Trust in Science

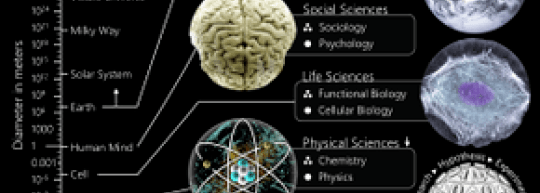

The scale of the universe mapped to branches of science.

“What makes people distrust science? Surprisingly, not politics” is an insightful piece recently penned in Aeon magazine by psychology professor Bastiaan T Rutjens.

Let mes start by saying that today’s distrust of science is astonishing when you consider that every single moment of your life you benefit from science. From the clean water your drink to the sewer systems that remove waste, from the marvels of modern medicine to wonders of technology, from the bridges you cross to the building you live in, from the phones and TVs you watch to the cars and planes you travel in, all result from the success of science. Half the people reading this post would have died of childhood diseases had they been born just a few generations ago. Before modern science, and the technology that results from it, life was indeed nasty, brutish, and short. Why then is there so much distrust of science?

The article begins by exploring a tentative answer—political ideology must be the culprit.

The sociologist Gordon Gauchat has shown that political conservatives in the United States have become more distrusting of science, a trend that started in the 1970s. And a swath of recent research conducted by social and political psychologists has consistently shown that climate-change skepticism in particular is typically found among those on the conservative side of the political spectrum.

However, research by the cognitive scientist Stephan Lewandowsky, as well as research led by the psychologist Sydney Scott, finds no relationship between political ideology and attitudes toward genetic modification and vaccine skepticism. So there must be more to science skepticism than mere political ideology. But what? To answer this question Rutjens and his colleagues recently published multiple studies that investigated both trust and skepticism of science. What they found were

four major predictors of science acceptance and science skepticism: political ideology; religiosity; morality; and knowledge about science. These variables tend to intercorrelate—in some cases quite strongly—which means that they are potentially confounded. To illustrate, an observed relation between political conservatism and trust in science might in reality be caused by another variable, for example religiosity.

Rutjens and his colleagues found that:

a) climate change skepticism was most pronounced among the politically conservative;

b) skepticism about genetic modification wasn’t related to political ideology or religious beliefs, but correlates highly with science knowledge—the more you know about science the less skeptical you are about the safety of, for example, genetically modified food;

c) vaccine skepticism also had no relation to political ideology but was strongest among religious participants and those with moral concerns about the naturalness of vaccination.

As for general trust in science and the desire for more funding for scientific research, the results were clear: it is by far lowest among the religious. The religiously orthodox have the most negative views of science and don’t want to invest federal money in science.

To summarize the findings Rutjens writes that, with the exception of climate-change skepticism, distrust in science isn’t driven by political ideology. Moreover, with the exception of the case of genetic modification, scientific literacy doesn’t seem to remedy distrust in science. Finally, regarding vaccine skepticism and distrust of science, religiosity plays the largest role.

Brief Reflection – I would also propose that poor education combined with our many cognitive biases and bugs undermined trust in science which is both the best way we have to uncover the truth about the world and the only cognitive authority in the world today. Here’s to hoping that we don’t revisit The Demon Haunted World[image error] that Carl Sagan wrote about so movingly.