Palmer Journal: II—Origin Story Pt. 2

I’ve told the story many times, of how I came to his music. It begins with the New York Times. As a teenager—like 15 or 16—getting the Times felt like an event. The strong riptide of classical music pulled me toward the extracurriculars of buying CDs indiscriminately, like my purchase of a ‘no-name’ recording of the Chopin Nocturnes, my first classical recording, and how bewildered and disturbed I was hearing the pianist’s fast tempos and dizzying filigree. Or going to concerts, driving sometimes to Burlington, 45 minutes away, or to Boston, 3 hours.

But it also involved getting the Times, which made me feel connected to a larger world of classical music, whatever I imagined that might be from my little corner of Barre, Vermont.

I stirred up that classical music riptide, I should add. The bullying came so regularly, and so harshly, that I timed the occurrences, monitoring the space between and the nature of the event. Had it been exactly a week since someone last called me a “faggot,” or a week and two days? Had someone merely made fun of my hair or clothes, or chased me down the hall? Had the threat involved my death, or simply physical assault? In this context, and trapped by time, I needed…not quite escape, but refuge, a barrier, and the main candidate for that barrier seemed increasingly to be classical music, which over the course of ten years I had accrued some amount of skill in. The way I saw it, I could diffuse potential enemies with my talent, impress them. No longer just a faggot, but rather a faggot who played the piano, who had a skill they didn’t have. That skill, I also figured, could resemble intelligence, which could resemble power. If nothing else, it could create separateness, which I needed. Plus I could be distracted. I had seen others, boys I admired and to whom I, of course, had burning embers of attraction, devote themselves to music in their own way, and I wanted that. I let them get me high, I pretended to like Star Wars and sports, but mainly I immersed quickly into the culture of a performing, practicing musician.

So I began to practice. Staying late at school, the doors locked around me by custodians, to practice in the chorus room. Private and encapsulated by cement and brick, my sexuality undefined, I felt safe there and cavalier. I could do anything, and the next morning I would return to the land of the living to do my time in whatever classes were required. And so was more or less my relationship with music in high school.

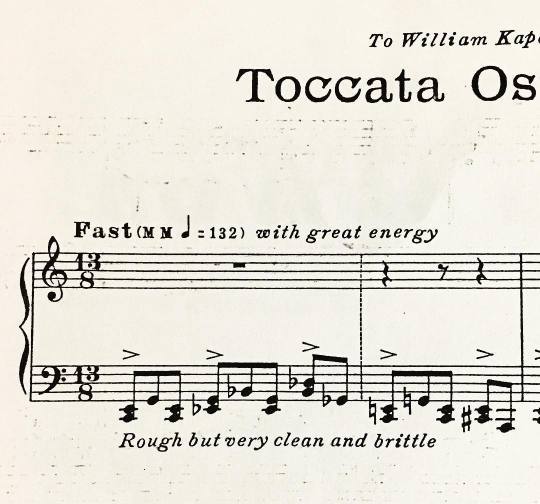

And I read the Times. One weekend it featured an article about the pianist William Kapell—namely a box set that encompassed most of his recordings. The story of his life, his nerves, his reputation, his talent, and his tragic death, all drew me to him. I don’t know how I got it, but somehow I did purchase that box set. And in that box set was a recording, what sounded like an encore, of Kapell playing a piece called Toccata Ostinato by one Robert Palmer. For years I listened to it with curiosity, particularly loving that the final chord sounded something like Kapell smashing the keyboard with both hands.

Probably years went by, but eventually I tracked down the score, discovering that it was indeed dedicated to Kapell. I also discovered that the last chord was a clean open fifth C sonority. In 13/8, and tangled with dissonant counterpoint, it would be years before I touched it. But I kept it with me.

And then, post music school, post fifty state tour, I eventually did learn it, note by note, beat by beat, using it as an encore for a rather subdued program I called Night Thoughts. People kept asking me after each performance (or even if they heard me practicing the piece), not about the program, which included music by Ives and Lang and Copland and Rorem—but about Palmer. And when I realized I had very little to tell them, I started digging.