L'art c'est moi

George Brecht, "No Smoking"We are overwhelmed or taken over by the image of the artist. That is what stands between us and the art.

George Brecht, "No Smoking"We are overwhelmed or taken over by the image of the artist. That is what stands between us and the art.Yesterday, I found myself, almost totally unexpectedly, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) with the French-Canadian poet Steve Giasson (whom I was trying to meet), the English poet Phil Davenport (whom I had no idea was in New York City). I drove from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to New York City to meet up with Steve and his fiancé Martin, both of whom I'd met at the Text Festival in Manchester, England, earlier this year.

Once at MoMA, I knew what show I wanted to see, and it was the show Steve and Phil wanted to see as well. It was the reason they were there. We are made from the same substance and are draw to the same things, drawn out of ourselves, and drawn onto the page.

Yet we were entirely different. I come a background that is, to some degree, curatorial, so I keep my distance from the pieces on display, though I tend to get very close to them. Phil, however, managed to make the guards nervous twice while he was engaging with the pieces, and once I had no idea what their issue was.

When I'm at an exhibit, my intensity of focus wipes much thinking from my brain. I don't talk much, I peer, I perceive, I exist, but this intensity isn't slowness. I move through space. I review a wall of works in a glance and find something that requires my attention. I read a label. I eat a word. I eat an image. I follow a line and watch everything on it move past me like a filmstrip. When I interact with the works, as I did yesterday in that sparsely attended exhibition, I sing quietly and might record it as I do. I am of the works before me, made out of them. I am paint and ink and paper and canvas and metal melted than rusted into place.

Phil and Steve were talkers. Their peering made mine look like glancing. They moved through the rooms with a deliberate slowness, a ravenous attention. And works would stop them in place for minutes and cause them to have thoughts and to talk animatedly to each other about the works. They were not hoarding sustenance for the winter; they were sowing a field and growing a crop.

What were two separate activities for me were a melded whole for them. It was a beautiful thing,

[image error] Martin Vinette and Steve Giasson beside an Exhibit of Fluxus Musical Instruments, MoMA (23 October 2011)

and outside the realm of my desire to emulate. If they were raptors soaring high over a field and surveying everything as a piece made of pieces (they were constructors of wholes, of intentions), I was a field mouse moving quickly, pausing at a smell or sound, raising my nose slightly, perceiving, moving on, and given over to the beauty of the little pieces before me, pieces I could not tell were a field.

In one of the rooms, Phil stopped to discuss one of the thoughts he had, and it was how ironic the exhibition was, because most of these Fluxus pieces were meant to be manipulated, to be interacted with physically. (It was a thought I had encountered, particularly when watching the pieces filled with drawers or the Tactile Box, into which a percipient was to slip a hand to feel, but not see or even smell, the art—but it was also a thought I let float away, unready to entertain considerations of the scenes flashing by before me.)

When Phil made his point, I agreed, but only before disagreeing, noting that a display, for design's sake, of spoons (each meant to be used, to be interacted with) might not elicit this thought from Phil, but that that would be just as ironic. The maker had intended the spoon to be used, but curatorial practice made the use of the spoon verboten. Phil did not agree with me, pointing out again the intent of the artist.

And that is when I saw it: We imagine the intent of an artist to be special, to be (actually) more intentional than the intent of a craftsperson or a designer or a dabbler. We allow the artist to be the device through which we see the art, and thus we are always a step away from the art, trying to crane our heads around that person so that we can see the thing itself.

But maybe there isn't the thing itself.

After Fluxus, after standing by a staircase and front of a huge wall of George Brecht's "No Smoking" for minutes talking (though I took more pictures and said fewer words), we broke into two, some of us going to the de Koonig show on the sixth floor.

Now, de Koonig is no favorite painter of mine (that is Paul Klee), but I can appreciate his talent and the way it wrenched himself from physical place to visual space, even as his interest in breasts continued unabated.

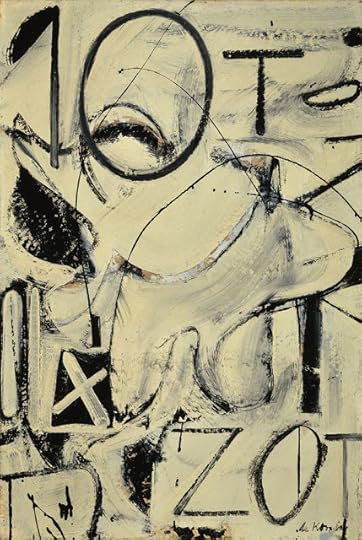

Willem de Koonig, "Zurich" (1947)

Willem de Koonig, "Zurich" (1947)Although this retrospective showed that de Koonig was hugely talented even as a twelve-year-old, and even though this exhibition was filled with huge and colorful paintings, the first paint I saw and loved was a small one called "Zurich." The title seemed strange, given that the meaningless but polysemous word "ZOT" filled the bottom right hand corner of the canvas. Essentially a bitonal piece, it captured my imagination by being a visual poem, by being about the painterly presentation of word and letter. From a distance, I pointed out the painting to Steve and Martin, noting that it was a visual poem.

But what bothered me about the painting, what bothered me about the exhibition as a whole, was something small, something most people didn't really pay attention to: it was "de Koonig." I don't mean the painter per se, but certainly him, too; I mean his name, which was painted on every canvas, thus disrupting the tableau, which in this case was of word and letter and color.

This signature because to bother my old concretist tendencies. The mid-century concrete poets generally produced works of such rectilinear precision that adding a signature, a clearly foreign beast, would destroy the structure of the poem. So they generally removed themselves from the scene, leaving only the scene itself.

It has been what I have aspired to.

At some point, a crowd of us was huddled in a circle, and Steve and I were talking about our work. Steve is a massive and splendid appropriator, pulling together words (generally in English, though his tendency in speech is francophone) from different sources to create conceptual pieces. Martin explained all the arts Steve had moved through to become, eventually, a poet, and Steve explained how, even in poetry, he had moved from lyric poetry into his hardcore (my term) stance.

I noted that I've never given up on any mode of expression, that I continue to write lyric poems, emotional poems, narrative poems, along with much else. Steve said he enjoyed my sound poems, having sat just behind me in Manchester when, while standing in a cone of spotlight, I'd sung a strong good sound poem into the enveloping darkness of the theater. And he said that he saw my work as radical, not traditional.

I noted that my work was various, and then I made another connection: that my tendency now is performative, that I am trying to create an art that disappears into the ether, even as I try to catch it, to hold it in place, with recordings. Martin and he were surprised that my poemsong was extemporaneous; they, as many others have, assumed I was singing a piece I had memorized.

But I am not made of memory, only memories.

After walking into another room of paintings, I ran across another painting of de Koonig's of a visual poetic nature, and it was entitled "Zot." I found it interesting that de Koonig had created (I almost wrote "had written") two paintings two years apart both with the word "ZOT" painted into a lower corner. I wondered if he had done so intentionally, for the paintings are quite similar, or if his own tendencies just pushed him in the same direction once again.

[image error] Willem de Koonig, "Zot" (1949)

And I wondered if de Koonig, even as he wrenched his style from place to place, could ever escape himself. I wondered if he worried about being between his art and his audience. I wondered if he always saw himself when he saw one of his paintings.

During our earlier discussion of artistic intention, I noted that bpNichol had once produced a small leaflet poem that was intended to be burned. To make the poem, to complete it, the reader had to set it afire and watch it blacken and burn. In this way the poem would be made into itself. Yet, I noted, not everyone burned the poem, because we are all a part of the irony. We are all liars when it comes to intent, and we all want two things at once.

So the readers want to save the bpNichol object, to objectify it. So the Fluxists sold their works. So the curators preserved these works by making sure they were not used as intended. So the audience paid an admission to see some pieces meant as throaways. So the humorous and arch Fluxists became seen as serious and separate from themselves. So it took decades for de Koonig to depart from representation. So the visual poet sees visual poems where others see paintings.

So what I imagine the artist should be is the art itself. So I assume the only way to destroy the artist so that the art can be seen is to make the artist the art itself. So I dance and sing and write a poem, and yet I am so separable from the dance, the song, the poem.

So even the words that come out of my body, from the deep source of themselves, are not me at all. So maybe I am not either.

So, so.

After a brief stop at a coffee shop, where the crowd of us ate and talked about everything, and only about poetry, at the place where Phil had his first egg cream (which is nothing like what it sounds it will be), where we spoke in languages about language, at the coffee shop that closed before dinner so we closed it down, we stood outside talking in the growing cold before walking a short way together and then parting.

A bit more than an hour later, I was driving north out of the city. After stopping for the night, I stayed up until 2:45 doing something for my son Tim (something that, ironically, he ended up not needing me to do). The room I slept in was cold, and my thin frame shivered during the night, so I slept fitfully and for only three and one quarter hours. Yet I went to work today, and even worked an extra long day, writing many pages of text as I moved through time. Yet I came home and ate and wrote, after so many days of silence, this huge essay about my yesterday thoughts, those few I've held onto.

Because I am an artist, so I am always getting in the way of my art.

If I've made any sense here it is an accident of nature, something that happens only because I've done so much writing in my life that it is a form of breathing. As I try to turn into my art itself, I push myself, ever so much forcefully, in front of my art.

So no-one can see it.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on October 24, 2011 18:51

No comments have been added yet.