Every Day is Veterans Day

Betty Skinner never forgot.

She never forgot their smiles.

She never forgot their long talks.

She never forgot their love.

And she never forgot their Army green duffel bags, standing in the hallway, where her father and brother once stood.

When Betty turned fifteen, rumors of imminent war were clouding the horizon. Her father, Colonel Russell Walthour, was called to active duty, so he moved his family to Union, South Carolina, where he was put in command of an infantry division. He became so devoted to the troops in his division that when the governor of Alabama offered him a promotion, he turned it down because it meant he would have to leave his men and sit behind a desk in Montgomery.

Within two years, her father’s battalion was transferred to Colorado, and soon after he was sent off to war. The commander of a battalion on the European front had been killed, and the army ordered Colonel Walthour to take over immediately. He had to abruptly leave his men and family to go directly into one of the last and bloodiest conflicts of World War II—the Battle of the Bulge.

Seventy-five thousand troops were lost that savage winter, and Colonel Walthour stood day after day watching young men collapse into their deathbeds of bloody snow.

In the summer when she was nineteen, Betty’s father returned to them unexpectedly. The army said he was suffering from battle fatigue and had sent him to one of the huge Miami Beach hotels that had been converted into military hospitals. In early June, they allowed him to come home for a family visit. Her mother quickly saw that something was very wrong. Colonel Walthour was acting strangely and incessantly paced around the dining room table muttering softly and fretfully swinging his gold pocket watch. She became so worried about his bizarre behavior that she hid their old shotgun behind the cabinet in the garage and asked the army to send him back to the hospital early—which they did.

“One hot day in July, I was upstairs at my desk when I heard the doorbell ring. I opened the door and two army officers in dress uniforms asked to see my mother. I offered them a seat on the blue velvet settee in our parlor and went to the kitchen to find her. Mama came out and thanked the officers but she showed no reaction to the telegram that they handed her. It was the standard War Department one received by so many other families in those days. ‘The War Department regrets to inform you . . .’

“After the men left, Mama just sat on the couch, so I went back upstairs to my room feeling a strange, vague numbness. Mama didn’t tell me what was in the telegram, but somehow I knew that Daddy was dead. It would be years later before I found out that he had hanged himself with his belt from a rafter in his hospital room. The raw truth of his suicide was never discussed. Suicide was not something you discussed in polite company.”

The army report said that Russell had had a nervous breakdown two years earlier, while serving on the front line. He had gone up to check on his men, being very careful to leave his jeep and driver in what he thought was a safe place, but when he returned he found only the smoldering remains of his vehicle and his young driver blown apart by an artillery shell. It proved to be more than Russell could bear.

“I wasn’t prepared for my father’s death. My world as a child had been far removed from the brutalities of reality. Pain struck deeply for the first time and I didn’t know what to do with it. We had been taught to ‘keep a stiff upper lip.’ Feelings and emotions were suppressed, never expressed. Yet on that pain-filled day in July, for the very first time, a vague intuitive sense of reality awakened within me. It shadowed me like a mist on a gray day. I couldn’t see through it, but I knew it was there—and it never left me.

“Daddy’s funeral at Arlington National Cemetery was impressive and befitting his rank. Beautiful horses pulled the caisson bearing his flag-draped casket. There was an honor guard and the twenty-one-gun salute, followed by a bugler playing taps. Mama was quiet; I remember that she didn’t cry or hug me. We never spoke of Daddy again.”

In 1950, Betty’s younger brother, Charlie, was sent away to fight in the Korean War. They were very close because both were reserved and quiet and had always been able to understand each other. Betty was so proud of him. He was tall and handsome and gentle like her father and a natural leader, graduating at the top of his class at Virginia Military Institute. She felt safe with him. They had shared a lifetime of quiet heart connection, living through so much of the same pain, change, and loss together. Because she was so naive, she wasn’t at all concerned for his safety. It never occurred to her that young men might die again so soon after World War II.

After all, Korea was such a small war in such a small country so far away.

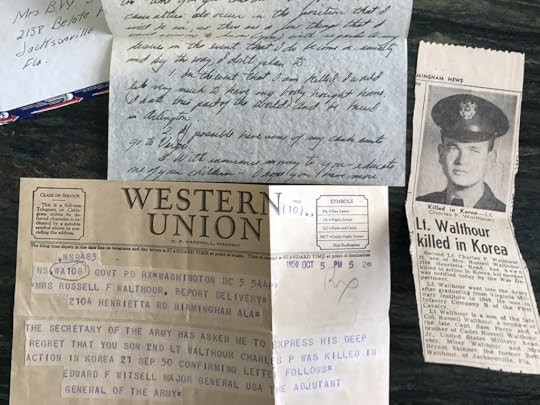

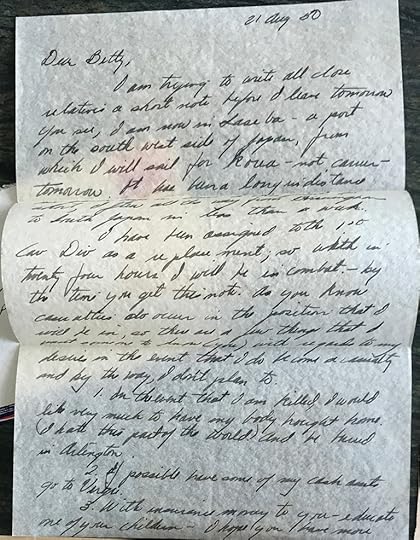

She was thrilled when she finally found a letter from him in the mailbox, but her heart sank as her eyes skimmed quickly across the pages. Charlie sounded terribly depressed as he wrote about the horrors of war and the “God forsaken” place he was in. He asked her to promise him three things if anything happened to him: first, she was not to let them leave his body in Korea; second, she was to use his $5,000 government insurance policy to educate her children; and third, she was to make sure that any other money of his went to Virgie, their old housekeeper. It sounded like a premonition of death, which frightened her and triggered a pain so deep she wasn’t able to hold it. She carefully put the letter in the desk drawer beside her bed, repressed the flood of surfacing emotion, and put the fear out of her mind.

About two months later she got the phone call from her mother that at some unconscious level she had been waiting for. Her mother very calmly told Betty that she had some bad news. She had received another telegram from the War Department informing her that Charlie had been killed in action. A single bullet had penetrated the zipper of his flak jacket and exploded in his chest. The ponderous silence that surrounded her father’s suicide had weighed so heavily on Betty’s memory and feelings that she repressed all emotion when the news of Charlie’s death came. All she knew to do was what she had learned from her mother, so she stuffed the overwhelming pain deep into her soul and went on with her busy life. As with her father, her brother was never spoken of again. She never dealt with his loss, never cried a tear. She just didn’t think about it.

She never forgot, either.

After both her father and brother died, their duffel bags were sent home. They stood there near the front door, dull, upright, with shoulder strap that closed with a pull at top.

Her mother never opened them, and when the family headed back south, the unopened bags went with them.

Ask Betty today what she remembers of both her father’s and her brother’s deaths, and she’ll tell you about the duffel bags—standard issued stand-ins for a father and brother that were everything but standard issued. She’ll also tell you about her love for her father and her brother, the love they shared, and the pain they felt.

There is one day on the calendar to honor deceased veterans, and another day to honor and thank all others veterans for their service. For Betty, and the generations of children that followed in her footsteps, barely a day passes, even now, when she doesn’t think of her father and her brother, of their service, and of the loss. There’s no one or two days. Every day is Veterans Day.

Charlie Walthour’s letter to his sister Betty, dated exactly one month to the date he was killed in action.

Charlie Walthour’s letter to his sister Betty, dated exactly one month to the date he was killed in action.