Movies I Watched in October, Part 2

Part two of the October Movie Watching trilogy...

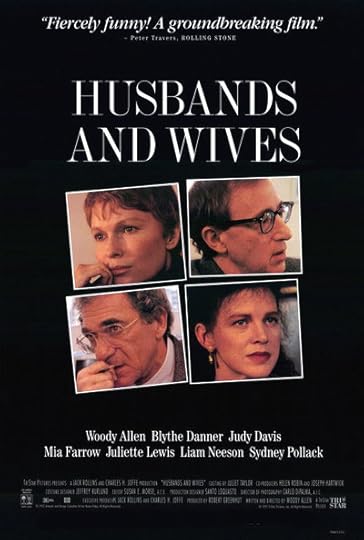

It feels a little strange to be writing about a Woody Allen movie – and arguably his most controversial one – in the sociopolitical current climate, but hey, I watch what I watch and I write what I write. This is probably Allen's last really solid movie following his outstanding 1980s run (including “Stardust Memories,” “Zelig,” “Broadway Danny Rose,” “Purple Rose of Cairo,” “Hannah and Her Sisters,” “Radio Days” and “Crimes and Misdemeanors”) and it’s an especially interesting film to watch now. For one thing, when "Husbands and Wives" was released in 1992, it was right after the news that Allen had been having an affair with Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter broke, which gave the divorce plot of “Husbands and Wives” a whole other level to be dissected. Because of that, the movie probably wasn’t appreciated for what it actually was, a well-made, small scale drama about how relationships live, die and (sometimes, though not always) bring themselves back to life. Allen and Farrow (in her last film with him – wonder why?) play a typical rich, intellectual New York couple stunned to hear their best friends (Sydney Pollack and Judy Davis) are splitting up. This leads them to question their own marriage, and it leads all of them to pursue (or at least consider pursuing) relationships with other rich, intellectual New Yorkers, including a post-“Darkman,” pre-“Schindler” Liam Neeson and a post-“Cape Fear,” pre-“Natural Born Killers” Juliette Lewis. Allen’s flirtation with Lewis is the most, er, problematic thing about the movie, partly because it seems so forced, and partly because, though Lewis is implied to be a few years older than Mariel Hemingway was in Manhattan, Allen is 13 years older and, frankly, looks it. On the other hand, Pollack and Davis are the best things about the movie, delivering energetic and angry performances that feel a lot more lively than Allen and Farrow. (I can't stress how much I like Pollack as an actor -- in this, "Tootsie," "Michael Clayton," "Eyes Wide Shut," you name it.) By the end of the movie, you barely care about Allen and Farrow’s relationship and whether it does or doesn’t survive, but you do care about Pollack and Davis – the whole movie should’ve been about them. One more thing that struck me about this movie, and about a lot of Woody Allen movies, come to think of it: Though he’s praised for his characters and dialogue (and he’s done great work with both, don’t get me wrong), watching “Husbands and Wives” it hit me that, for most of the movie, I didn’t believe these characters as actual people. It started to drive me crazy when they’d drop the name of some author or say something like “I have tickets to the opera” – it just didn’t feel anything like how actual people – even actual rich, intellectual New York people – act. It all felt, frankly, like placeholder dialogue that was designed to be replaced by something sharper and better. Maybe that’s why people prefer Woody Allen’s earlier, funnier movies – because they actually had some work put into them, including more than one draft of a script. I still like many of Allen’s films, including this one, but it’s easy to see why – scandals and controversy aside – many people don’t.

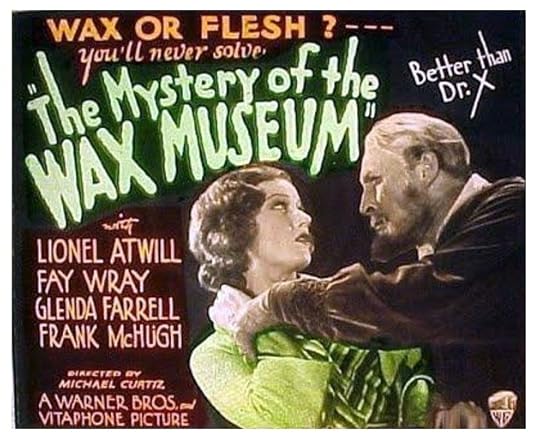

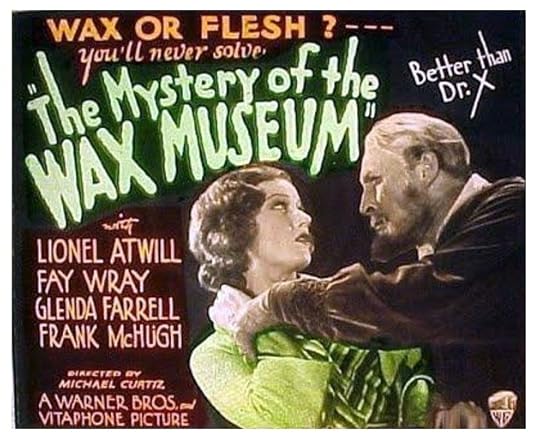

I love the Universal horror movies with their indeterminate, quasi-European settings and hard-to-pin-down time periods, but there’s something wonderfully weird about the few horror movies Warner Bros. produced in the early 1930s. That's mostly because they attempted to add the elements the studio was known for – newsroom settings, modern crimes and fast-talking dames – to lurid, even gruesome, horror elements. Even better, two of them – “Doctor X” and “Mystery of the Wax Museum” – were filmed using the two-strip technicolor process, giving them a dreamlike look that only adds to their oddball charm. TCM (who else?) included “Mystery of the Wax Museum” in its Halloween programming, so I made sure to catch it in its entirety, and wow, was I not disappointed. Glenda Farrell stars as a tough-talking reporter looking for a big scoop, and she figures she’s stumbled onto something involving the wax museum that opened on New Year’s Day. It’s owner and artistic director, played by the always welcome (and always creepy) Lionel Atwill, was horribly burned by gangsters years ago, and now he splits his time between plotting revenge and obsessing over his wax figure of Marie Antoinette. Enter Fay Wray, who is (Coincidentally? Naturally?) the spitting image of Marie, and from there things go deliciously insane. All the elements – the strange colors, the 1930s sensibilities, the dark humor and the even darker horror – add up to a movie that’s rarely actually scary but also never not fun. Keep an eye out during the scenes set in the wax museum – wax figures would’ve melted under the insanely hot studio lights required for two-strip color, so those are human extras trying (and often failing) to remain perfectly still.

I love the Universal horror movies with their indeterminate, quasi-European settings and hard-to-pin-down time periods, but there’s something wonderfully weird about the few horror movies Warner Bros. produced in the early 1930s. That's mostly because they attempted to add the elements the studio was known for – newsroom settings, modern crimes and fast-talking dames – to lurid, even gruesome, horror elements. Even better, two of them – “Doctor X” and “Mystery of the Wax Museum” – were filmed using the two-strip technicolor process, giving them a dreamlike look that only adds to their oddball charm. TCM (who else?) included “Mystery of the Wax Museum” in its Halloween programming, so I made sure to catch it in its entirety, and wow, was I not disappointed. Glenda Farrell stars as a tough-talking reporter looking for a big scoop, and she figures she’s stumbled onto something involving the wax museum that opened on New Year’s Day. It’s owner and artistic director, played by the always welcome (and always creepy) Lionel Atwill, was horribly burned by gangsters years ago, and now he splits his time between plotting revenge and obsessing over his wax figure of Marie Antoinette. Enter Fay Wray, who is (Coincidentally? Naturally?) the spitting image of Marie, and from there things go deliciously insane. All the elements – the strange colors, the 1930s sensibilities, the dark humor and the even darker horror – add up to a movie that’s rarely actually scary but also never not fun. Keep an eye out during the scenes set in the wax museum – wax figures would’ve melted under the insanely hot studio lights required for two-strip color, so those are human extras trying (and often failing) to remain perfectly still.

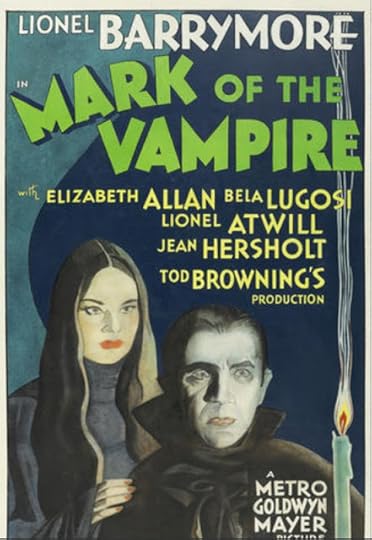

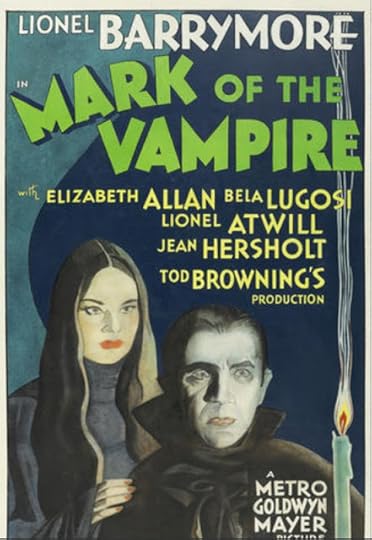

And, proving that not every horror made in the 1930s was a classic, we come to “Mark of the Vampire,” a 1935 film that I’ve read about in dozens of books (the photos of Carroll Borland are downright iconic) but somehow managed to never see, despite the fact that I’ve owned a nice DVD copy for more than a decade. It’s a semi-remake of the 1927 Lon Chaney movie “London After Midnight,” also directed by Tod Browning. I’ve never seen that one either (it’s considered lost and only exists as a series of stills), but part of the problem of “Vampire” lies in its roots to that earlier film. Quick history lesson: Before Browning’s “Dracula” hit theaters in 1931, virtually every American horror movie cheated on the actual “horror” by revealing supposedly supernatural events to be hoaxes perpetrated to achieve some far-fetched goal (often involving an inheritance). One reason “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” had such a seismic impact was they deal with actual monsters. That’s why “Mark of the Vampire” is so frustrating (spoilers coming up for an 82-year-old film): The convoluted, creaky plot involving Lugosi and Borland supposedly being vampires is revealed to be nothing but a scam -- they’re really a couple of stage actors hired to trick the real murderer into confessing his crime. It feels like a cheat (because it is one), and what’s more, it wastes the skills of Lugosi (who gets just one line of dialogue at the end of the film) and Borland (who, like I said, is an iconic vision that launched a million goth girls). Browning’s direction, as per usual for his later works, is creaky and stagy, but legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe does manage to give the movie an ominous, shadowy style that, like the other intriguing elements, winds up being wasted. If you’re bound and determined to watch ever last 1930s horror film (like I was), I suppose you should check this out – but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Up next: More Lugosi -- in a pair of offbeat RKO comedies -- plus possibly the greatest horror comedy ever made (at least in this guy's opinion)

It feels a little strange to be writing about a Woody Allen movie – and arguably his most controversial one – in the sociopolitical current climate, but hey, I watch what I watch and I write what I write. This is probably Allen's last really solid movie following his outstanding 1980s run (including “Stardust Memories,” “Zelig,” “Broadway Danny Rose,” “Purple Rose of Cairo,” “Hannah and Her Sisters,” “Radio Days” and “Crimes and Misdemeanors”) and it’s an especially interesting film to watch now. For one thing, when "Husbands and Wives" was released in 1992, it was right after the news that Allen had been having an affair with Mia Farrow’s adopted daughter broke, which gave the divorce plot of “Husbands and Wives” a whole other level to be dissected. Because of that, the movie probably wasn’t appreciated for what it actually was, a well-made, small scale drama about how relationships live, die and (sometimes, though not always) bring themselves back to life. Allen and Farrow (in her last film with him – wonder why?) play a typical rich, intellectual New York couple stunned to hear their best friends (Sydney Pollack and Judy Davis) are splitting up. This leads them to question their own marriage, and it leads all of them to pursue (or at least consider pursuing) relationships with other rich, intellectual New Yorkers, including a post-“Darkman,” pre-“Schindler” Liam Neeson and a post-“Cape Fear,” pre-“Natural Born Killers” Juliette Lewis. Allen’s flirtation with Lewis is the most, er, problematic thing about the movie, partly because it seems so forced, and partly because, though Lewis is implied to be a few years older than Mariel Hemingway was in Manhattan, Allen is 13 years older and, frankly, looks it. On the other hand, Pollack and Davis are the best things about the movie, delivering energetic and angry performances that feel a lot more lively than Allen and Farrow. (I can't stress how much I like Pollack as an actor -- in this, "Tootsie," "Michael Clayton," "Eyes Wide Shut," you name it.) By the end of the movie, you barely care about Allen and Farrow’s relationship and whether it does or doesn’t survive, but you do care about Pollack and Davis – the whole movie should’ve been about them. One more thing that struck me about this movie, and about a lot of Woody Allen movies, come to think of it: Though he’s praised for his characters and dialogue (and he’s done great work with both, don’t get me wrong), watching “Husbands and Wives” it hit me that, for most of the movie, I didn’t believe these characters as actual people. It started to drive me crazy when they’d drop the name of some author or say something like “I have tickets to the opera” – it just didn’t feel anything like how actual people – even actual rich, intellectual New York people – act. It all felt, frankly, like placeholder dialogue that was designed to be replaced by something sharper and better. Maybe that’s why people prefer Woody Allen’s earlier, funnier movies – because they actually had some work put into them, including more than one draft of a script. I still like many of Allen’s films, including this one, but it’s easy to see why – scandals and controversy aside – many people don’t.

I love the Universal horror movies with their indeterminate, quasi-European settings and hard-to-pin-down time periods, but there’s something wonderfully weird about the few horror movies Warner Bros. produced in the early 1930s. That's mostly because they attempted to add the elements the studio was known for – newsroom settings, modern crimes and fast-talking dames – to lurid, even gruesome, horror elements. Even better, two of them – “Doctor X” and “Mystery of the Wax Museum” – were filmed using the two-strip technicolor process, giving them a dreamlike look that only adds to their oddball charm. TCM (who else?) included “Mystery of the Wax Museum” in its Halloween programming, so I made sure to catch it in its entirety, and wow, was I not disappointed. Glenda Farrell stars as a tough-talking reporter looking for a big scoop, and she figures she’s stumbled onto something involving the wax museum that opened on New Year’s Day. It’s owner and artistic director, played by the always welcome (and always creepy) Lionel Atwill, was horribly burned by gangsters years ago, and now he splits his time between plotting revenge and obsessing over his wax figure of Marie Antoinette. Enter Fay Wray, who is (Coincidentally? Naturally?) the spitting image of Marie, and from there things go deliciously insane. All the elements – the strange colors, the 1930s sensibilities, the dark humor and the even darker horror – add up to a movie that’s rarely actually scary but also never not fun. Keep an eye out during the scenes set in the wax museum – wax figures would’ve melted under the insanely hot studio lights required for two-strip color, so those are human extras trying (and often failing) to remain perfectly still.

I love the Universal horror movies with their indeterminate, quasi-European settings and hard-to-pin-down time periods, but there’s something wonderfully weird about the few horror movies Warner Bros. produced in the early 1930s. That's mostly because they attempted to add the elements the studio was known for – newsroom settings, modern crimes and fast-talking dames – to lurid, even gruesome, horror elements. Even better, two of them – “Doctor X” and “Mystery of the Wax Museum” – were filmed using the two-strip technicolor process, giving them a dreamlike look that only adds to their oddball charm. TCM (who else?) included “Mystery of the Wax Museum” in its Halloween programming, so I made sure to catch it in its entirety, and wow, was I not disappointed. Glenda Farrell stars as a tough-talking reporter looking for a big scoop, and she figures she’s stumbled onto something involving the wax museum that opened on New Year’s Day. It’s owner and artistic director, played by the always welcome (and always creepy) Lionel Atwill, was horribly burned by gangsters years ago, and now he splits his time between plotting revenge and obsessing over his wax figure of Marie Antoinette. Enter Fay Wray, who is (Coincidentally? Naturally?) the spitting image of Marie, and from there things go deliciously insane. All the elements – the strange colors, the 1930s sensibilities, the dark humor and the even darker horror – add up to a movie that’s rarely actually scary but also never not fun. Keep an eye out during the scenes set in the wax museum – wax figures would’ve melted under the insanely hot studio lights required for two-strip color, so those are human extras trying (and often failing) to remain perfectly still.

And, proving that not every horror made in the 1930s was a classic, we come to “Mark of the Vampire,” a 1935 film that I’ve read about in dozens of books (the photos of Carroll Borland are downright iconic) but somehow managed to never see, despite the fact that I’ve owned a nice DVD copy for more than a decade. It’s a semi-remake of the 1927 Lon Chaney movie “London After Midnight,” also directed by Tod Browning. I’ve never seen that one either (it’s considered lost and only exists as a series of stills), but part of the problem of “Vampire” lies in its roots to that earlier film. Quick history lesson: Before Browning’s “Dracula” hit theaters in 1931, virtually every American horror movie cheated on the actual “horror” by revealing supposedly supernatural events to be hoaxes perpetrated to achieve some far-fetched goal (often involving an inheritance). One reason “Dracula” and “Frankenstein” had such a seismic impact was they deal with actual monsters. That’s why “Mark of the Vampire” is so frustrating (spoilers coming up for an 82-year-old film): The convoluted, creaky plot involving Lugosi and Borland supposedly being vampires is revealed to be nothing but a scam -- they’re really a couple of stage actors hired to trick the real murderer into confessing his crime. It feels like a cheat (because it is one), and what’s more, it wastes the skills of Lugosi (who gets just one line of dialogue at the end of the film) and Borland (who, like I said, is an iconic vision that launched a million goth girls). Browning’s direction, as per usual for his later works, is creaky and stagy, but legendary cinematographer James Wong Howe does manage to give the movie an ominous, shadowy style that, like the other intriguing elements, winds up being wasted. If you’re bound and determined to watch ever last 1930s horror film (like I was), I suppose you should check this out – but don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Up next: More Lugosi -- in a pair of offbeat RKO comedies -- plus possibly the greatest horror comedy ever made (at least in this guy's opinion)

Published on November 15, 2017 17:06

No comments have been added yet.

Will Pfeifer's Blog

- Will Pfeifer's profile

- 23 followers

Will Pfeifer isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.