How do you persuade USAID to adopt Adaptive Management? An insider’s account

Over the next few months, I’m hoping to get my amazing LSE Masters students to contribute the occasional blog – following yesterday’s post on interesting thinking at USAID, here’s a taster from

David Yamron

following yesterday’s post on interesting thinking at USAID, here’s a taster from

David Yamron

What happens when you try and put Adaptive Management into practice in a large aid bureaucracy? I spent two years finding out at the biggest of them all – USAID. For the two years prior to my studies at the LSE I worked as a contractor on a USAID project called Measuring Impact. Measuring Impact (or MI, as it was inevitably christened) is a five-year, $20 million project based within USAID’s Office of Forestry and Biodiversity. The purpose of the project is to institutionalize adaptive management and effective monitoring, evaluation, and learning within USAID projects in our little corner of the Agency.

It’s important at this juncture to briefly elaborate on what we mean when we talk about adaptive management, because I find that many people turn off when they hear buzzwords. But adaptive management is at its core a simple idea. At MI we were trying to get teams to design projects by understanding their context, plotting the outcomes they wanted to achieve, and building a theory of change to get from the former to the latter. From there, during implementation we pushed them to periodically reexamine their theory of change and outcomes, assess their progress, and make changes to their implementation strategy based on new information, all the while documenting their work so that future projects could learn from their experience.

It’s perfectly straightforward….

After I had described this process at a recent panel event at the LSE, my professor (the proprietor of this very blog) said, half joking, that this was revolutionary. And he was right. While these aren’t radical ideas, their operationalization represents a massive change to the way things are done in development, and change is always a threat. This is doubly true in a big bureaucracy like USAID. What MI was trying to do is make people design more effective projects, and to better define outcomes of those projects. Stakeholders can see this as a risky proposition. After all, USAID projects are used to reporting on output targets, like training hours, which are relatively easy to hit. The challenge of MI was to get those same projects to design their indicators, monitoring processes, and reporting processes to answer the question, what did we really achieve with this project? Trained some teachers, OK, but how did that actually affect test scores in your region of Indonesia? How many fishers in this Philippine village are actually using the sustainable fishing practices they’ve been trained in?

There is massive opposition to these sorts of changes. On the USAID side, mission staff often don’t want to make time for passing “fads” like adaptive management. New currents in development thinking can be seen as an imposition because funding cuts mean smaller and smaller cohorts are having to work harder and harder: just another thing that Washington makes me do, just more admin work that I don’t need to do because I already know how to do my job. While understandable, this is dangerous thinking. As we know, adaptive management processes sometimes show that certain interventions actually aren’t effective. That’s a hard pill to swallow for people who have built careers implementing, say, sustainable livelihoods programs. That being said, because of the decentralized nature of USAID, if a given mission’s leadership supports adaptive management, they can act as champions. Duncan calls this “going where the energy is,” and it’s a great way to build support for institutional change. A good example at MI was the South America Regional office in Lima, which had a fantastic and supportive leadership team. With MI assistance, they began designing and implementing adaptively managed projects that could monitor, course correct, and prove outcomes, and (even better!) proved willing and able to talk about it in public.

There is also opposition from the contractors implementing the projects. This is a simple incentives game:

Afghanistan

contractors don’t want to be judged on outcomes, because they’re afraid they won’t hit them. If they adaptively manage their project and progress along their theory of change and then report that they didn’t achieve their outcomes, that harms their prospects of winning future contracts. We found that it was often difficult to convince contractors to practice adaptive management without being forced to by contract language or USAID management.

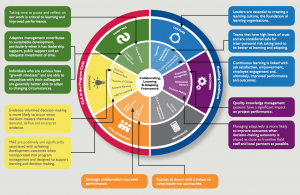

Winning over these stakeholders was a difficult proposition. But doing so is the MI goal: our own outcome. To achieve that, we built the MI theory of change, a massive diagram that faintly resembled the famous Afghanistan spaghetti-mess system analysis.

USAID

One of the solutions we designed was to get adaptive management processes written into the actual guidebooks and project contracts; essentially doing an end-run around the mission staff and implementation teams. From there, we could leverage relationships with champions like South America Regional to teach teams how to design and implement projects according to the new rules and contract language. This relieved us of the task of fighting incentives and appealing to people’s better angels, and allowed us to present ourselves to project teams as people with solutions rather than more problems. One major success of MI was adding a section requiring a theory of change to the ADS Programming Policy series (official USAID guidance on program design and implementation). Another was drafting procurement language mandating adaptive management practices like theory of change workshops, outcome-based reporting, and pause-and-reflect sessions throughout implementation.

During the aforementioned panel event a student asked me, “How do you get people to do good M&E?” It’s a fair question. And I think the answer, more or less, is to approach it like a good adaptive manager. In MI’s case, that meant mapping out the context, identifying the important stakeholders, convincing them, and then using the persuasive power of our mission champions and the coercive power of bureaucratic sanctions to institutionalize the program. And while that is still a distant goal, I think that the process of institutionalization of adaptive management at USAID (or at least our little corner of it) is well on its way.

David Yamron is a former Adaptive Management Specialist for USAID Measuring Impact and a current Master’s candidate in Development Management at the London School of Economics. Check out his new development podcast The World Isn’t Flat, hosted with three other LSE grad students.

Duncan Green's Blog

- Duncan Green's profile

- 13 followers