Chant East and West (My Christmas/Epiphany Music, Part 4)

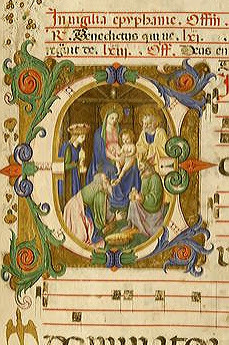

Medieval illuminated chant manuscriptWe are now moving toward the Epiphany/Theophany events and their celebration as the manifestation of the Word made flesh, Jesus Christ, dwelling among us. This gives us a good opportunity to grow in appreciation for that which is called "sacred music" in the primary and eminent sense: the great liturgical chants hallowed by ancient or (at least) long-standing usage in public worship.

Medieval illuminated chant manuscriptWe are now moving toward the Epiphany/Theophany events and their celebration as the manifestation of the Word made flesh, Jesus Christ, dwelling among us. This gives us a good opportunity to grow in appreciation for that which is called "sacred music" in the primary and eminent sense: the great liturgical chants hallowed by ancient or (at least) long-standing usage in public worship.As I have said before, I find beauty in music in diverse and analogous senses, and I appreciate—in the right place, at the right time—good contemporary popular music, jazz, folk and roots music from all over the world, classical music, vocal and instrumental music of all kinds, electronic music, blues and gospel music, etc. All of these ways of crafting sound have their measure of aesthetic excellence, and in their attainment of beauty they are also good and therefore can be edifying.

Some of these forms can be constructed and presented in ways conducive to prayer, and in the appropriate circumstances can contribute to youth gatherings, pilgrimages, prayer meetings, and even parts of the liturgy. It is very moving to see and hear this done well, in a fitting manner, by artists who are themselves people of deep faith and prayer. Unfortunately, it is much more common to find it done badly, carelessly, disjointed from its context. Instead of fostering prayer, it becomes distracting, intrusive, or annoying.

The Lord deserves our best, and there are certainly different ways we can offer that to him in our songs.

But the great ancient chants have endured as liturgical worship music down the centuries for a reason. In them sensible sound draws our complex humanity into simplicity and "silence," and stirs the apex of the soul to prepare us to encounter God. These chants have come forth from prayer and lead back to prayer. They are the fruit of profound communion with God, self-offering, and suffering. They are, so to speak, icons written with sound.

Even in chant, however, there is the concreteness of human expression marked by the history of the great liturgical traditions and the cultures and peoples among whom they arose, our ancestors who continue to be alive within the Communion of Saints.

I can only touch very briefly on these excerpts, and then allow the music to "speak" for itself.

Most familiar to me, of course, is the chant that holds preeminence in the Roman Rite, the most widely used ancient chant of the "Western" liturgical tradition, the Gregorian chant. Pope Saint Gregory the Great (c. 540-604) is the patron of the Roman liturgy.

The traditional Western celebration of the Epiphany focuses on the arrival of the "Magi" from the East to present gifts to the newborn King (as narrated in the beginning of chapter 2 of Matthew's gospel). In these visitors, we can see a symbol of all the nations of the earth, and thus the nations are represented as "present" at the beginning of Christ's coming into the world.

Listen here to the noble simplicity of Gregorian chant in this recorded (and visual) presentation of the Vidimus Stellam, the Gospel Acclamation that immediately precedes the reading (or chanting) of the Gospel for the Mass of the Epiphany in the Roman Rite: "Alleluia. We have seen his star in the East, and we have come with our gifts, to adore the Lord."

Take a moment to lift up your mind and heart to God. We are not in a hurry.

Take some time.

We can perceive in this chant something of the spirit of the monastic life in its gentle rhythm, great peace, interior focus, and the seeking of God and the finding of him in adoration and worship. For well over a millennium and still today, monasteries have prayed using Gregorian chant in different degrees, manners, and adaptations.

But it's not only for monasteries.

The verse above, of course, is primarily intended for a single voice (the cantor), and many chants in public Mass settings are sung by a small, trained choir. Nevertheless much Gregorian chant (especially chant of the basic prayers of the Roman liturgy) is accessible to congregational singing, with a little pastoral initiative, attention, and effort. It's an effort worth making.

Meanwhile, although the Western liturgical tradition is the most widely diffused throughout the world, it is not the only tradition. Let us take time to look to the East.

The Byzantine liturgical tradition has Saint John Chrysostom (c. 347-407) as its primary patron. The high point of the Christmas season in the Byzantine tradition is the celebration of the Theophany on January 6th (which corresponds to the Western traditional feast of "The Baptism of the Lord" on the Sunday following January 6th).

Here the focus is entirely on Christ's baptism in the Jordan river as a corollary event to his birth. The revelation of the Trinity in the Spirit descending in the appearance of a dove, the Father's voice, and the flesh of the Word plunged into the river radically "consecrates" all the waters of the world and establishes the foundation for the sacrament of baptism, the new birth of the Christian in Christ.

Byzantine chant has great solemnity and also various styles, as we shall hear by way of a small example. First, here is the "Theophany Hymn" chanted in Greek: All you that in Christ have been baptized have put on Christ, Alleluia. This beautiful hymn is accompanied in this video by a fine visual presentation of different icons. Listen and watch here:

Take some silent time if you wish.

When the Byzantine tradition moved beyond the Greek speaking Eastern Roman Empire later in the first millennium, it both shaped and was shaped by the distinctive peoples and languages of the Slavic world. A different style emerged within the Byzantine rite, expressed in a different language that can still be heard today, that has become known as Church Slavonic.

This video presents a different verse from the same Byzantine liturgy for the feast of the Theophany, in a different language (though here I think it is Russian rather than Church Slavonic). Listen to the very distinctive beautiful style of the old Slavonic chant:

What tremendous music this is.

I'm putting these various links here, but please take your time. Come back to these links whenever you want, or go on YouTube to listen to more, or take a course on sacred music, join your parish choir, or go on a retreat, go pray.

************

Welcome back.

We're going to take a turn to something very different in sound and language from what we have heard in the Latin, Greek, and Slavic traditions. Ironically, however, this ancient chant may be closer to the musical style and language of Jesus himself and his first apostles and disciples.

The Copic liturgical tradition is one of the ancient Semitic traditions that endures to this day, from the church of Alexandria in Egypt which has Saint Mark the Evangelist as its patron. Here again, we are celebrating the Epiphany, in a style and language that sounds like Arabic but is in fact the language that predates the Muslim conquest of Egypt and the Middle East. The chant of Psalm 150 is fittingly accompanied by cymbals (see 150:5).

The sacred music of the "ancient Near East" is also the sacred music of people today who worship Christ under dangerous circumstances, under the constant threat of violence. This is the song and music of people who have very recently shed their blood in the name of Jesus, and who will courageously face that danger again this weekend when they gather to celebrate Epiphany and sing this song:

So we have these profound "sonic icons" through which our ears are opened and our hearts lifted to the glory of God and his angels and all the saints. Music in these modes was handed down through the centuries, modified only with the greatest care.

************

But then what happened?

[Permit me to have a bit of "fun" here?

Published on January 03, 2018 20:53

No comments have been added yet.