It's Never Gone with the Wind...

Please take the following as an addendum to my post from three years ago called The Goddam Movies. I said pretty much all I wanted to say there on the subject of film’s adverse effect on our culture, especially in regards to racial attitudes. But two things happened this past week that prompt me to go back to the subject. The first was that I re-watched one of my Personal Top 100 Favorites (blog post to come)—His Girl Friday—for perhaps the 6thor 7th time. Delightful as ever…with a few sobering notes. One is that Earl Williams the convicted man whose hanging Cary Grant’s Walter wants Rosalind Russell’s Hildy to cover was accused of killing a “colored” cop. Use of the word “colored” for blacks was pretty standard at the time, so nothing surprising there. It was a little ironic however given our current climate that a white man would be hanged for killing a black cop. And the backstory to that is interesting in itself. It seems the mayor is running for re-election and is pushing for the white guy’s execution to assure he gets the black vote. It’s like a bizarro version of 21st century America. But what really pricked my ears was hearing a throwaway line about a “colored” woman giving birth to “a pickaninny” in the back of a cab. For all the times I’d seen the film, that line had clearly passed under my awareness, though I knew instantly this time that if used in a contemporary film it would unleash a world of controversy. Student for life that I am, I immediately researched the word. It is derived from the Portuguese word pequeno for “little”. Derivations of it apply worldwide (probably wherever Portuguese explorers/colonists roamed) to babies and children, particularly those of color. How, where, and when it became a racial slur seems a little unclear, though it is clearly regarded as one today (but as we’ve seen, those things can change).

Anyway the day after re-watching His Girl Friday with my racial antenna still turned on, I came upon an article entitled How Movie Theaters, TV Networks, and Classrooms Are Changing the Way They Show Gone With the Wind: After almost 80 years, America is finally rethinking how it screens its favorite movie. I’m usually up on such things, so I was taken by surprise at the news that America was rethinking how it watches Gone with the Wind. With so very much on its mind these days, I would have thought rethinking an 80-year old movie would’ve been among the nation’s lowest priorities. And then I saw what the hook was…the deadly pro-Confederate march in Charlottesville last August and the subsequent controversy to remove monuments to the treasonous Confederacy throughout the country (including the baby state of Montana, admitted to the Union almost 40 years after the Civil War but not long enough after it seems not to throw up a monument to Dixie treason). Writer Aisha Harris set off to find out how this classic of American cinema was faring under the klieg lights of historical reexamination, as she put it:

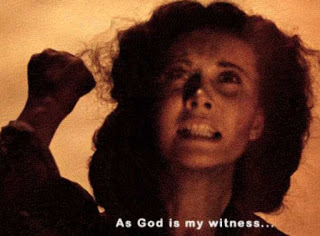

How are cinemas, TV networks, and classrooms rethinking how they present this historical epic and all-time box office king? And could it go the way of Hollywood’s original historical epic and first megablockbuster, 1915’s The Birth of a Nation, leaving it shown very rarely and almost exclusively in academic settings?I feel somewhat an authority on Gone with the Wind. As I mention in I my Goddam Movies post, I worked as an usher in a reserved seat Cinerama theater when Gone with the Wind emerged for its 70mm re-incarnation in 1967. Because it was the 60s and I was a very left leaning college student, I hated the film on first sight for all the right political reasons. But in that job I ended up watching it in whole or in big chunks approximately 125 times. By the end of its near year-long run before my eyes I developed a grudging respect for it. Since the 60s, I’ve watched it at least once a decade without being paid to do so. Despite my appreciation for its aesthetic qualities and storytelling powers, I get all the cultural/political objections to it. They begin with the film’s infamous prolog, which portrays the antebellum South as some kind of American Camelot with references to knights and gallantry and fair maidens. It’s as treacly a description of a slave culture as you’re ever likely to find. To Author Margaret Mitchell’s credit, she does describe that culture as being gone with the wind, so we can’t blame her for the persistence of her fellow Southerners ever since in continuing to push for its restoration.

Between that prolog and Scarlett’s closing observation that “Tomorrow is another day”, there are plenty of other scenes to earn GWTW a spot on The Political Correctness Watch List (or don’t watch, as it were): a union soldier tries to rape Scarlett; a Tara family slave joins the Confederacy to fight against the Union; the rapacious Tara overseer teams up with a black Carpetbagger to exploit the defeated South; and black womanhood is caricatured in the portrayals of Mammy and Prissy.

Those scenes weigh so heavily on the historical sensitivity scale, that they obscure some mitigating elements of the film. First off, as to the attempted rape, the slave enlistment in the Confederate cause, and Carperbagger exploitation, all are historically accurate to the degree that we accept that the rape of women by occupying armies is fairly common in all wars. Second, the two main male characters, Rhett Butler and Ashley Wilkes, both deliver monologs that express fairly deep skepticism about the Southern Cause, so the film is not a full-throated endorsement of the Dixie treason. Third, and most importantly, I think much, if not most, of the lasting popularity of GWTW is due to the charisma of its main character, Scarlett O'Hara. Here’s a passage I just came across, championing the 2017 film Wonder Woman:

Film historians might look back on 2017 and note that this was the year in which certain previously untouchable Hollywood moguls found themselves publicly excoriated, leading to a change in attitudes towards the treatment of women by men in positions of power. What better way to honour that profound societal shift than to celebrate a totem of strong feminity, a superhero who refuses to be kept in the box that society has placed her in; who is comfortable with her own strength but avoids the puffed-up boastfulness of her male counterparts?That description could very well apply to Scarlett O’Hara…surely she was right up there with Hollywood characters of the time portrayed by Katherine Hepburn and Barbara Stanwyck in busting out of society’s box and projecting her own strength. GWTW does far more to advance female empowerment than it does to enshrine slavery and treason. At every turn, Scarlett has to dig down into her own resourcefulness to survive and thrive, and always against the men standing in her way. What drives her, as she famously says, is the will to “never be hungry again”. It should also be noted here, that although Hattie McDaniel expressed regret over her portrayal of Mammy, her character is the only one in the entire film to ever successfully stand up to Scarlett…so the female empowerment was biracial.

The pressing issue these days is whether GWTW should be treated like public displays of Confederate flags, statuary, and sundry memorials. It should not. Those are tax-supported testaments to slavery and treason either directly or in the public lands they occupy. GWTW is both a private enterprise and a creative enterprise. We can pull down Confederate statues in full confidence that no reasonable society should be forced to honor those who conducted a deadly, bloody rebellion against its very being. But a fictional exploration of that rebellion must be granted the creative license and freedom of expression that so many have fought and died for in all our wars.

In her essay, Aisha Harris wonders if perhaps GWTW could experience the same fate as that other controversial film of the Civil War era, Birth of a Nation. That would mean, in her words, “shown very rarely and almost exclusively in academic settings”. One of the most interesting revelations in my long-standing obsession with the city of Pompeii is the way that the Italian government ordered all the many X-rated murals, statuary, jewelry and chotchkes that survived the eruption of Vesusius more than 2000 years ago locked behind closed door in what the Italians call gabinetto segreto, the secret cabinet. Off and on until just about 18 years ago, the secret cabinet was only open to the wealthy and well-connected. It would seem that reserving screenings of GWTW for privileged audiences takes us very close to instituting a gabinetto segreto in our proud open society. I get very anxious when the zeal to stamp out racism amps up, and I can see my beloved Adventures of Huckleberry Finn falling once again in the crosshairs...and that zeal devolves into garden variety book burning.

GWTW, like Huck Finn, should be used as a teaching tool for all. The idea that hiding it away will save us from racism is preposterous. As JD Salinger wrote in The Catcher in the Rye,

I went down by a different staircase, and I saw another “Fuck you” on the wall. I tried to rub it off with my hand again, but this one was scratched on, with a knife or something. It wouldn’t come off. It’s hopeless anyway. If you had a million years to do it, you couldn’t rub off even half the “Fuck you” signs in the world. It’s impossible.

Same goes for racism...which is less an argument for letting it pass than a plea to fight it with education rather than censorship.

Published on October 29, 2017 14:48

No comments have been added yet.