Bad at 30: Inside the album sessions and Michael Jackson's split with Quincy Jones

Written by Mike Smallcombe the author of Making Michael, a book on the career of Michael Jackson. Find out more here.In the summer of 1985, Michael began working on demos and ideas in earnest for his next album, which became Bad. He was joined at his Hayvenhurst home studio by the four-man crew of Matt Forger, Bill Bottrell, John Barnes and Christopher Currell, who became known as the ‘B-Team’. Together they worked without the influence of the ‘A-Team’, people such as producer Quincy Jones, engineer Bruce Swedien and songwriter Rod Temperton. Over the course of the second half of 1985 and most of 1986, Michael and the B-Team created many demos that would later be brought to Quincy’s attention at the main Westlake studio sessions, including 'Bad', 'The Way You Make Me Feel', 'Dirty Diana' and 'Smooth Criminal'. Although Michael began the project without Quincy, the plan was to team up with him at Westlake at a later stage for the main production. Michael was simply at the stage of his creative life where he was ready to write most of the tracks for his next album himself, and experimenting and recording away from Westlake and Quincy would enable him to have more of a say in the overall production. Read a chapter: The making of Michael Jackson's Dangerous album“Michael was beginning to develop a real creative growth and gaining skills, not only in writing, but also in the production area and just taking more control over his music,” Forger explained. “It was something Quincy actually encouraged, he felt Michael should make his next album more his own.” Bottrell described it like ‘a teenager leaving the nest’. “Michael was growing and wanted to experiment free of the restrictions of the Westlake scene,” he said. “This is how he started to express his creative independence.”In August 1986, after more than two years of on-off work, Michael was ready to join forces with the A-Team again, as he felt he had enough material to present to Quincy. It was essentially the A-Team taking over from the B-Team, although Michael would continue to work at his home studio.

Written by Mike Smallcombe the author of Making Michael, a book on the career of Michael Jackson. Find out more here.In the summer of 1985, Michael began working on demos and ideas in earnest for his next album, which became Bad. He was joined at his Hayvenhurst home studio by the four-man crew of Matt Forger, Bill Bottrell, John Barnes and Christopher Currell, who became known as the ‘B-Team’. Together they worked without the influence of the ‘A-Team’, people such as producer Quincy Jones, engineer Bruce Swedien and songwriter Rod Temperton. Over the course of the second half of 1985 and most of 1986, Michael and the B-Team created many demos that would later be brought to Quincy’s attention at the main Westlake studio sessions, including 'Bad', 'The Way You Make Me Feel', 'Dirty Diana' and 'Smooth Criminal'. Although Michael began the project without Quincy, the plan was to team up with him at Westlake at a later stage for the main production. Michael was simply at the stage of his creative life where he was ready to write most of the tracks for his next album himself, and experimenting and recording away from Westlake and Quincy would enable him to have more of a say in the overall production. Read a chapter: The making of Michael Jackson's Dangerous album“Michael was beginning to develop a real creative growth and gaining skills, not only in writing, but also in the production area and just taking more control over his music,” Forger explained. “It was something Quincy actually encouraged, he felt Michael should make his next album more his own.” Bottrell described it like ‘a teenager leaving the nest’. “Michael was growing and wanted to experiment free of the restrictions of the Westlake scene,” he said. “This is how he started to express his creative independence.”In August 1986, after more than two years of on-off work, Michael was ready to join forces with the A-Team again, as he felt he had enough material to present to Quincy. It was essentially the A-Team taking over from the B-Team, although Michael would continue to work at his home studio.  Michael during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987The day before work began Michael had his huge Synclavier system, which was used to record the demos at Hayvenhurst, transported to Westlake. The state-of-the-art digital synthesiser, sampler and workstation could imitate most instruments and would change the way Michael’s music was recorded. The Synclavier was new to Quincy, who planned to re-record the demo tracks with his A-Team session musicians. But Michael said he preferred the Synclavier versions. “This happened all the time, so soon, Quincy changed his way of working and we began to use the Synclavier for everything,” Chris Currell said.But by early 1987, Michael was still concerned that the tracks were not sounding the same as when they were originally recorded into the Synclavier at Hayvenhurst. “He had discussed this with Bruce [Swedien], but he did not seem to understand Michael’s concern,” Christopher Currell said.

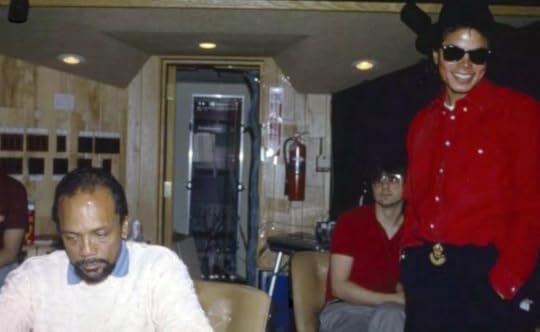

Michael during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987The day before work began Michael had his huge Synclavier system, which was used to record the demos at Hayvenhurst, transported to Westlake. The state-of-the-art digital synthesiser, sampler and workstation could imitate most instruments and would change the way Michael’s music was recorded. The Synclavier was new to Quincy, who planned to re-record the demo tracks with his A-Team session musicians. But Michael said he preferred the Synclavier versions. “This happened all the time, so soon, Quincy changed his way of working and we began to use the Synclavier for everything,” Chris Currell said.But by early 1987, Michael was still concerned that the tracks were not sounding the same as when they were originally recorded into the Synclavier at Hayvenhurst. “He had discussed this with Bruce [Swedien], but he did not seem to understand Michael’s concern,” Christopher Currell said.  Michael, Quincy and Chris Currell (behind) during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987“Michael was concerned that the punch of the music was being lost somehow. Michael called a meeting with me and his manager, Frank DiLeo, to listen to the original tracks at Michael’s studio on the Synclavier. Frank agreed that there was a difference. Michael especially noticed this on the song ‘Smooth Criminal’.”Although Michael and Quincy were producing the album together, they had conflicting ideas about the sounds. Michael was so unhappy with what was happening at Westlake that he even dared to make his own changes behind Quincy’s back.“Something major happened during these sessions,” one musician said. “When you wanted someone to work on a song for you away from the studio, you would make them ‘slave tapes’, and one day Michael took home slave tapes to work on at Hayvenhurst, away from Westlake and away from Quincy. Quincy couldn’t believe it. No one took tapes away from a Quincy Jones production and made changes behind his back!”

Michael, Quincy and Chris Currell (behind) during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987“Michael was concerned that the punch of the music was being lost somehow. Michael called a meeting with me and his manager, Frank DiLeo, to listen to the original tracks at Michael’s studio on the Synclavier. Frank agreed that there was a difference. Michael especially noticed this on the song ‘Smooth Criminal’.”Although Michael and Quincy were producing the album together, they had conflicting ideas about the sounds. Michael was so unhappy with what was happening at Westlake that he even dared to make his own changes behind Quincy’s back.“Something major happened during these sessions,” one musician said. “When you wanted someone to work on a song for you away from the studio, you would make them ‘slave tapes’, and one day Michael took home slave tapes to work on at Hayvenhurst, away from Westlake and away from Quincy. Quincy couldn’t believe it. No one took tapes away from a Quincy Jones production and made changes behind his back!” Michael and Quincy with engineer Bruce Swedien during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987With Michael wanting more of a say in the production of the album, there was inevitable friction between him and Quincy. “There was definite friction there,” musician Larry Williams said. “Michael was very eager to prove he could produce, as well as sing and dance.”Michael Boddicker shares this view. “Michael and Quincy began bumping heads a little on this album,” he said. “Quincy had his way and Michael had his way. Michael wanted a big say on production and things were starting to get a little fractured. Michael felt that Quincy had made him the star, and realised he needed to write and produce more. But with two producers on an album, problems are going to arise.”Michael admitted there was tension, especially when it came to sound. “We fight,” he said. “We disagreed on some things. If we struggle at all, it’s about new stuff, the latest technology. I’ll say, ‘Quincy, you know, music changes all the time’. I want the latest drums sounds that people are doing. I want to go beyond the latest things.”

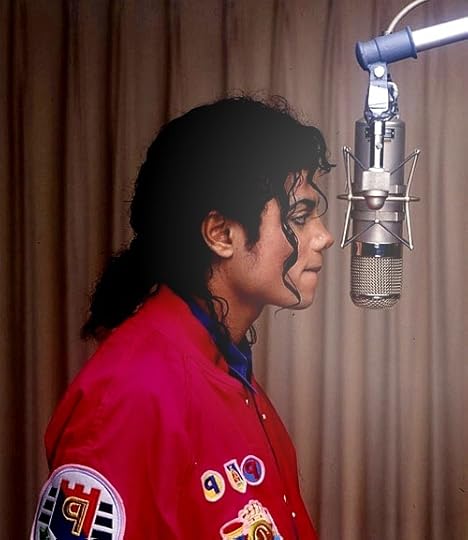

Michael and Quincy with engineer Bruce Swedien during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987With Michael wanting more of a say in the production of the album, there was inevitable friction between him and Quincy. “There was definite friction there,” musician Larry Williams said. “Michael was very eager to prove he could produce, as well as sing and dance.”Michael Boddicker shares this view. “Michael and Quincy began bumping heads a little on this album,” he said. “Quincy had his way and Michael had his way. Michael wanted a big say on production and things were starting to get a little fractured. Michael felt that Quincy had made him the star, and realised he needed to write and produce more. But with two producers on an album, problems are going to arise.”Michael admitted there was tension, especially when it came to sound. “We fight,” he said. “We disagreed on some things. If we struggle at all, it’s about new stuff, the latest technology. I’ll say, ‘Quincy, you know, music changes all the time’. I want the latest drums sounds that people are doing. I want to go beyond the latest things.”  Michael recording 'I Just Can't Stop Loving You' during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987Quincy was also trying to push Michael in the direction of rap, so he set up a meeting between Michael and hip-hop group Run DMC, who were at the height of their popularity. They were supposed to collaborate on an antidrug track, ‘Crack Kills’, but the plan fell through.Some members of the A-Team became so disconcerted about Michael’s idea of also recording the album after hours with the B-Team at Hayvenhurst, that they demanded the likes of Bill Bottrell and John Barnes stop working on it. Barnes left the project, while Bottrell was fired by Frank DiLeo with the promise that he would be re-hired for the next album, which became Dangerous. For this project, Michael made the decision to dispense with the services of Quincy, even though the three albums the pair recorded together had sold over 70 million copies in a decade. One of the reasons Michael no longer wanted to work with Quincy was because he felt the producer was taking too much credit for his work. Record label chief Walter Yetnikoff recalls Michael telling him he didn’t want Quincy to win any awards at the Grammys in 1984 for his role in producing Thriller. “People will think he’s the one who did it, not me,” Michael told Yetnikoff. Quincy believes that key members of Michael’s entourage were whispering in his ear telling him that he had been getting too much credit.

Michael recording 'I Just Can't Stop Loving You' during the Bad sessions at Westlake Studio, 1987Quincy was also trying to push Michael in the direction of rap, so he set up a meeting between Michael and hip-hop group Run DMC, who were at the height of their popularity. They were supposed to collaborate on an antidrug track, ‘Crack Kills’, but the plan fell through.Some members of the A-Team became so disconcerted about Michael’s idea of also recording the album after hours with the B-Team at Hayvenhurst, that they demanded the likes of Bill Bottrell and John Barnes stop working on it. Barnes left the project, while Bottrell was fired by Frank DiLeo with the promise that he would be re-hired for the next album, which became Dangerous. For this project, Michael made the decision to dispense with the services of Quincy, even though the three albums the pair recorded together had sold over 70 million copies in a decade. One of the reasons Michael no longer wanted to work with Quincy was because he felt the producer was taking too much credit for his work. Record label chief Walter Yetnikoff recalls Michael telling him he didn’t want Quincy to win any awards at the Grammys in 1984 for his role in producing Thriller. “People will think he’s the one who did it, not me,” Michael told Yetnikoff. Quincy believes that key members of Michael’s entourage were whispering in his ear telling him that he had been getting too much credit. Quincy also felt Michael had lost faith in him and his knowledge of the market. “I remember when we were doing Bad I had [Run] DMC in the studio because I could see what was coming with hip-hop,” he said. “And [Michael] was telling Frank DiLeo, ‘I think Quincy’s losing it and doesn’t understand the market anymore. He doesn’t know that rap is dead’.” Michael was also said to be unhappy after Quincy gave him a tough time over the inclusion of ‘Smooth Criminal’ on Bad.Most significantly, Michael wanted complete production freedom for his next project. On Bad Michael wasn’t always able to produce the way he wanted to, especially when it came to working with the Synclavier, because co-producer Quincy had his own methods. Future producer Brad Buxer said Michael wasn’t angry with his one-time mentor. “He has always had an admiration for him and an immense respect,” Buxer said. “But Michael wanted to control the creative process from A to Z. Simply put, he wanted to be his own boss. Michael was always very independent, and he also wanted to show that his success was not because of one man, namely Quincy.”The content in this article is from the chapter on Bad in Making Michael, a book on the career of Michael Jackson by Mike Smallcombe. Find out more here.

Quincy also felt Michael had lost faith in him and his knowledge of the market. “I remember when we were doing Bad I had [Run] DMC in the studio because I could see what was coming with hip-hop,” he said. “And [Michael] was telling Frank DiLeo, ‘I think Quincy’s losing it and doesn’t understand the market anymore. He doesn’t know that rap is dead’.” Michael was also said to be unhappy after Quincy gave him a tough time over the inclusion of ‘Smooth Criminal’ on Bad.Most significantly, Michael wanted complete production freedom for his next project. On Bad Michael wasn’t always able to produce the way he wanted to, especially when it came to working with the Synclavier, because co-producer Quincy had his own methods. Future producer Brad Buxer said Michael wasn’t angry with his one-time mentor. “He has always had an admiration for him and an immense respect,” Buxer said. “But Michael wanted to control the creative process from A to Z. Simply put, he wanted to be his own boss. Michael was always very independent, and he also wanted to show that his success was not because of one man, namely Quincy.”The content in this article is from the chapter on Bad in Making Michael, a book on the career of Michael Jackson by Mike Smallcombe. Find out more here.

Published on August 31, 2017 05:52

No comments have been added yet.