A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory

The Mettray reformatory was founded in 1839, some ten kilometres from Tours in the quiet countryside of the Loire Valley. For almost a hundred years the reformatory imprisoned juvenile delinquent boys aged 7 to 21, particularly from Paris. It quickly became a model imitated by dozens of institutions across the Continent, in Britain and beyond. Mettray’s most celebrated inmate, gay thief Jean Genet depicts it in his influential novel Miracle of the Rose [1946] and it is also featured at the climax of philosopher Michel Foucault’s history of modern imprisonment, Discipline and Punish [1975]. The boys worked nine-hour days in the institution’s workshops – making brushes and other basic household implements; they dug its fields and broke stones in its quarries. Such labour was thought conducive to moral reform but it also enabled the institution – which was run by a profit-making private company – to balance its books. In his seventies, Jean Genet suspected that the reformatory was doing rather more than this: making then concealing huge profits from its forced labour. He set about, with a small team of helpers, trying to prove this by plundering the institution’s archives as well as reading widely in the historical sources. The result, The Language of the Wall, was a script for a three-part historical documentary drama for television which retells the story of Mettray from its foundation to its closure as a prison in 1937. Genet could find no hard evidence of profiteering but he dramatizes his own search for it in the script and retells the life of the institution over the hundred years by intertwining often violent incidents from the daily lives of prisoners with scenes from the corridors of power to show how closely the private institution worked alongside the state and how it survived successive changes of regime.

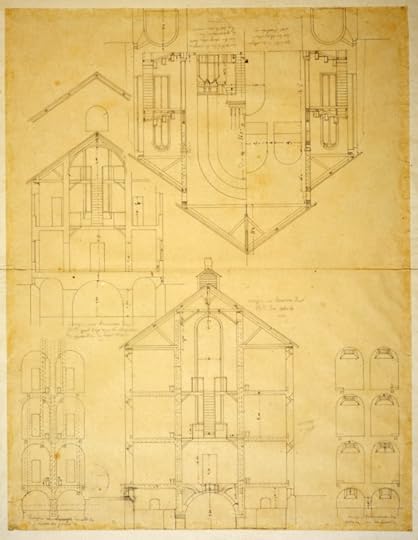

My return to Mettray’s archives in Tours was guided by Genet’s still unpublished script, versions of which are held at the regional archives in Tours and at IMEC. Although Genet rightly ridicules him for his reactionary politics, it is difficult not to admire the technical accomplishment of Mettray’s principal founder, the devout Frédéric-Auguste Demetz. Demetz had been sent to the United States by the French government with prison architect Abel Blouet in 1836 to follow up Alexis de Tocqueville’s earlier visit, the official purpose of which had been to investigate American prisons. Demetz and Blouet were to obtain more precise technical information about them, including detailed drawings.

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173

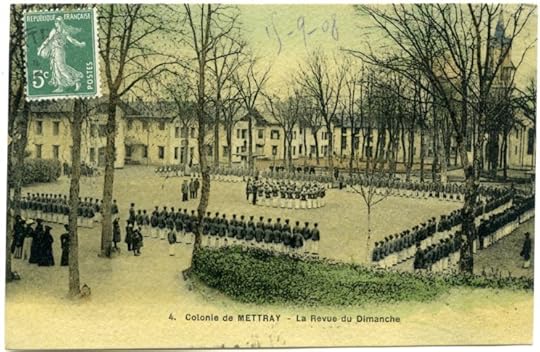

Abel Blouet, Maison Paternelle et Chapelle de la Colonie plan élévation, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J173Blouet subsequently produced drawings for Mettray’s chapel building which show cells in the crypt, as well as in the building behind, a unit which the institution ran as a money-making enterprise by encouraging middle-class families to send wayward sons for a short spell of “paternal correction,” during which they experienced individual tuition and could also hear Mass in the adjacent chapel from the privacy of their cells without having to mix with the working-class delinquents in the chapel. Demetz was a brilliant publicist for his institution, marketing it and carefully managing its visibility to the outside world. He boasted that Mettray was “sans grilles ni murailles” (without bars or walls) and in one sense this was true: there was no perimeter wall, yet in addition to the punishment cells concealed in the chapel and elsewhere there were frequent roll-calls and escapees were rounded up by the local peasantry, alerted by the ringing of the chapel bell, and incentivized by the payment of a reward. Sometimes they killed escapees. Demetz welcomed philanthropic tourists but only on Sundays, when they witnessed the institution’s weekly military parade, La Revue du Dimanche.

Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J344.

Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire, 114J344.The institution provided a hotel and even postcards for visitors to spread the news of its success in taking wayward criminal children and remoulding them into disciplined servants of the established order: inmates could leave Mettray a few years early if they joined the armed forces so many did, becoming troops in the colonial armies. Genet’s script is accurate in showing the presence of soldiers from Mettray at key moments in the colonisation of Algeria, as well as in Mexico and Indochina. Demetz was an expert carceral entrepreneur who not only governed the prison but also the surrounding local population, enlisting them as – in effect – auxiliary prison guards to substitute for the absent perimenter wall. In Paris he garnered financial support from the governing classes in a similar way. By capitalising on the fear of crime to further his own institutional agenda, Demetz’s approach points forward to the ubiquitous work of today’s “(in)security professionals,” to use Didier Bigo’s suggestive formulation.

Featured image credit: Colonie de Mettray – La Revue du Dimanche, courtesy of Les Archives Départementales d’Indre-et-Loire

The post A prison without walls? The Mettray reformatory appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers