making room

A few weeks ago I phoned my son Jack in Asheville. “How would you feel about me taking over your bedroom at home and turning it into a writing space?” I asked.

I’d hesitated for weeks before raising this idea. But Jack didn’t hesitate in his response. “Oh, that’s fine,” he said, “you can do whatever you want with my room.”

Although we have a tiny office on the first floor of our house, I’ve never written a word in it. The desktop computer is my husband’s and his in-box sits beside it, overflowing with not-urgent papers and clippings and instruction manuals. The window above the desk looks out to the driveway and whatever vehicles happen to be parked there. The counter is a repository for checkbooks and bills to be paid, stamps and envelopes. And the chair, just the right height for Steve, is not very inviting to me. The office is a perfectly good place to write a check or Google driving directions, but it’s not a space my muse has ever chosen to visit.

Most of the words I’ve produced over the last ten years in this house have come from a stool at the kitchen table, where I look out to a view of fields and mountains and sky. I’ve spent countless hours perched there, staring out the windows above the sink while trying to pull my thoughts together. As a mother, as a wife, as a cook and homemaker, and also as a writer, I’ve always been drawn to this room, my own home base, whether I’m chopping something, stirring something, washing something, or writing something. Soups and emails, jars of jam and blog posts, thank you notes and books, all have come from my kitchen. More often than not, several of these things are coming together at once, which means that the written work can easily be shifted to the bottom of my priorities list. No one actually cares if I write or not, but dinner does have to appear on that table every night.

And yet, as summer turned to fall this year, I found myself longing for some other kind of place, a place not in the middle of the action but away from it. A place in which some new work might begin to take shape, privately and quietly. A place where there is nothing that needs to be chopped or watered or cleaned or stirred, where books of memoir and poetry would be easily at hand, and where my laptop and notes and papers don’t have to be put away at the end of the day so that placemats and napkins and silverware can be laid out in their place.

I wasn’t sure, after Magical Journey was published five years ago, whether I would ever write another book. I’m still not sure. But I do know this: turning fifty-nine last week has given me pause. In a year, I’ll be sixty, and there are some things in my life that need to shift, some thinking and writing I very much want to do.

My sixtieth year has begun with an urgent longing for quiet time and open-ended hours and, too, for a space that is devoted not to many things but to one thing: the work of the imagination, the murmurings of the soul, the possibility of articulating and embodying some just-forming ideas about how to live in the world as an older person.

Hence, my call to Jack.

“What about all the things in your desk?” I asked him. “I don’t need any of it,” he said.

That night, I reported our conversation to Steve, and the next morning he summoned me into Jack’s room. “Tell me what you’re envisioning here,” he said, as we looked around at the olive green walls, the bookshelves packed with Stephen King mysteries and old textbooks, the coin jar on the desk, the squash and basketball trophies dimmed by dust.

That night, I reported our conversation to Steve, and the next morning he summoned me into Jack’s room. “Tell me what you’re envisioning here,” he said, as we looked around at the olive green walls, the bookshelves packed with Stephen King mysteries and old textbooks, the coin jar on the desk, the squash and basketball trophies dimmed by dust.

My birthday gift from my husband was carte blanche to create the space I wanted here. And, in truth, my gift from Jack was exactly the same thing. We called a painter.

And then, on the day I began emptying desk drawers and throwing high school notebooks into a trash bag, I snapped a photo of Jack’s collection of Crazybones (a prized first-grade possession) and called him again. “Is there anything here you want me to save or send down to you?” I asked, fighting back sudden, unexpected tears. He asked me to keep his books, to pack them all into boxes till the day when he has a larger place of his own and room for them. The rest could go.

“I’m not attached,” he said simply. “That’s not really my room anymore.”

“I’m not attached,” he said simply. “That’s not really my room anymore.”

What I realized in that moment was that he wasn’t attached, but I was. Taking my son’s bedroom apart and turning it into something else meant I’d no longer peek in on my way past the door and see “him.” Never again would I catch a fleeting sense of his presence there, or see his tiny hippo figurines marching silently across a shelf, or the row of Shel Silverstein books we’d spent so many long-ago hours reading aloud together.

But there’s something else, too. My emotions about dismantling Jack’s bedroom are more complicated than physically acknowledging the end of one chapter and the beginning of another. The truth is, this room was also the setting for some deeply painful struggles, secrets and lies, dashed hopes and heartbreaking realities.

The happy adolescence we hoped our son would enjoy here never happened. More often than not when he was home, the door to this room was closed. What went on behind that door was the beginning of a downward spiral that, at the time, left us all feeling helpless and angry and frightened. After Jack abruptly left home at sixteen for a stint in wilderness therapy and boarding school, it was all I could do to walk past his empty, silent room. It felt like a rebuke. When we sent our son away for treatment, I wasn’t at all sure whether we’d failed him as parents or helped to save him.

The happy adolescence we hoped our son would enjoy here never happened. More often than not when he was home, the door to this room was closed. What went on behind that door was the beginning of a downward spiral that, at the time, left us all feeling helpless and angry and frightened. After Jack abruptly left home at sixteen for a stint in wilderness therapy and boarding school, it was all I could do to walk past his empty, silent room. It felt like a rebuke. When we sent our son away for treatment, I wasn’t at all sure whether we’d failed him as parents or helped to save him.

The other day, I pulled an old, nearly empty Smart Water bottle out of the back of a desk drawer, tossed it into the trash bag, and then, without even thinking, pulled it out again, unscrewed the cap, and tasted the clear liquid. Vodka. Time collapsed and suddenly I was once again the mother of a silent, distant teenager, finding my way in the darkness with nothing to go on but my own maternal intuition. Yes, this excavation is hard. For a lot of reasons.

Jack has been sober for nearly two years. A month shy of twenty-five, he works in a residential treatment center for troubled adolescents, a job he loves and is good at. He shares a comfortable, homey house with two friends and is a devoted “parent” to his beloved dog Carol. His own rocky path into adulthood has given him deep compassion for the kids he works with, and his own commitment to sobriety has taught him a lot about staying with uncomfortable feelings, accepting them, trusting that they, too, will pass.

And so, I shared with Jack that I was having a harder time cleaning out his old room than I’d expected. He got it.

“I just finished writing a new song,” he told me a few minutes later, after I’d composed myself. “It’s about addiction, and denial, and getting sober. I’m pretty excited about it.” I said I’d love to read the lyrics and he promised to send them. Then, after a pause, he said, “Or, I could just rap it for you right now.” And he did.

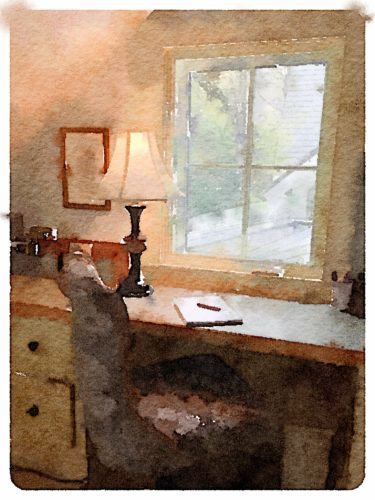

These words are the first to come from my new office on the second floor. The walls are painted a soft shade of blue. There are flowers in a vase, a friend’s drawing on the wall, my own books on the shelves. There’s also a painting Jack did in 8th grade, when he was assigned to copy a work by a master, and some figures he made in grade school that, to me, speak eloquently of the creative, funny, sensitive child he always was and still is at heart. As it turns out, it feels just right to make space here for what has been, for what still is, and for what yet might be.

These words are the first to come from my new office on the second floor. The walls are painted a soft shade of blue. There are flowers in a vase, a friend’s drawing on the wall, my own books on the shelves. There’s also a painting Jack did in 8th grade, when he was assigned to copy a work by a master, and some figures he made in grade school that, to me, speak eloquently of the creative, funny, sensitive child he always was and still is at heart. As it turns out, it feels just right to make space here for what has been, for what still is, and for what yet might be.

In the kitchen below, I can hear the dishwasher completing its cycle. But I’m not tempted to stop what I’m doing in order to put dishes away, or to wipe crumbs off the counter, or to water the fern. There is nothing to pull me away from where I am. When I look up from this screen, I gaze out the window at the stonewall and trees that Jack would have seen as a teenager, had he lifted the shade in his bedroom. One by one, the leaves drift down.

In the kitchen below, I can hear the dishwasher completing its cycle. But I’m not tempted to stop what I’m doing in order to put dishes away, or to wipe crumbs off the counter, or to water the fern. There is nothing to pull me away from where I am. When I look up from this screen, I gaze out the window at the stonewall and trees that Jack would have seen as a teenager, had he lifted the shade in his bedroom. One by one, the leaves drift down.

(My gratitude to Jack — for giving me his old room and, even more, for allowing me to publish this essay. One thing we’ve both learned is that every time we tell of our own struggles, we clear a space for someone else to share theirs, too.)

(My gratitude to Jack — for giving me his old room and, even more, for allowing me to publish this essay. One thing we’ve both learned is that every time we tell of our own struggles, we clear a space for someone else to share theirs, too.)

SaveSave

SaveSave

The post making room appeared first on Katrina Kenison.