Stuart's Daily Word Spot: The comma, and how to use it.

Cover via Amazon

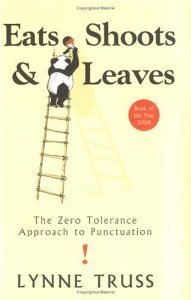

Cover via AmazonThe comma, and how to useit.Perhaps I should startthis piece by determining what a comma actually is: a comma is defined as apunctuation mark that indicates a pause between parts of a sentence, or whichseparates items in a list or groups of figures, etc. In speech, we pause whenthere's a natural break in what we're saying, or when we need to isolate thenext words from those preceding them in order to make our message clear.There's a movement towardopen punctuation at present, promoting the omission of commas in cases in whichthey're considered optional. Whilst such an idea may have some merit, writersand editors need to retain commas, and sometimes even insert additional ones,in order to clarify meaning.Let me give some examplesof how important the humble comma can be.

There is, of course, thefamous example shown by Lynne Truss in the title of her excellent book, 'Eatsshoots and leaves.' and its alternative version, 'Eats, shoots andleaves.' The two sentences have exactlythe same words but the meanings are poles apart. In the first, we have a baldstatement that the subject (unstated in this case) lives on a diet of shootsand leaves; a vegetarian, of course. In the second, we have an altogether moredangerous individual who has a meal, then produces and uses a firearm beforemoving away.

'She sees all the advantagesand wonders about how they might make more of these qualities.'

In this example, the pairing of 'advantages'with 'wonders', which can act as both verb and noun, makes the first part ofthe sentence sound as though the subject, she, observes all the advantages andwonders. In fact, of course, the writer does not intend the reader to make thisconnection and the sentence would be much clearer if written thus: 'She seesall the advantages, and wonders about how they might make more of thesequalities.' We now know, with certainty,that 'she' is both observing and speculating.

It is this ability of thecomma to remove ambiguity that makes it an essential tool in the writer'sarmoury.

'You should be gratefulfor the money and rest.'

Does the writer want hissubject to show gratitude for cash and repose? Or does he actually expectgratitude for the money alone and then suggest that his subject take a rest?The sentence can be read to mean either. A comma would clarify the latter: 'Youshould be grateful for the money, and rest.' This is now clear. As for theformer case, a slight restructuring of the sentence will again make the meaningclear: 'You should be grateful for rest and the money.' Again, the meaning isnow clear.

'The world contains fartoo many people using artificial means to produce children and far too many orphans.'

Here we have the slightlysinister suggestion that people are using artificial means to create orphans.Does this mean some people are actively killing parents so that some childrenwill be orphaned? I think the writer means something entirely different: 'Theworld contains far too many people using artificial means to create children, andfar too many orphans.' Again, thissentence would make more sense and be unambiguous if structured in a betterway: 'The world contains far too many orphans, and too many people who useartificial means to create children.' You may, or may not, agree with thesentiment, but I hope you agree with the clarity of the alternative structures.

'Marilyn opened the door in her nightdress and shrieked as the chill airblew it up her legs.'

It's unlikely Marilyn's nightdress had a door, of course. But the writerhas described the garment as having one. Also, was the door or the nightdressblown up her legs? Not at all clear, is it? Perhaps a better understanding ofwhat actually happened would be derived from: 'Marilyn, in her nightdress,opened the door and shrieked as the chill air blew it up her legs.' Even here,though it's now clear that the nightdress and the door are two separate items,it remains ambiguous whether the chill air blew the garment or the portal upher legs. It isn't always a lack of commas that renders a sentence unclear.Perhaps it might be better stated as: 'Marilyn opened the door and shrieked asthe chill air blew her nightdress up her legs.' Here the comma has been ditchedbut the structure of the sentence makes everything clear.

'Another politician named Nick Clegg broke his word and allowed hispartners to introduce tuition fees against all the pre-election promises he hadmade.'

How many politicians named 'Nick Clegg' are there? And, in what way canyou introduce tuition fees for pre-election promises? The sentence is poor and lacksclarity. Let's try: 'Nick Clegg, another politician, broke his word and allowedhis partners to introduce tuition fees, against all the pre-election promiseshe had made.' We now understand that the writer is lumping Nick Clegg withother politicians and pointing the finger of blame at him, regarding tuitionfees, because he had previously promised not to permit such a thing to happen.

I could go on with examples, and Icould talk about the 'Oxford' comma, but I think you've probably got thegeneral idea by now. I don't want to bore you.

23 October 2001 The firstiPod was released by Apple. Can it really only be ten years ago?

Published on October 23, 2011 03:30

No comments have been added yet.