Third, Black girls represent two marginalized groups based on race and gender; however, this location cannot be simplified or generalized. The study of and with Black girls is complex…an intersectional lens is required to understand the literacy experiences of Black girls. (304)

Why should we care about how Black girls understand, engage with, and produce narratives? According to Muhammed and Haddix, “if we reimagine an English education where Black girls matter, all children would benefit from a curricular and pedagogical infrastructure that values humanity” (329). This quote immediately brought to mind a line from the Combahee River Collective’s 1977 “Statement:” “If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.”

In “Why Black Girls’ Literacies Matter: New Literacies for a New Era,” Yolanda Sealey-Ruiz argues that “restructuring the way we engage with Black girls in our classrooms, and maintaining accountability—as teachers and as members of school communities—is essential for their success” (294). Although Sealey-Ruiz is primarily addressing English educators, her recommendations have broader applications; as an author who writes for kids and teens, I certainly think of myself as a member of school communities, and feel I should also be held accountable for my professional practices. Just as English education can become “a site of possibility and disruption,” so can the production, assessment, and distribution of books for young readers. The kid lit community has the capacity to serve as a “space for resistance and for the educational excellence of Black girls” (295). Sealey-Ruiz contends that “we have the power to change the way Black girls are talked about” by “investigating their reality” and carefully considering the texts used in the classroom (295).

Blacks girls know from an early age just how they’re talked about in our society. Sealey-Ruiz opens her essay with a statement composed by four Black female high school students from the Bronx; the young women note that online, Black girls are routinely objectified and shamefully reduced to “their mere parts” (291). Haddix and Muhammad cite another study where “researchers found that eight Black adolescent girls (ages 12-17) felt that the media portrays Black girls as being judged by their hair; seen as angry, loud, and violent; and sexualized” (321). So what happens when this misrepresentation of Black girls is perpetuated instead of being refuted by Black authors?

Sealey-Ruiz cites a Facebook post by education researcher Monique Lane who contends that the lack of outrage around, and mobilization against, violence targeting Black girls in schools “encourages young Black girls to trust no one. It reminds us that we cannot count on other folks to have our backs. Not our peers. And sadly, not even our teachers” (292). Lane was writing in response to the 2015 assault against a Black female student at Spring Valley High School. But it made me wonder how Black girls perceive members of the kid lit community. Do they believe we have Black girls’ backs? When it comes to books for young readers, who can be trusted to put the interests of Black girls first when Black women make up just 0.01% of YA authors in the US and the publishing industry is dominated by White women?

WASHINGTON, DC – MARCH 24: Eleven-year-old Naomi Wadler addresses the March for Our Lives rally on March 24, 2018 in Washington, DC. Hundreds of thousands of demonstrators, including students, teachers and parents gathered in Washington for the anti-gun violence rally organized by survivors of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on February 14 that left 17 dead. More than 800 related events are taking place around the world to call for legislative action to address school safety and gun violence. (Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

Trust is earned. When considering Black girls’ relationship to stories, Sealey-Ruiz reminds us that “attention to their humanity is vital” (291). The African American Policy Forum is helmed by a Black woman. The Black Lives Matter movement was founded by three Black women. At the March for Our Lives, 11-year-old Naomi Wadler demonstrated #BlackGirlBrilliance when she gave an impassioned speech about violence against Black women and girls. Why are these powerful Black female activists not represented in novels for young readers that address police violence against the Black community? And why isn’t this erasure apparent and/or important to so many editors, reviewers, and readers?

I’ve got dozens of quotes from Ghost Boys that I’d like to explore, but ALA is this weekend so my review will have to wait. Right now I’m thinking perhaps what’s needed are some guidelines to help readers assess the representation of Black girls in books for young readers. In “Imagining New Hopescapes: Expanding Black Girls’ Windows and Mirrors,” SR Toliver reflects on Rudine Sims Bishop’s metaphor and points out the favored narratives that limit our ability to recognize the fullness of Black girlhood:

…the mirrors of Black girlhood are narrowed because they exclude Black girls from across the African Diaspora, confine Black girls to certain geographical regions, and limit the representation of older adolescents to stories centered around harsh, urban existences. The findings also suggest that the windows into Black girlhood are opaque because the exclusion of multiple representations of Black girlhood creates a slender opening through which to view the intricate and complex experiences of Black girls.

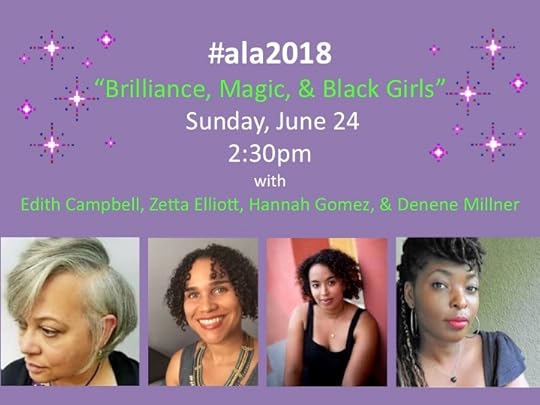

For our panel on Sunday we’ve put together a list of sixty books that demonstrate and celebrate the ingenuity, creativity, courage, and excellence of Black girls and women. But sixty books—or even a thousand—can’t fully represent the varied experiences of Black girls. I think it’s time we turned more Black girls into writers—published authors—so they can tell their stories themselves…