On Towns in RPGs, Part 2: Towns are Not Dungeons

In the previous

article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined quest to figure out

what, if anything, a town map is actually for

in tabletop play. If you just stumbled on this post, I encourage you to go

back and read part 1. Go on; I’ll wait.

In almost any discussion of urban adventures,

someone—whether it be a blogger online, or a writer at Wizards—will helpfully say

something like ‘a city is just another kind of dungeon.’ In particular, this crops

up in official Dungeon Master’s Guides:

The

“cobblestone jungle” of a metropolis can be as dangerous as any

dungeon.[…]

At

first glance, a city is much like a dungeon, made up of walls, doors, rooms and

corridors. Adventures that take place in a city have two salient differences

from their dungeon counterparts, however. Characters have greater access to

resources, and must contend with local law enforcement.[…]

Walls,

doors, poor lighting, and uneven footing: in many ways, a city is much like a

dungeon.Dungeon Master’s Guide 3.5th

edition, 2003. p.

98

Although

they hold the promise of safety, cities and towns can be just as dangerous as

the darkest dungeon. Evil hides in plain sight or in dark corners. Sewers,

shadowy alleys, slums, smoke-filled taverns, dilapidated tenements, and crowded

marketplaces can quickly turn into battlegrounds.Dungeon Master’s Guide 5th

Edition, 2014. p.

114

On the surface of it, this seems like a

very useful comparison, as dungeons are comfortable environments for players

and GMs alike, while adventures in cities and towns are a new, confusing

prospect. By drawing comparisons between the unfamiliar (an urban adventure)

and the familiar (a dungeon adventure), the Wizards RPG team can turn the

unfamiliar familiar and thus ease a GM’s fraying nerves.

Of course, it’s absolutely garbage. A city

is nothing like a dungeon.

Now, this is not to say that a city can’t

be twisted into a dungeon (for

example, the city is in ruins, the city is underground, the city is under siege

and full of barricades, everyone in the city has turned into zombies, etc.) in

much the same way that a temple, cave network, castle, or any feature can be

twisted into a dungeon. This might even be a fun adventure, but it isn’t a city—at least, not a typical

one. A normal city, even a pseudo-medieval one, without exceptional or

fantastical elements, is nothing like a dungeon. And here’s why.

Dungeon movement is all about restrictions,

while city movement is precisely the opposite. Dungeons are designed from the

ground up (or, more often, the ground-down) to make traversing them as difficult

as possible, while cities, to a greater or lesser degree, are built to

facilitate the movement of people, goods, and money. Rivers are bridged, slopes

are terraced, rust monsters are driven out.

You only have to look at a map of a dungeon

and a city to see the difference.

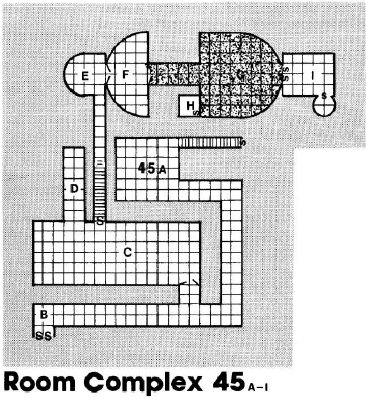

In this example from the classic Caverns of Thracia by Paul Jaquays, you

can see how constrained movement is—you can’t simply go from I to A; you must

first go through G, F, E and C—each with their own features and hazards the

party must overcome.

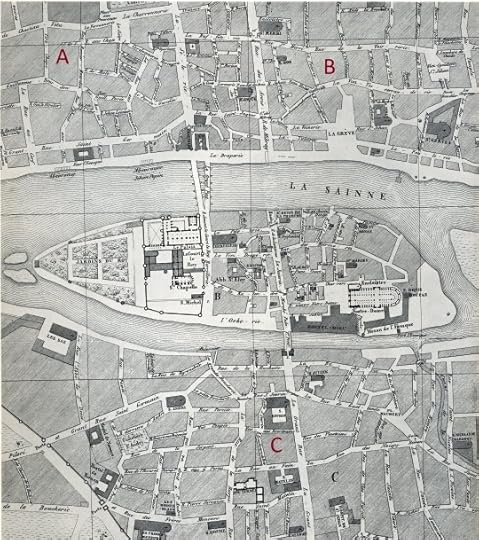

Now compare this historical map the

internet assures me is of 14th-century Paris:

Technically, in the map above you can’t

move directly from A to B without taking several twists and turns (much like

you I to A in the Caverns of Thracia),

but at the same time—who cares? Nine times out of ten, the GM will simply say

“you get there,” and for the remaining one time out of ten, she’ll just

roll on a table to see if something happens to you along the way—something quite

unrelated to specific location.

Getting from point A to point C is a

different matter, as you have to cross a series of bridges and an island to get

there, which can be important from both a narrative and mechanical standpoint

(perhaps there’s a toll, or the bridges close after dark, or only those allowed

by the Marquis can cross the bridge, or whatever). Note that you don’t need to

know anything about the layout of

roads and buildings to see that these bridges must be crossed.

In the map above, with the exception of the

bridges, which are a rare example of a natural urban chokepoint, there are

countless routes from any one point to any other point. While the degree

depends on the setting, cities have been planned with exactly that idea in

mind—they are designed using every practical means to facilitate travel from any

location to any other location. Facilitating travel means facilitating

commerce, which directly translates to the wealth and power of the lords and

ladies running any large settlement.

In short: movement in a dungeon is virtually always highly restricted,

while movement in a city is virtually

always highly unrestricted.

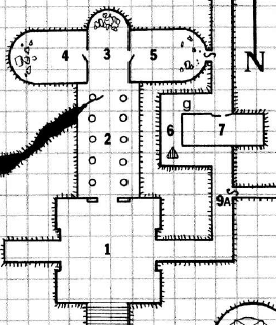

In the dungeon map above—also from Caverns of Thracia—a baker’s dozen

sorcerers could light up area 1 with Fireballs

and the default assumption of both players and the GM is that the lizardmen in

area 7 would be none the wiser. This stands to a cursory amount of logical

sense—rooms are separated by thick walls of stone and heavy doors—but mostly,

it’s due to real-world logistical reasons. When the party is in area 1, the GM

has her dungeon key open to area 1 and area 1 alone. To check what’s going on

in nearby rooms, the GM would have to flip through several pages—often at

opposite ends of the book, especially in cases of multi-storey dungeons—and it

would almost never matter. The rare exceptions to this rule are written

directly into the dungeon key:

6) Spear Trap: As the location of the “6” is passed

on the map, there is a 1-4 chance on a D6 that 2 spears will come flying out of

the south wall, headed north and hit as if cast by a 7th level

fighter. There is a 25% chance that the Gnoll guard, AC: 5, HD: 2, HP 13,

Weapon: Morning Star, will be dozing at point “g.” If he hears approaching adventurers, he will slip into Room 7

and the Gnolls in there will have an ambush ready.Paul

Jaquays, The Caverns of Thracia,

1979. p. 23 (emphasis mine)

In the above example, Jaquays specifically

calls out a rare inter-room interaction—that the dozing gnoll sentry will go

and alert his comrades. This prevents the previously-mentioned page-flipping

headache, as the GM knows exactly where to look, and can safely ignore all

other rooms

Except in specific cases mentioned, a

common abstraction is that a full symphony orchestra could play in one room,

and have little to no effect even in adjacent rooms.

In a town, the same thing is not true

whatsoever. If the party opens fire on Alchemy Street, people are going to care—kind

of a lot—and are likely to do something about it. Even in a building, the

presence windows and thinner urban walls means that people outside might come

and investigate a commotion. Civilians might run and hide, the militia might

get called in, and the party will be dragged before a magistrate.

In a dungeon, unless specifically mentioned,

everything and everyone is isolated from each other. In a city, the opposite is

true—everyone and everything are in constant communication. Great efforts have

to be gone through to achieve real isolation in an urban environment.

is Life or Death

Another major distinction between a dungeon

and a city is the density of threat. I maintain that, short of an active warzone,

even the most crime-ridden, poverty-stricken slums are safer than even the safest

of dungeons. If some PCs get drunk and wander, unarmed, through the worst neighbourhood imaginable, there’s

still a pretty good chance they’ll get through unmolested. Failing that, they

might be mugged. Actual murder or assault is possible, but pretty unlikely. These

things happen, and maybe even every day, but not to every person every day. Someone, after all, has to actually live in

this part of town. Often quite a lot of someones. In a dungeon, those same PCs

will be eaten alive with no

possibility of survival. In a dungeon, it’s not a question of if the floors will collapse to reveal a

30-foot drop to poisoned spikes, but when.

This level of threat is why every hallway,

door, and intersection matters. A

dead-end isn’t merely a delay, it’s another roll on a Wandering Monster table.

A locked door doesn’t just mean “go back to the intersection of Oak and

Fitzgerald and hang a left and we’ll go around,” it means pick the lock or

face the possibility that you’ll never see

what’s on the other side of it. This might mean missing a powerful magic sword

that would be the difference between life and death when, two hours later,

you’re face-to-face-to-face-to-face-to-face with a hydra.

If you try to run a city with a similar

density of threat (that is to say, rate of wandering monsters, traps, and so

on), it’ll take five sessions just to get from the gate to the inn, and Pelor

help you when you’re just leaving and realize you forgot to get another fifty

trail rations each.

As mentioned previously, I appreciate the

rationale in trying to compare a dungeon to a town in order to make the

unfamiliar familiar, but I think the products of such a comparison lie

somewhere between unhelpful and harmful. In a way, that makes the Dungeon Master’s Guide 3.5th

Edition correct: “Walls, doors, poor lighting, and uneven footing: in

many ways, a city is much like a dungeon.” This statement is absolutely

correct, but, I contend, the listed features are the only ways a city is like a dungeon.

Now that I’ve found what a dungeon is not, in my next post, I’ll take a stab

at determining what a city is.

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers