A Revolutionary Space of One’s Own -- A Review of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom

A Revolutionary Space of One’s Own : A Review of Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom by Tyler Bunzey | @t_bunzey| NewBlackMan (in Exile)

When Black Lives Matter gained international attention in the wake of the public murder of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, much discourse of the organization was focused on its leadership by three Black women—Patrice Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi. Coverage focused on how Black Lives Matter organized itself to be radically inclusive, eschewing the cisgendered, male, Black Messiah style leadership that has marked popular Black liberation movements throughout America’s history. Black Lives Matter is unique because it does not have a centralized leadership style thus allowing groups who have been traditionally underrepresented or elided altogether from Black freedom movements the ability to participate in and define the movement—namely Black women, LGBTQ+ people, and the working class. Black Lives Matter dramatically departs from the Black protest tradition by empowering marginalized voices in the Black community to speak back to oppressive power structures both without and within the community, and the organization is rightly lauded for its public shift from traditional Black protest strategies that envision Black liberation through masculinist discourses.

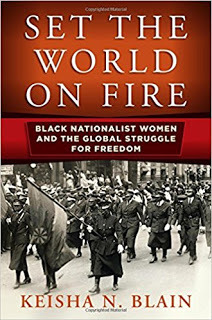

However, Black Lives Matter is not the first movement in American history to have Black women openly leading the Black community in resistance to oppressive racist structures. Keisha N. Blain’s Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom details the key role that women played in Black nationalist movements in the early 20thcentury. By detailing the lives and strategies of women in key leadership positions in American Black nationalist movements, Blain retells a history that has been traditionally associated with the masculinist discourses of Marcus Garvey and Malcolm X and traces a more consistent historical arc of Black political discourses from the early nationalist movements with Garveyism through the Civil Rights and Black Power eras.

Focusing on key female Black nationalist leaders like Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, Celia Jane Allen, Amy Jacques Garvey, Maymie de Mena, and others, Blain’s historiography resituates women as not just key participants in 20thcentury Black nationalist politics but as figures that were foundational to the movement itself. Blain’s work serves as “an exploration of how Black nationalist women ‘on the margins’ struggled to make their way to the center—that is the forefront of political movements for global Black liberation” (10). Highlighting the inventive and occasionally scandalous techniques that Black nationalist women used to promote their cause, Set the World on Fireinterrogates the complexities of Black nationalist women’s ideological formations in the movement itself. Blain’s careful study significantly problematizes the master narrative of Black liberation’s history in the United States of being propelled only by central male figures like Marcus Garvey, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, and in turn demonstrates how Black women were committed to a global sense of Black liberation, Pan-Africanism, and diasporic citizenship from the height of Garveyism until the Black Power era.

Blain’s account of Black nationalist women’s participation in liberation movements begins by detailing how women engaged with Garveyism and the traditional account of Black nationalism in America. She details the role of Amy Jacques Garvey, the second wife of Marcus Garvey, and her co-leadership of Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). The UNIA’s political platform consisted of traditional understanding of Black nationalism—racial separatism, Black emigration to Africa, Black capitalist economic empowerment, but significantly it allowed space for “Black women…to engage in political activities outside of the expected parameters of home and family” (21). There were no by-laws in the organization that prevented Black women from holding leadership roles over men, and thus women were enabled to fill non-domestic, robust roles in the fight for Black liberation. Jacques Garvey used this space to promote the Black nationalist agenda of Black emigration to Liberia, and she was able to assume temporary authority of the UNIA after Garvey’s imprisonment in 1925.

Jacques Garvey advanced the Garveyite nationalist agenda even after her husband’s death, and her writings from Jamaica “endorse[d] anticolonial policies and challenge[d] global White supremacy—outside of the grasp of U.S. officials who had managed to silence some Black nationalist activists while intimidating others” (163). Jacques Garvey’s lifelong participation in the Black nationalist struggle both in the U.S. and abroad and her leadership within the UNIA was a radical departure from organizations like the NAACP which retained limited roles for Black women and certainly did not afford them an equal political voice. Jacques Garvey inspired women like Mittie Maude Lena Gordon to promote a Pan-African racial understanding that supported universal Black freedom around the globe, and Blain’s account of her participation in the UNIA suggests that Garvey was not the only influential figure determining policy within the UNIA. Black women like Jacques Garvey were not simply influencers within Black nationalism; they were the creators, disseminators, and leaders of the political movement itself.

While there were no by-laws in the UNIA preventing women from having authority over men within the organization, there was still an implicit bias in that prevented women from fulfilling robust leadership roles throughout the U.S. This disparity, along with some ideological disagreements, caused UNIA member Mittie Maude Lena Gordon to break off from the organization to form the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME). The PME, based in Chicago, rose to prominence in the wake of the fragmentation of the UNIA post-Garvey’s deportation, and its organization was even more radically inclusive than the UNIA. Gordon ensured that women had “greater visibility and autonomy” in the PME than in the UNIA while retaining the same dedication to Pan-Africanism and Black emigration with which Black nationalism has been traditionally associated (45). Combining Garveyism with the teachings of the Moorish Science Temple of America, Gordon created a “crucial space for working poor Black men and women to engage in Black nationalist and internationalist policies” and was dedicated to the economic and political empowerment of American Black subjects through relocation and emigration. A key proponent of various bills to relocate Black Americans to the American colony of Liberia, Gordon was the “Moses” of Black nationalist women in the period after Garveyism was prominent.

Blain’s narrative of Black nationalist women does not just focus on Black nationalist activities in the urban North; she also includes the work of Celia Jane Allen, a PME activist who canvassed the Jim Crow South to spread nationalism among the rural poor. Allen’s strategies in the South were propelled by the “grassroots and community-based tradition of struggle…which allowed for identifying and nurturing local leaders” (78). This proto-feminist aim allows the needs of the communities to be met and advocated for individually without sacrificing collectivism or universal concern for others. Allen advocated inflection of the local through the global and thus allowed Black women to see themselves not as fulfilling simply a role within a larger machine but to be empowered to actively engage in the political struggle on a grassroots level. Allen’s work engaged the South in Black nationalist politics and drew Southern women into the greater network that organizations like the UNIA or the PME.

While Blain’s history of these Black nationalist women’s leadership within the movement is compelling and significant, she is unafraid to explore the more problematic aspects of the Black nationalist struggle. While Black nationalist women often advocated for a type of proto-feminism, they also “attempted to uphold the patriarchal and masculinist ideals generally endorsed by Black nationalist organizations” (68). The organization still privileged male leadership as ideal promoted a more nurturing role for women within the Black nationalist struggle. Black nationalist women also advocated for a “civilizationist” view of Liberia’s colonization, and their arguments for U.S. funding of Black emigration to Liberia often included appeals to civilize natives of Liberia and to develop a capitalist economic system to tame the wild land of the West African country (89). The civilationist appeal of many Black nationalists, coupled with a biologically determinist view of race, caused them to turn to an unlikely and questionable ally in their struggle for universal Black freedom—White supremacists.

Blain’s history of Black women nationalists is unafraid to examine how activists like Allen and Gordon turned to Southern secessionists and White supremacists to gain U.S. national support for Black emigration. Working with notorious racists like Ernest Sevier Cox and Theodor G. Bilbo, Black nationalist women often performed politics of racial and gender inferiority in order to get White supremacists in power to advocate on their behalf. Although Black nationalists and White supremacists like Bilbo and Cox were often at the opposite ends of racial ideology, they “both rejected racial mixing and desired racial separatism…[so] they often stood on the same side of the emigration issue” (100). This partnership was not a desperate attempt by Black nationalists to gain political power, however; according to Blain it was a calculated, strategic, and rational move to manipulate those in power to serve what Black nationalists saw were the needs to the Black community—self-determination through racial emigration (105). Blain deftly configures this choice by Black nationalist women as both questionable and understandable, both paradoxical and potentially politically expedient.

While Blain’s explicit narrative details specific Black nationalist women and their contribution to the movement throughout the early 20thcentury, there is an implicit argument to the importance of place in the Black nationalist thought that these women promoted. Chicago is the beating heart of Set the World on Fire, and the city served as a locus of change, hope, and movement for Black women who may be marginalized in other spaces. This significantly departs from the traditional narrative of Garveyism and Black nationalism as being catalyzed by New York City and Harlem, and thus Chicago can be read as a space of nationalism for Black women specifically. Likewise, Liberia, and later Ghana, were “utopian” visions for many of these activists, ones that were not necessarily rooted in any sort of geographic or political reality and were instead rooted in an ideological constructions of “unlimited possibilities” (105). For these women, these possibilities did not just include the traditional understandings Africa in Black nationalism that situate the continent as a site of racial possibility; Liberia and Ghana were also sites of gender liberation in which the Black nationalist women, limited by patriarchal strictures in the States, could reconfigure their role in society. There is a clear spatial frame to Blain’s history that decenters spaces of old nationalisms and aims to imaging new ones across the Atlantic.

Blain’s Set the World on Fire is more than a revision of Black nationalist history or an inclusion of women’s voices within that history. It serves as a radical departure from the mythology of Black leaders throughout American history, a mythology that no real historical figure could live up to regardless of their brilliant contributions to Black political life. She resists valorizing Black nationalist women beyond what is due to their legacy, and by including their shortcomings along with their successes, Blain develops a methodology of historical analysis that allows the messiness of politics to exist as it is. Blain lets Black nationalist women to speak for themselves and in turn lends them the agency that the historical record has denied them. Like the aims of Black Lives Matter today to include the voices and concerns of those historically marginalized by Black political discourse, Blain’s Set the World on Fire allows Black nationalist women a voice in the historical record to speak on their radical vision for Black empowerment and disaporic citizenship. Blain’s work is more than a history or a retelling of women’s role in the Black nationalist movement; it is a feminist revision of the methodology of historical analysis itself. +++

Tyler Bunzey is a Teaching Fellow and Doctoral Student in Department of English and Comparative Literature at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill. Follow him on Twitter: @tbunz3

Published on May 16, 2018 19:02

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.