Labour is now for the few, not the many

My Times column on the liberal case against the protectionism in the EU customs union:

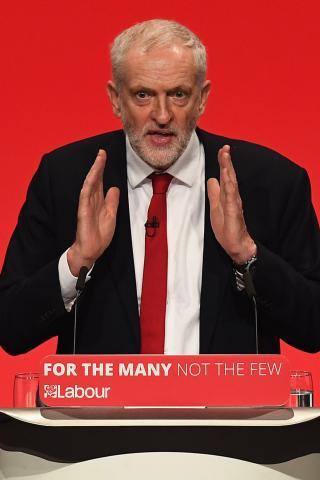

If reports are accurate, there is at least one thing in Jeremy Corbyn’s speech today with which I will agree: “The EU is not the root of all our problems and leaving it will not solve all our problems. Likewise the EU is not the source of all enlightenment and leaving it does not inevitably spell doom for our country. Brexit is what we make of it together.” Yet this makes his overall conclusion, that we should stay in “a” customs union with the European Union, all the more baffling. That would be the worst of all worlds. It would be, in an inversion of the Labour Party’s phrase, “for the few, not the many”.

Mr Corbyn’s proposed customs union would benefit the few, not the manyLEON NEAL/GETTY IMAGES

As Steven Pinker sets out in his new book Enlightenment Now, human beings are cursed by a pervasive negativity bias, “driven by a morbid interest in what can go wrong”. Yet again and again, we defy the pessimists and improve the world. Brexit is fertile ground for this proclivity for pessimism because it has not yet happened. Our imaginations, and those of people with political axes to grind, run riot.

This is being exploited by the paid servants of big business and big government to try to keep us in a customs union system that benefits both. Ordinary people, in my experience, mostly see through this, as they did on referendum day. As a report from the organisations Labour Leave, Economists for Free Trade and Leave Means Leave calculated, the poor would benefit most from Brexit. If the Labour Party is really on the side of the poor rather than the elite, the EU customs union is a curious thing to defend. As David Paton, the professor of industrial economics at Nottingham University Business School, pointed out in a recent paper, The Left-wing Case for Free Trade, free trade always used to be a left-wing cause.

Free trade says to the poorest: we will enable you to get access to the cheapest and best products and services from wherever in the world they come. We will not, in the economist Joan Robinson’s arresting image, put rocks in our own harbours to obstruct arriving cargo ships just because other people put rocks in theirs. The customs union, however, says: if Italy wants rocks in its harbours to protect its rice growers against Asian competition, then Britain must have them too, even though it grows no rice.

Take trainers. Britain makes very few such shoes. It imports lots. The average external EU customs union tariff on them is 17 per cent. Four fifths of this money goes straight to the European Commission. Poor people do not necessarily buy more trainers than rich people but trainers are a higher percentage of their spending. Their inflated trainer prices mean they spend less on other things, which hurts other producers, many of them British, affecting jobs and pay. The tariffs are there for pure protectionism: to aid the shoe industry elsewhere in Europe.

The purpose of all production is consumption, said Adam Smith. Or, as the American wit PJ O’Rourke put it, “imports are Christmas morning; exports are January’s Mastercard bill”. Yet the conversation about the customs union has been conducted almost entirely on behalf of producers, and exporters in particular. Remember, according to the Office for National Statistics in 2016, trade with the EU accounts for only 12 per cent of gross domestic product. It is not unreasonable to put the interests of the other 88 per cent first.

The poor are consumers too. So are businesses, including ones that export. They import raw materials and other goods and the cheaper those are, the more competitive our exporters will be. Outside a customs union, we would not have to cut all tariffs. If we wanted to protect certain British industries then we could, although I hope we would do so sparingly and temporarily.

This argument for free trade is not just a theoretical one. It was demonstrated unambiguously when we flourished after repealing the Corn Laws, which also privileged producers at the expense of consumers, in the mid-19th century. It was demonstrated by the two most free-trading economies in the world, Singapore and Hong Kong, as they roared past us in the prosperity league table from very poor to very rich in recent decades, and more recently by New Zealand and Australia, fast-growing since their turns towards freer trade.

The customs union diverts our trade towards Europe at the expense of poorer countries. The customs union is not a free trade area. It would be possible to be in a free trade area with the EU while outside a customs union, like Iceland, Norway and Liechtenstein.

That we voted to leave the customs union should not be in doubt. The Vote Leave organisation made clear that “Britain lacks the power to strike free trade deals with its trading partners outside Europe. Being in the EU means that Brussels has full control of our trade policy . . . if we vote Leave, we can negotiate for ourselves.” The government made clear that “a common external trade policy is an inherent and inseparable part of a customs union” and that apart from emulating Turkey’s subservient relationship with the EU, “all the alternatives involve leaving the customs union”.

In 1846, two years before the publication of The Communist Manifesto, Richard Cobden, the campaigning manufacturer and politician whose rational optimism has proved a better guide to subsequent history than the conflict-obsessed dialectic of Karl Marx, made a speech in Manchester. “I believe that the physical gain will be the smallest gain to humanity from the success of this principle [free trade],” he said. “I look farther; I see in the free trade principle that which shall act on the moral world as the principle of gravitation in the universe — drawing men together, thrusting aside the antagonism of race, and creed, and language, and uniting us in the bonds of eternal peace.

“I have looked even farther . . . I believe that the desire and the motive for large and mighty empires; for gigantic armies and great navies — for those materials which are used for the destruction of life and the desolation of the rewards of labour — will die away; I believe that such things will cease to be necessary, or to be used, when man becomes one family, and freely exchanges the fruits of his labour with his brother man.”

Give it a try, Jeremy.

Matt Ridley's Blog

- Matt Ridley's profile

- 2180 followers