Introducing Bobbi Miller

I’m so excited to be joining the Smack Dab in the Middle! With a background in American folklore, I write historical fiction middle grade, focusing on forgotten characters (usually girls, who are not represented enough) and events (because I think as a nation, we are historically illiterate and have forgotten our own story) that helped build the American landscape. I like the challenge of writing historical fiction.

History is literature, David McCullough says. The artistic nature of historical fiction presents several challenges, especially in books for children. Events must be “winnowed and sifted”, as Sheila Egoff explains, in order to create forward movement that leads to a resolution. Authors choose between which details to include, and exclude, and this choice is wholly dependent upon the character’s goal. More important, resolution rarely happens in history. The same with happy endings. Because of the culling process, critics often claim that historical fiction is inherently biased.

Yet, nothing about history is obvious, and facts are often open to interpretation. In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, but he didn’t discover America. In fact (all puns intended), some would say he was less an explorer and more of a conqueror. History tends to be written by those who survived it. No history is without its bias. The meaning of history, just as it is for the novel, lays “not in the chain of events themselves, but on the historian’s [and writer’s] interpretation of it,” as Jill Paton Walsh once noted.

One hundred fifty one years ago, twelve thousand Confederate forces gathered along Seminary Ridge. Almost a mile away, at the end of an open field, a copse of trees marked the Union line standing firm on Cemetery Ridge. When the signal was given, the men marched across the field. The line had advanced less than two hundred yards when the federals sent shell after shell howling into their midst. Boom! Men fell legless, headless, armless, black with burns and red with blood. Still they marched on across that field.

As I was researching another book, I came across a small newspaper article dated from 1863. It told of a Union soldier on burial duty, following this Battle at Gettysburg, coming upon a shocking find: the body of a female Confederate soldier. It was shocking because she was disguised as a boy. At the time, everyone believed that girls were not strong enough to do any soldiering; they were too weak, too pure, too pious to be around roughhousing boys. It was against the law for girls to enlist. This girl carried no papers, so he could not identify her. She was buried in an unmarked grave. A Union general noted her presence at the bottom of his report, stating “one female (private) in rebel uniform.” The note became her epitaph. I decided I was going to write her story.

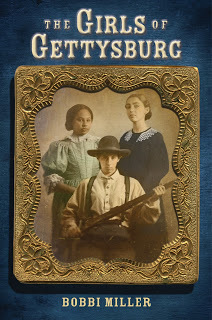

Some facts, such as dates of specific events, are fixed. We know, for example, that the Battle of Gettysburg occurred July 1 to July 3, in 1863. The interpretations of what happened over those three days remains a favorite in historical fiction. My interpretation of the battle, in Girls of Gettysburg (Holiday House, August 2014), featured three perspectives that are rare in these historical fiction depictions: the daughter of a free black living seven miles north from the Mason-Dixon line, the daughter of the well-to-do local merchant, and a girl disguised as a Confederate soldier. The plot weaves together the fates of these girls, a tapestry that reflects their humanity, heartache and heroism in a battle that ultimately defined a nation.

The literary process that defines historical fiction allows readers to connect emotionally to historical figures and events. It introduces readers to different points of view. As Tarry Lindquist (1995) said, historical fiction “puts people back into history.” While textbooks tend to underscore coverage, this lacks depth, and as a result, “individuals—no matter how famous or important—are reduced to a few sentences…Good historical fiction presents individuals as they are, neither good nor bad.”

Historical fiction helps young readers develop a feeling for a living past, illustrating the continuity of life, according to Karen Cushman. Historical fiction, “like all good history, demonstrates how history is made up of the decisions and actions of individuals and that the future will be made up of our decisions and actions.”

Historical fiction makes the facts matter to the reader. If I didn’t get the facts right, creating characters true to their time and place, the readers won’t care about the facts. For me, the only way to discover this emotional truth was to walk the battlefield of Gettysburg, and witness that landscape where my characters lived over one hundred and fifty years ago. Besides extensive reading, including scholarly pieces, diaries and journals , eyewitness accounts, military reports, I traveled to Gettysburg four times, walking the battlefield and talking to re-enactors and the park rangers.

History is story. And our history is full of amazing stories. That’s why I write historical fiction.

What's your favorite historical fiction?

Thank you for stopping by!

Bobbi Miller

Published on September 15, 2017 04:28

No comments have been added yet.