On Towns in RPGs, Part 6: Wait, Wasn't This About Maps?

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

In the third,

I proposed an alternate metaphor: that cities are more like forests than

dungeons.

In the fourth,

I looked at how forests are used in D&D to see what we could use when

thinking about cities.

In the fifth,

I got into to the nuts and bolts of designing cities for use in D&D.

Now, we’re going to break out the Gimp (or,

for you fancy folks, Photoshop) and make

some maps.

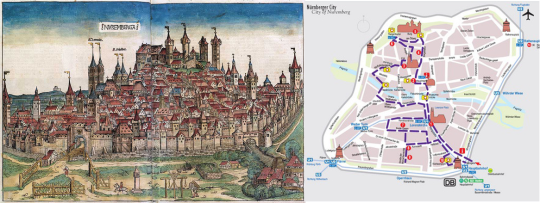

Back in the first article, I compared these

two images of medieval Nuremberg:

In that article, I argued that we can make

things easier for ourselves as DMs, and be more effective besides, by splitting

a D&D map into two separate illustrations: one to set the tone, and one for

crunch, much like the tourist map on the right. It’s ugly as sin, but if you’re

a tourist in old Nuremberg, it tells you exactly what you need and no more.

Functionally, this particular map wouldn’t be very useful in D&D (again, it

emphasizes actual streets, which we don’t care about, because towns

are not dungeons) but, because towns

are forests, we can look to existing high-functioning D&D map design—that

is to say, regional maps—as inspiration.

By adding an

illustration, which, unless you’re publishing this city, you can just steal

from the internet, you’re taking a lot of the load off of your map. The map no

longer has to be particularly pretty, it doesn’t have to show individual

buildings or roads, and it doesn’t have to fit any particular theme. All it has

to do is be easy to read, functional, and packed with information. Think about

it a little like a character sheet for your city.

Most D&D town maps

try to give a literal depiction of the exact layout of the streets (which isn’t

useful) and also serve as an

evocative piece of art (which is, but can be done better and more easily in

other means), but doesn’t provide much in the way of useful gameplay

information. So… what is useful

gameplay information?

Travel Time

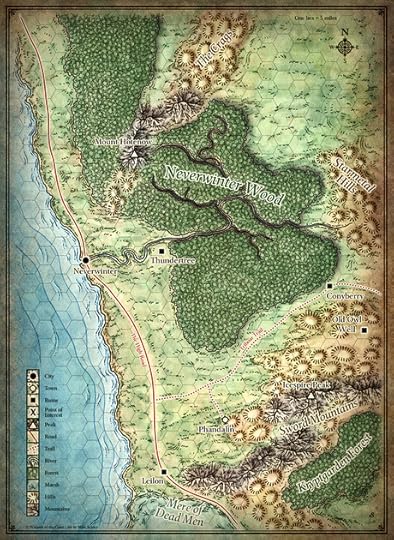

Consider the map of

the area around Neverwinter Woods that I used earlier. Somewhere in pretty much

every RPG rulebook is a table showing daily travel speeds through various

different terrain types. In D&D 3.5, for example, an unencumbered human can

cover 18 miles overland on flat ground, or 12 miles per day through forests.

These values can be increased by major highways. Knowing this information, it

becomes trivial for the DM to quickly count up hexes (which are 5 miles each),

look up a few numbers on a table, and do a quick calculation to tell the party

how many days it takes to get from, say, Neverwinter to Leilon (13 hexes→65

miles→24 miles per day on a highway→2.7 days travel time, rounded to 3). This

is important information narratively, but also for game mechanics, as it

determines how much food the party must carry (which plays into the encumbrance

and wealth rules), and how many random encounters they risk, well,

encountering.

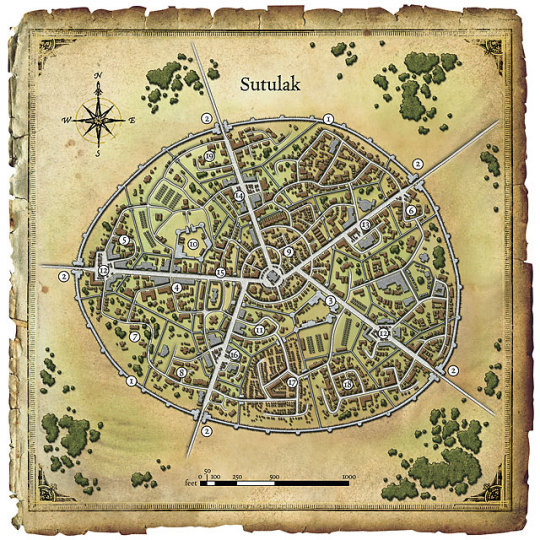

Now try to do the same calculation with

this map:

An unencumbered human can walk 300 ft per

minute, or hustle 600 ft in the same

time, though jogging through the city armed to the teeth (as most PCs are)

might attract attention. Try to figure out how long it takes to get from, say,

#14 to #18 on the map without giving up. There’s no grid of any kind, so you’ll

have to actually measure the distance. You can’t travel in a straight line

because of the intervening buildings except along the major highways, so you

can either measure it in chunks, or, I guess, use a piece of string or

something. Then take your measurement, compare it to the scale and divide it by

300 or 600 to find out how many feet it took to do such a thing, and then…

…realize that this number is actually

pretty useless. Even if you go through the above steps (which I can’t even

bring myself to do for this example, and would absolutely not do during play),

it’s not a helpful measurement. It doesn’t take into account crowds, traffic,

getting lost, being accosted by strangers, looking for a street sign that’s

hidden behind a bush, and all of the things that actually determine how long it

takes to get around in a city. So, like every other GM in history, you’ll never

look twice at the “movement per minute” table, never look at the

scale, never look at the map, and just say, “eh, it takes ten

minutes.”

If that works for you, that’s fine; you’ve

read a series of walls of text and won’t get much out of it. But if you’re like

me, you’ll always have a nagging feeling that you’re giving up.

The map of the region around Neverwinter

was created with the express purpose of being used in D&D. It is highly

specialized for exactly this purpose. The map of Sutulak here was designed, apparently,

to help with the morning commute of Sutulakers. So let’s turn the city of

Sutulak into the forest of Neverwinter.

We need to figure out the town equivalent

of forests, mountains, fields, and highways. Highways are literally highways—broad,

relatively straight avenues that cut through cities and connect key

destinations (such as a market and a gatehouse). As for plains, forests, and

mountains? They map pretty clearly to me as low, medium, and high-density

construction. Higher density leads to more confusing, twisty, and narrow roads,

as well as denser crowds, making it slower to move through these areas (both

because you risk taking the wrong turn, and you’ll be delayed by traffic).

Low-density is the opposite: the more spread-out the buildings are, the more

space there is to move between them, the less people there are doing so in the

first place, and the easier it is to see where you’re going and take the right

streets. If your town has large-scale natural elements, such as forests and

hills, they should also be included on the map. Sutulak here is criss-crossed

with bizarre inner city walls with limited chokepoint entrances, which should

also be included on the map.

Districts

In the fifth

article in this series, I argued that D&D towns should be thought of as a

small number of named, memorable districts (plus a couple of less-memorable

Hufflepuff districts). Each district can have its own distinct flavour, racial

makeup, police force, and random encounter table (if you use those), and a

memorable name.

Points of Interest

Critical buildings and

places should be marked with numbers that correspond to a key somewhere. For

the more artistically inclined, you could also pick out these buildings in

other ways, such as the Nuremberg tourist map’s large silhouettes of major

attractions.

Putting it Together

You’ve stuck with me

this far, let’s power through to the end. Let’s take this useless map of

Sutulak and turn it into a cutting-edge game aid, step by step.

1. Give it a grid. You can use a square

grid (like a pleb) or a modern,

high-tech hex grid. Either is absolutely fine. I just overlaid a hex pattern as

a new layer over the original one.

Counting distance is massively easier now.

No string or ruler needed; just count the hexes.

2. Highways and Barriers

The

various walls and highways criss-crossing the city are important both

narratively and mechanically, so let’s highlight them, too. Try to keep the

number of these small so as to be significant and memorable, don’t just connect

everything to everything else with a highway, because then we’re back at the

level of worrying about individual roads.

Red lines are highways and allow faster

movement; grey lines are walls and prevent movement barring some kind of skill check,

spell, etc. Crossing them may also be illegal.

3. Embrace Abstraction

This map still has a bunch of minor streets

and buildings confusing the issue. Here’s where we’re going to embrace full

abstraction by removing them outright. Stop seeing the trees, start seeing the

forest; there are no buildings or roads, there is only districts and density.

Let’s get this out of the way first of all: this won’t be pretty. With a proper illustration, though, it doesn’t need to be.

What I’m going to do is use different fill

textures to denote different types of hexes representing district and density.

District allocation is more of an art than a science; theoretically I could use

every walled-in subdivision as its own district, however, this crazy

criss-crossed town has too many of those to be memorable. Instead, I’ll combine

a few walled-in sections into districts, and in doing so, declare that they

have economic, cultural, and ethnic ties to each other. A real artist could do

pretty textures in these areas (like the forest texture in the Neverwinter

map), but as this is a test case, and I am not a real artist, I don’t want to

get too bogged down in aesthetics and I’ll use simple pattern fills.

Here’s the district map. Different angled

lines represent different neighbourhoods. There are five, which I’ve creatively

titled North, East, South, West, and Central. Each district (except central)

has at least one gate to the outside world and one highway. I’ve also moved the

walls above the grid layer (making them more visible) and removed the grid

outside the city as it was noisy and unnecessary.

Now we can inject building density into the

equation. Building density implies population density, which tells us how

narrow, twisty, and crowded the streets are, which finally solves our ‘movement

rate’ question.

Here we have it: five districts, clearly

delineated from each other through textures, and density represented by weight

of the lines. Central district there is packed, as befitting a city center, so

the entire district is at maximum weight. Because moving through cities has

little to do with your physical movement capabilities and more to do with

traffic and navigation skill (a Ferrari wouldn’t get you through traffic any

faster than a Honda), we can largely ignore a character’s movement stat and

base movement just off of hex density. Maybe we can come back to this, but for

the time being, let’s say you can move through low density hexes (with little

traffic and lots of clear sightlines making for easy navigation) and highways

at a rate of 3 hexes per minute, medium density hexes at a rate of 2 per

minute, and high-density hexes at a rate of 1 per minute. Highways boost speed

not only because they are broad and straight, but also because it is much

harder to take a wrong turn on them and have to double back.

If you wanted a coarser grid, you could

make each hex 300ft, and say that it took you 1 minute to move through a light

density hex, 2 minutes to move through a medium density hex, and 3 minutes to

move through a high density hex.

I also added points of interest numbers in

this step. If I were to do it again, I’d make them more distinct, such as using

the original map’s white circles, or perhaps with stylized building

silhouettes, like the Nuremberg tourist map.

Districts can also be denoted using colours,

with darkness and lightness indicating density, perhaps given borders like nations

on a world map to distinguish them a little more from each other. Gates between

walled prefectures are also important enough that maybe we could borrow a

little from dungeon maps and give them a bright, visible “door”

symbol. Also, the medium and heavy weighted areas are a bit too similar looking

for my taste, so improvements could be made there, as well.

Still, I think this is the right direction.

I’m going to let this idea percolate for a while, and maybe try it out in a

game or two of my own, before tinkering with it too much.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers