The scarlet ibis stood about twelve inches high, a

round-backed...

The scarlet ibis stood about twelve inches high, a

round-backed bird with a long black beak and feathers a deep and dusky red. As

if a splash of grapefruit juice was added to the glass of cranberry. The ibis

stood behind a glass case in a museum in Salem, Massachusetts in a room with a

whale jaw hanging from the ceiling, and an interactive wind display – move

the small steering wheel, see the way the movement of air shifts the fine white

sand. The height of the wheel prescribed the intended age of its interactors. A

toddler, three feet high, in checkered over-alls and a knit hat with ear flaps,

twisted the wheel this way, that, back forth, and the fan inside flung the sand

into rippled dunes. The toddler’s father crouched behind him and spoke quietly

in the small boy’s ear. “See it move?” he said. “You’re doing that.”

Nearby, the ibis stood with other birds. A snowy egret, a kingfisher,

lots of finches and warblers, all perched on pins against the wall. They were

stuffed and wired, but the mind didn’t have to work hard to imagine them in

movement, in darty flight or beaking dirt for bugs. A flesh-and-bloodness

remained, a sense of muscle twitch, neck about to stretch, wing about to spread.

Brown polka dots, green flares, a blaze of red on wingtip, a glimmery band of

purple. The staggering variety of life on earth.

Other rooms held famous paintings. The dresses Georgia

O’Keefe wore on her body were on display (there was no muscle movement to be

detected there; they hung flat, shed, dead). A digital exhibit explored four

dimensionality. In a dark space walled by translucent screens, letters were projected

falling and spinning. The effect was like falling through an outer space where stars

were made of alphabet. Chaos, infinity, potential.

The sense of limitlessness neared frightening. The birds

provided a more comprehensible sense of time and place and raised questions

there were answers to. How does the scarlet ibis get that color? Does it absorb

the sunsets? No. It eats prawns. It gulps shrimp and the pigment tints the

feathers. O’Keefe’s paintings are saturated with sunsets, sands, skulls, skies,

petals spreading. Her dresses were black and white. She hasn’t filled them,

hasn’t swished the skirts with her legs, in over thirty years. Who knows when

that ibis swallowed its last shrimp.

All our words and work – our search for food, our

migratory action, our entries, exits, our gathering with others in our

quotidian efforts to keep going, the messages we send to try to make ourselves

understood (I want you, I love you, I’m hungry, I’m scared) – will

be pulverized by time. Our letters and the bones that held us up, stardust. We

try to makesense in the meantime, nagged by a feeling of a promise unkept, something

on offer from the start we’ll never be able to find. We end empty handed,

trying to steer the wind.

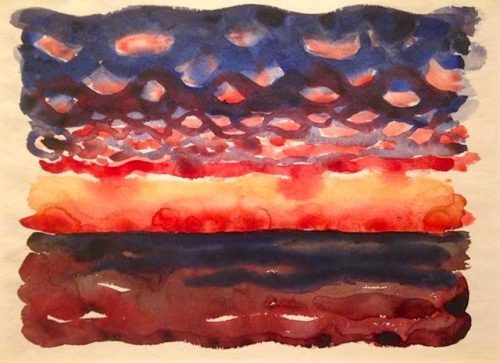

[Georgia O’Keefe, Sunrise and Little Clouds No. II (1916)]