CARPE NOCTEM INTERVIEW: LoIS ROMA-DEELEY

Franciscan University Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

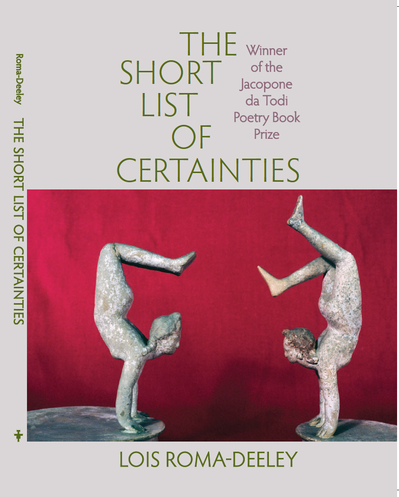

Franciscan University Press, 2017 THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I was most fortunate to work with Franciscan University Press as they actively sought my input into the whole production of the book.

I begin my book with two quotes that set the tone and structure::

Hope has two beautiful daughters. Their names are anger and courage; anger at the way things are, and courage to see that they do not remain the way they are. —St. Augustine of Hippo

You must wager. It is not optional. You are embarked. —Blaise Pascal

I came upon this image of 3rd century Greek acrobats, which conveyed the two daughters as well as a sense of the journey.

The acrobats are balancing on their hands. These figures represent the twin daughters of Hope —Anger and Courage. And it is these personas who create a narrative arc in the book. They materialize and dematerialize throughout time, physical space, and social boundaries to liberate the world while destroying classic mandates. The cover’s red background represents passion. The twins struggle within themselves, argue with each other, and rage at the world as they fight against work-a-day violence, social injustices, and even Hope itself.

The signature poem of this book, The Short List of Certainties, was the first poem I wrote for this book and is the last poem in the collection. It is a kind of coda to the entire collection. And that is, we are flawed human beings who struggle and there is something noble and praiseworthy in the fact that we choose to struggle and not give up.

The key words to this book are journey, anger, courage. The book is structured as journey away from our deepest feelings of anger and despair, and toward a place of hope and courage. At each and every turn, there is a choice to be made and no easy answers to be found for the brokenness in ourselves and in the world.

What were you trying to achieve with your chapbook/book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create? Who lives in it?

“There’s a price we pay,” as the poet Deborah Keenan says of this book, “for being alive.”

I wanted to explore the many ways in which we are blind. Blind to our deepest feelings of anger, hope, despair and courage. Blind to the depths of our fears and the heights of our noblest selves. Blind to our choices. Blind to the fact that we do have choices. Blind to the numbing effects of work-a-day violence. Blind to the cascading effects of social injustice in our personal lives as well as our communal ones.

All the voices in The Short List of Certainties are as ethereal as Hope, Anger, Courage and the poetic narrator. And the voices are as earth-bound as a boy trying to save his sister from sexual abuse, young girls in walking home from school, a refugee in a creative writing class, co-workers at a dead-end job, hikers in the back country of Arizona, a woman who compulsively cleans her neighborhood, lovers lying in each other’s arms—just to name just a few personas who populate this book.

We encounter them in a specific spiritual, psychological and/or physical state. They are caught in the moment before--or the moment just after--recognizing something essential in themselves, their lives, their society. All endeavor to balance on the sum total of their beliefs and actions.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

I write very slowly. And I revise even more slowly.

Before I begin a big project, I read a lot of poetry, and, when appropriate, I do a lot of research. I love reading literary criticism and find that it, ultimately, frees me to approach poetry in different ways.

Often, I find that drafts of poems will address a question I didn’t know I had asked. My revision process is to “dig deeper” until the question embedded in the poem presents itself to me clearly and coherently.

My favorite revision strategy is create multiple drafts. I often experiment with “messiness.” For example, I like to take a poem apart, line by line, and see what it might be telling me or asking me. Sometimes I might overwrite a section on, let’s say, termites. I’ll put into the draft every detail I know about termites. How they fly. Where they live. Why they construct gardens inside huge mud walls. Then I might pare those pages down to just two stanzas. Or I might play with verb tenses just to see what it might produce. Or switch pronouns. Or eliminate pronouns. I might put the whole poem into a prose form. Or pound the each line into formal structure like a sonnet or villanelle.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

I lay the pages out and see which poems speak to each other. I look for a thread that I can draw through the entire book. Once I find that, the ordering becomes natural and inevitable.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

A great poem lives inside me. I return to it again and again as it gives me something essential every time. Sometimes it is cadence. Sometimes it is the sound of one word or line. Sometimes it is meaning. But I am always surprised by how a great poem reaches inside me and moves me elsewhere. A great poem surprises me, thrills me, comforts me…every time, all the time.

What’s one of the more crucial poems in the book for you? (Or what’s your favorite poem?) Why? How did the poem come to be? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book, or somewhere else in the process?

A crucial poem in this collection is “Two Daughters” because, after writing it, it clarified for me the entire narrative arc of the book. I wrote it about a fourth of the way into the manuscript. This poem articulated for me the voices of the daughters of Hope…Anger and Courage.

Two Daughters

Like a divining rod, my pick-up pulls me toward you--

taking the back road, winding around mountains,

down to the valley, past where the sheep bridge once stood,

high above the old mining camp and pine tree forest.

Then, the truck stalls.

Near pallets of abandoned brick and stone dry wells,

I kick the dust with the tip of my boot

just to see the birds scatter

and fly through broken windows of empty houses.

Standing in the street, I’m waving my arms in circles,

shouting, good and loud, as if my need alone is enough

to make ghosts leave

the peace of their graves. Finally, I find you

sitting in a patch of brown grass in front of a stranger’s home,

hypnotized by the wind groaning through the wood walls,

and moss growing up the porch stairs. Your lips move

but nothing gets said. There’s a tapping at the top of the tin roof--

something kind and beautiful has come for us.

But I won’t look.

Lighting yet one more cigarette, a smoke ring drifts out my mouth,

disappears in the air. Remembering now

all the times I refused to eat,

enjoying the dizziness of my own hunger--

how emptiness is

the white room with no doors, no window, no sound

and me, shoulders pressed against the back wall,

with fists upright and ready to fight.

As evening approaches, fireflies burst into luminescence.

Miles and miles away, a train whistle blows twice.

I inhale, deeply. My cigarette glows red.

A hummingbird flies nervously above your head.

I turn my face to the west and wait--

the sky, now a holocaust of light, calls out:

burn a path through this world

or move on to the next.

Tell us something about the most difficult thing you encountered in this book’s journey. And/or the most wonderful?

Time to focus exclusively on the poems as they are emerging in a manuscript is always difficult. Life is happening all around me and I want to pay attention, to be present. However, I have been granted Fellowship Residencies by the Ragdale Foundation on several occasions. This past residency enabled me to complete most of this manuscript. My retreat was absolutely wonderful!

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

First, I’d ask her or him if the present condition in our culture confuses and angers her or him as much as it does me. Then I’d say, “Here, take a look at these. You’re not alone.”

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

For me, poetry crystallizes the unseen. What scares me the most about being a writer is not writing. I love the moment in my writing when the poem tells me “I’m done.”

I’ve heard poets say they’re writing the same story over and over in their poems. Is that true for you? If not, what obsessions or concerns reoccur in your work?

I have two threads I pursue all the time: the “the line in between” and the nobility of the human struggle.

Do you think poets have a responsibility as artists to respond to what’s happening in the world, and put that message out there? Does your work address social issues?

The great poet Muriel Rukeyser said, “The universe is made of stories, not of atoms.” I believe it is also true that the universe turns on the need to bear witness to those stories and it is the writer’s duty to do so. Whether it be the petroglyphs of the Deer Valley Preserve in Phoenix, Arizona or the 1,000-year-old Book of Kells in Dublin, there is an insistent human urge to be heard and to be remembered—with dignity and respect.

After 9/11 happened my students were despondent, to say the least. They came into class that day and said to me, “What's the use of writing anything when people are jumping out of buildings?”

I responded by saying: “We need writers now more than ever. We need our writers to try and make sense of all this. To give us context. To try and make some meaning out of chaos and cruelty. To give us something to hold onto.”

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I have entire shelves full of reference material. Just to name a few as examples: Dictionary of Scientific Literacy; The New York Public Library Desk Reference; Dictionary of Word Origins; The Dictionary of Clichés; A Dictionary of Symbols; Poetry Dictionary; The Book of Forms; Encyclopedia of Feminism; WomanWords; Critical Theory Since Plato; Critical Theory Since 1965; Sacred Symbols; The Politics of Women’s Bodies; Space-Time and Beyond; Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage; The Bible; Partridge’s Concise Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English; The Mirror and the Lamp; Signs of the Times; Modern Literary Criticism; New York Times Book of Gardens; Stealing the Language.

I also have multiple thesauri, literary biographies, a four-drawer file cabinet of annotated articles and many, many books by contemporary poets as well as various poetry journals.

What are you working on now?

Two manuscripts have presented themselves to me. One is in the universal voice of Body and all the poems in this collection will have no gender pronouns. Body will speak from and about various physical experiences. It might be called “Body, This.” The other manuscript is tentatively titled “Sleep Walking Through the City.” These poems explore various aspects of marginality as well as the willingness—or refusal—to change.

Favorite places and times of day or night to work?

I work in the very early morning when it’s still quite dark out and when the world is breathing slowly and deeply.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

I buy lots of poetry books and a fair number of journals. What’s on my bookshelf now are: Heather McHugh, Upgraded to Serious; Maggie Smith, The Well Speaks of Its Own Poison; Natalie Diaz, When My Brother Was an Aztec; Patricia Colleen Murphy, Hemming Flames; and Czeslaw Mislosz, The Poetry of Witness.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Denise Levertov, Jane Hirshfield, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, Maggie Anderson, Robert Creeley.

***

Purchase The Short List of Certainties.

Lois Roma-Deeley’s most recent full-length book of poetry is The Short List of Certainties, winner of the Jacopone da Todi Book Prize (Franciscan University Press, 2017). She is the author of three previous collections of poetry: Rules of Hunger, northSight and High Notes—a Paterson Poetry Prize Finalist. Roma-Deeley’s poems have been featured in numerous literary journals and anthologies, nationally and internationally. She’s served as a creative writing contest judge at the local, state and national levels. Roma-Deeley is Associate Editor of Presence. She was named U.S. Professor of the Year, Community College, by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and CASE, 2012-2013. Roma-Deeley is the recipient of a 2016 Arizona Commission on the Arts Grant. Visit her at www.loisroma-deeley.com. Read her blog at http://ciaopoetry.blogspot.com.

Lois Roma-Deeley’s most recent full-length book of poetry is The Short List of Certainties, winner of the Jacopone da Todi Book Prize (Franciscan University Press, 2017). She is the author of three previous collections of poetry: Rules of Hunger, northSight and High Notes—a Paterson Poetry Prize Finalist. Roma-Deeley’s poems have been featured in numerous literary journals and anthologies, nationally and internationally. She’s served as a creative writing contest judge at the local, state and national levels. Roma-Deeley is Associate Editor of Presence. She was named U.S. Professor of the Year, Community College, by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and CASE, 2012-2013. Roma-Deeley is the recipient of a 2016 Arizona Commission on the Arts Grant. Visit her at www.loisroma-deeley.com. Read her blog at http://ciaopoetry.blogspot.com.Connect with Lois Roma-Deeley on social media using the icons below. #element-29dbf136-7f3c-4c1b-b1d8-81e8486ba776 .wgtc-widget-frame { width: 100%;}#element-29dbf136-7f3c-4c1b-b1d8-81e8486ba776 .wgtc-widget-frame iframe { width: 100%; height: 100%; border-collapse: collapse; border: 0 none;}

Published on September 29, 2017 03:57

No comments have been added yet.