A more natural Disjunction Elimination rule?

We work in a natural deduction setting, and choose a Gentzen-style layout rather than a Fitch-style presentation (this choice is quite irrelevant to the point at issue).

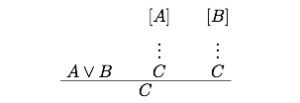

The standard Gentzen-style disjunction elimination rule encodes the uncontroversially valid mode of reasoning, argument-by-cases: Now, with this rule in play, how do we show

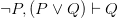

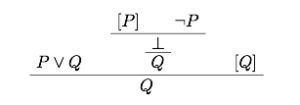

Now, with this rule in play, how do we show  ? Here’s the familiar line of proof:

? Here’s the familiar line of proof: But familiarity shouldn’t blind us to the fact that there is something really rather odd about this proof, invoking as it does the explosion rule, ex falso quodlibet. After all, as it has been well put:

But familiarity shouldn’t blind us to the fact that there is something really rather odd about this proof, invoking as it does the explosion rule, ex falso quodlibet. After all, as it has been well put:

Suppose one is told that A

B holds, along with certain other assumptions X, and one is required to prove that C follows from the combined assumptions X, A

B. If one assumes A and discovers that it is inconsistent with X, one simply stops one’s investigation of that case, and turns to the case B. If C follows in the latter case, one concludes C as required. One does not go back to the conclusion of absurdity in the first case, and artificially dress it up with an application of the absurdity rule so as to make it also “yield” the conclusion C.

Surely that is an accurate account of how we ordinarily make deductions! In common-or-garden reasoning, drawing a conclusion from a disjunction by ruling out one disjunct surely doesn’t depend on jiggery-pokery with explosion. (Of course, things will be look even odder if we don’t have explosion as a primitive rule but treat instances as having to be derived from other rules.)

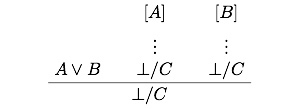

Hence there seems to be much to be said — if we want our natural deduction system to encode very natural basic modes of reasoning! — for revising the disjunctive elimination rule to allow us to, so to speak, simply eliminate a disjunct that leads to absurdity. So we want to say, in summary, that if both limbs of a disjunction lead to absurdity, then ouch, we are committed to absurdity; if one limb leads to absurdity and the other to C, we can immediately, without further trickery, infer C; if both limbs lead to C, then again we can derive C. So officially the rule becomes where if both the subproofs end in

where if both the subproofs end in  so does the whole proof, but if at least one subproof ends in C, then the whole proof ends in C. On a moment’s reflection isn’t this, pace the tradition, the natural rule to pair with the disjunction introduction rules? (At or at least natural modulo worries about how to construe “

so does the whole proof, but if at least one subproof ends in C, then the whole proof ends in C. On a moment’s reflection isn’t this, pace the tradition, the natural rule to pair with the disjunction introduction rules? (At or at least natural modulo worries about how to construe “ ” — I think there is much to be said for taking this as an absurdity marker, on a par with the marker we use to close of branches containing contradictions on truth trees, rather than a wff that can be embedded in other wffs.)

” — I think there is much to be said for taking this as an absurdity marker, on a par with the marker we use to close of branches containing contradictions on truth trees, rather than a wff that can be embedded in other wffs.)

If might be objected that this rule offends against some principle of purity to the effect that the basic, really basic, rules for another connective like disjunction should not involve (more or less directly) another connective, negation. But it is unclear what force this principle has, and in particular what force it should have in the selection of rules in an introductory treatment of natural deduction.

The revised disjunction rule isn’t a new proposal! — it has been on the market a long time. In the next post, credit will be given where credit is due. But for now I want the consider the proposal as a stand-alone recommendation, not as part of any larger revisionary project. The revised rule is obviously well-motivated, makes elementary proofs shorter and more natural. What’s not to like?