Michael Faraday: Read ~ and watch! ~ this, not that, about the scientific method!

Do you know this “eat this, not that” series of books? The idea is to help you make good choices in food and drink to avoid hidden calories that will tank your health. Well, Rosie had the thought that we could do something similar with books for the Library Project*.

The Chemical History of a Candle ~ Lectures by Michael Faraday

(This is not an affiliate or promotional post, other than, as usual, the Amazon links. I am simply passing along to you some exciting resources for your curriculum and enjoyment. Anyway, it can all be accessed for free!)

I will tell you a different, more effective and enjoyable, way to begin formal scientific study: by learning about how a candle works — but not only a candle! By studying the lectures of Michael Faraday, the child will learn about human respiration and about how one learns about and tests ideas in the world — the scientific method!

You could just pull out a dry textbook with the steps of each thing — burning candle, human respiration, scientific method — and drum each step into your child’s head. No doubt there will be boredom, tears, bitterness, recalcitrance, and in the end, either learning the material or… not learning it. There would definitely be no wonder and no joy. I think that nothing has hurt science more in our time than the way we teach it…

There is another way, before you get to that miserable workbook existence, which is to let things unfold by simply observing, along with a master teacher, seemingly ordinary processes that, with careful thought, will yield their mysteries… if we are patient.

How did I find out about this book? I’ll tell you if you don’t mind a long story…

God has given me what seems to be a unique ability (at least, I don’t see others being so silly) to stumble around with a strong opinion, trying to put it into practice in an unsatisfactory way, sometimes questioning whether in fact I am right, but not being super motivated to do things the normal way, and then only later, far later, discovering that someone has figured it all out much better and has definitely confirmed my bias.

I would say that this ability is a dubious one, but who am I to question Him. The upside is that I can write about it after the fact! The downside is… my poor children…

So it was that, having studied a lot of science in high school in the approved manner, I came to the homeschooling of my own children with a skepticism — a strong opinion, that is — as to the methods, philosophy, pedagogy, and, frankly, efficiency of the way science is taught.

I have recommended the writings of Arthur Robinson here before. Robinson is a world-class scientist whose homeschooled children have gone on to excel in science — and that is the sort of expert I like! Too often we are getting advice from sources that only repackage the mediocre methods of the conventional education system, slapping the “homeschool” label on it but not showing any results. Robinson rejects this process, and I’ll let you go ahead and read his reasons for yourself. To me they are convincing.

I actually emailed his foundation about 13 years ago to find out what he recommends as curriculum for the years before the child is ready to tackle college physics, chemistry, and biology (in that order, by the way — completely contrary to how it’s done in most high schools). The answer* amounted to having your child learn to be serious about observation and to do a lot of reading in the history of science, including the Faraday Lectures.

*At the end of the post I will let you know what Arnold Jagt, the man I corresponded with, shared about their book list.

I can’t say I did very well by my children on all this, true to form (see above, my “special gift”). I did try, but there’s only so much one person can do, I find, and you have to remember that for most of the time I was homeschooling, the internet was either not a thing or not as easily searchable as it is today!

But the Chief and I did read The Chemical History of a Candle — lectures by Michael Faraday, at the dinner table when our younger children were a bit older — specifically with our William, who early on showed that he really does have an interest in scientific matters. He was in middle school, Bridget was just a kid, and I think Deirdre sometimes took part (she would have been about 16 or 17).

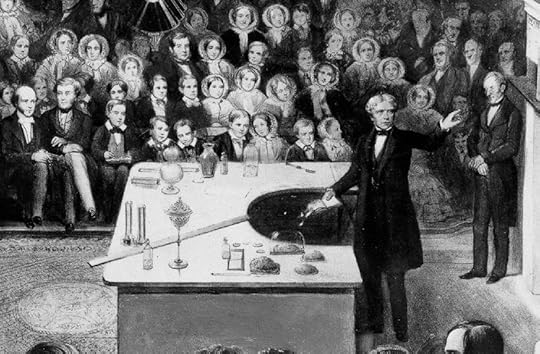

It’s not an easy book to read in our day, although, gulp, it was delivered as lectures for young people (note their presence, along with that of many women, in the image at the top of the page!). The Victorian diction takes getting used to! We did our best, and I am proud to say that there was an actual candle lit, as is our custom at dinner, while we read and talked about the ideas.

Somehow I stumbled across this series of videos which I am sure will be of tremendous help to all. I can’t believe how lucky you all are to have them! So that is why I am writing this post — at last, this half-baked idea/execution of mine is in a form that others can actually use.

Here is the first video, and the others will pull up when you play it — all five of Faraday’s lectures:

This version has commentary from the producers:

You can buy companion volumes from these fellows, or of course you can buy on Amazon (again, my Amazon link is an affiliate link — a small amount of your purchase goes to me, thanks! — but I am not connected with engineerguy.com nor do I get anything for telling you about all this). You can also download the book and study guides for free by going to their site. I can definitely see the value of having hard copies, and they certainly deserve some support for all this content!

I recommend that you read the book yourself first. If your student is at least middle-school-aged, have him read it as well — let him wrestle with it a little bit! Then watch the video together. It may work just fine for the student to watch the video with commentary after that.

Look over the student guides and see how much of it, especially at the beginning, you can achieve just with ordinary discussion with your normal candle lit on the table! Candles are so beautiful.

A lot of the discussion arises just from looking at them. The more natural you can make the conversation, the better for the ultimate purpose of the whole thing, which is to be in the habit of musing on what we see — not pedantically reducing the moment to a series of tedious Q & As, just because that’s how they happen to be written out in the guide.

For instance, it’s fine to say something like “that flame has so many colors in it! I wonder how many we can actually identify!” and see what your child says about it, rather than asking the questions in the order and manner that they are listed. It’s so helpful to have the guide — I would use it as just that, a guide!

As you can see from the activities, some you could do with a very young child, like seeing how many drops of water you can get onto a penny. It’s good to know that a younger child would be interested to take part in this demonstration — and that at the very same time, one could also muse with John Henry Newman on capillary action and how it relates to other laws of nature (Discourse 3, The Idea of a University: Bearing of Theology on other Branches of Knowledge):

Again, did I know nothing about the movement of bodies, except what the theory of gravitation supplies, were I simply absorbed in that theory so as to make it measure all motion on earth and in the sky, I should indeed come to many right conclusions, I should hit off many important facts, ascertain many existing relations, and correct many popular errors: I should scout and ridicule with great success the old notion, that light bodies flew up and heavy bodies fell down; but I should go on with equal confidence to deny the phenomenon of capillary attraction. Here I should be wrong, but only because I carried out my science irrespectively of other sciences.

So there are many things to be learned, aren’t there — just by observing a candle!

This series could be a good chunk of your middle-school science year, in my opinion! See what you think!

*Here are some of the recommendations given to me from the Robinson Curriculum:

For very young children, the books of Arthur Scott Bailey, which you can upload to your Kindle and read aloud, or find secondhand. (I would avoid the paperback versions I see on Amazon that have dreadful fonts, like the Tale of Jolly Robin. Some of them are published by Dover Children’s Thrift Classics. I’m not sure how much of this sort of thing most children can take. Ambleside has more varied recommendations as well.)

The “Tom Swift and his — ” (Motorcycle, Motorboat, Airship, etc) books. (I gather that the basic idea is motivation to do lots of things with motors, rather than viewing them as black boxes for grownups.)

For older children, Common Sense of the Exact Sciences, by W. K. Clifford. (Maybe the engineering guys could do a video series on this one! Also the next one… ) Of the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals by William Harvey. (Harvey was immensely important to the study of medicine. Before his time, doctors relied on arguments from authority — if the ancients said it, that was good enough for them. No doubt the ancients were working on what they could observe, but one must keep observing! It’s not good enough to regard information as a closed book, and of course, Harvey was greatly aided by the development of lenses, however rudimentary. Studying him along with Faraday is important for understanding the scientific method, as well as for removing preconceptions about how modern that method is; Harvey was practicing medicine in the very early 1600s).

And here is a list of the Royal Institution Christmas Lectures of which Faraday’s were a part.

*What is the Like Mother, Like Daughter Library Project?

The post Michael Faraday: Read ~ and watch! ~ this, not that, about the scientific method! appeared first on Like Mother Like Daughter.