Review of The Interpreter, Edinburgh & When My Name was Keoko

![[personal profile]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1491408111i/22407843.png) eeoopark

eeoopark

[image error]

[image error]<The Interpreter>

Suki Kim’s debut novel, The Interpreter (2003), revolves around a murder mystery, but offers much more than that. The novel provides a gripping portrayal of interior lives of 1.5 generation immigrant children, who are prematurely brought into the morally ambiguous adult world as interpreters for their non-English speaking parents. Though narrated in the third person, the novel stays close to the psyche of its protagonist Suzy Park, a 29-year-old Korean American woman. In a perpetual state of mourning, she hides from life by drifting from one temporary job to another, and from one married man, Damian, to another, Michael. All that remains of her past is an anonymous person, who keeps sending a bouquet of white irises on the anniversary of her parent’s death.

Though it was Grace, the older sister, who had always been the family interpreter, Suzy realizes that she is cut out for the job of a freelance Korean interpreter. The limited omniscient narrator observes: “The key is to be invisible. She is the only one in the room who hears the truth, a keeper of secrets.” For a moment, it seems like Suzy, an Ivy League drop out and a self-designated “kept woman” has finally found a comfortable niche. However, she is compelled to become not only a keeper but also an investigator of secrets, when she runs into clients who may be connected to the murder of her parents at their vegetable and fruit store.

Loneliness is an emotion that strongly pervades throughout this novel. Though the jaded characters do not shed tears, it is constantly raining in the boroughs of New York and Long Island. Kim’s careful construction of the quiet but roiling emotional terrain of her protagonist Suzy is what makes this book so compelling for me. Despite the plot connected to unsolved murders and missing persons cases taking its time to pick up the pace, I could not put down the book and had to finish it red-eyed. I read The Interpreter during the summer when my goal was to get introduced to a wider range of Korean American fiction. So, I loved that Kim took a nuanced approach to intergenerational and intra-ethnic conflicts depicted in her work.

https://www.amazon.com/Interpreter-Novel-Suki-Kim/dp/0312422245

[image error]

<Edinburgh>

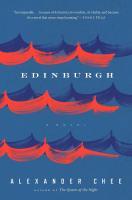

The cover of the reissue edition of Edinburgh by Mariner Books feature blue and red waves painted in rough brush strokes. It is simple, yet mesmerizing. And, when I finally read the lines below, I caught my breath:

“Not blood spilled, but the essence of blood, the red heat, the transaction of all life. A gas passing from one color to the next, blue to red, even the act of breathing a certain alchemy, sure of itself and its result.”

*Spoiler Alert*

The main character of Alexander Chee’s debut novel, Edinburgh (2002), is Aphias “Fee” Zhe, a twelve-year-old boy whose father is of Korean descent and mother, of Scottish descent. Fee has a gifted voice and thus becomes a lead soprano in a boys’ choir in Maine. However, his sexual awakening coincides with his growing awareness of the choir master Big Eric’s victimization of those under his power. This burdens Fee with guilt that follows him through adulthood. Yet, this is not a coming-of-age story of one boy but many, some who do not live on to tell their stories. Fee and those who persist and survive become keepers of those unspoken words. The narrative voice switches halfway through the novel as if Fee is passing on a legacy, which is dark but tinged with possibility of recovery or intergenerational alliance.

Recently, I have read several novels that deal with child molestation that has catastrophic and reverberating effects on all those who are involved such as Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things and Lois Ann Yamanaka’s Blu’s Hanging. This made me contemplate on the jarring contrast created by beautiful prose and controversial content in a work of fiction. As Michael Spinella writes, “if a story about child molestation could ever be beautiful, [Edinburgh] comes very close to that unusual mark.” So, how do we fare as Edinburgh breaks our hearts into little pieces, and later into even tinier pieces? I will not spoil the ending here, but I’ll just say that it left me devastated for a while.

Another element that adds to the lyrical feel of Edinburgh is the recurring image of Lady Tammamo, a fox-spirit created from a blend of East Asian folklore. Chee mixes Japan’s Tamamo no Mae legend with Korea’s legends about Gumiho to create this mysterious figure. He said in an interview, “It was easy for me to imagine [Lady Tammamo] flying through the air and landing on an island off the coast of Korea… She didn’t strike me as the self-destructive type. She struck me as an enormously resourceful character.” Perhaps, it is Fee’s identification with Lady Tammamo, who falls in love with a human, that keeps him from self-destruction and enables him to live on.

<When My Name was Keoko>

I remember reading Linda Sue Park’s A Single Shard (2001) as a teenager. So, it was nice to pick up one of her books again for a light summer reading. Park is most known for her illustration of premodern Korea in her children’s novels. However, the novel I am about to review, When My Name Was Keoko (2002), deals with a more recent past. In author’s note, Park refers to a passage from Korea’s Place in the Sun by Bruce Cumings that kept haunting her: “In the South [of Korea], one particular decade – that between 1935 and 1945 – is an empty cupboard.” And, it is this “empty cupboard” she fills with voices of her characters.

When My Name Was Keoko alternates between the perspectives of two siblings, Sun-hee and Tae-yul, which lends gravity to the escalating conflict in Korea towards the end of Japan’s colonial rule. A war seen from a child’s point-of-view is not as black and white. Therefore, there are moments of surprising tenderness amidst such pain and sorrow.

Sun-hee is ten-years-old and the youngest member of the family. So, the book begins with her complaining about adults who keep secrets from her. Then, she lays out her plans to cleverly uncover those secrets without being noticed. Meanwhile, Tae-yul, almost eighteen-years-old, struggles between his heart’s desires and his duties as the eldest child and the only son of Abuji (“father”). Although the siblings do not remember a time when Korea (or Chosun) was independent, they bear witness to the most brutal period during 35 years of colonial governance. As the title and the cover image foreshadow, their real names are forcibly replaced by Japanese ones (Kaneyama Keoko and Nobuo), Roses of Sharon are uprooted from gardens, and documents printed in hangul are burned. Their coming of age stories are thus inextricable from the history of colonialism.

The most interesting aspect of this bildungsroman / historical fiction is that Sun-hee’s part is narrated in first-person past while Tae-yul’s is narrated in first-person present. I would probably have to think more about how this choice affects the narrative, but it does give each part a distinct tone. Moreover, the clear divide in the narrative alerts the readers to the harshly demarcated roles that these racialized and gendered Korean children must perform as colonized subjects.

Friendship between Sun-hee and Tomo, the son of a Japanese education officer, also stands out as the emotional center of the book. Park builds this relationship with care, and I believe it would not have been as subtle had the characters been slightly older. Tae-yul, for instance, has a crush on a Korean girl his age but does not pursue his romantic feelings as her father is a chin-il-pa collaborating with the imperial government.

One thing I am curious about is how the targeted audience would interpret this book. I am no longer a teenager. Moreover, I read along with the historical hindsight that the young protagonists do not have and therefore, do not elaborate in the book. For instance, when girls aged sixteen years and older are taken away to supposedly work at factories, I know what will become of their fate though both Sun-hee and Tae-yul never find out. In fact, the story of over 200,000 comfort women was unknown to the world until survivors broke their silence in 1991 to demand an apology. On a more personal level, the stories the author learned from her mother, whose name was Keoko, bear striking resemblance with those I heard from my own grandmother who would have been Sun-hee’s age in 1940s. For that reason, this is one of the works that strikes very close to home. When My Name Was Keoko will be interesting to compare with both children’s/YA and adult fiction that cover similar historical events.

comments

comments