Mistrust, Efficacy and the New Civics – a whitepaper for the Knight Foundation

When things get serious in the media space, my friends at the Knight Foundation rally the troops. Last week, I was invited to a workshop Knight held with the Aspen Institute on trust, media and democracy in America. I prepared a whitepaper for the workshop, which I’m publishing here at the suggestion of several of the workshop participants, who found it useful.

The paper I wrote – “Mistrust, efficacy and the new civics: understanding the deep roots of the crisis of faith in journalism” – served two purposes for me. First, it’s a rough outline of the book I’m working on this next year about mistrust and civics, which means I can pretend that I’ve been working on my book this summer. Second, it let me put certain stakes in the ground for my discussion with my friends at Knight. Conversations about mistrust in journalism have a tendency to focus on the uniqueness of the profession and its critical civic role in the US and in other open societies. I wanted to be clear that I think journalism has a great deal in common with other large institutions that are suffering declines in trust. Yes, the press has come under special scrutiny due to President Trump’s decision to demonize and threaten journalists, but I think mistrust in civic institutions is much broader than mistrust in the press.

Because mistrust is broad-based, press-centric solutions to mistrust are likely to fail. This is a broad civic problem, not a problem of fake news, of fact checking or of listening more to our readers. The shape of civics is changing, and while many citizens have lost confidence in existing institutions, others are finding new ways to participate. The path forward for news media is to help readers be effective civic actors. If news organizations can help make citizens feel powerful, like they can make effective civic change, they’ll develop a strength and loyalty they’ve not felt in years.

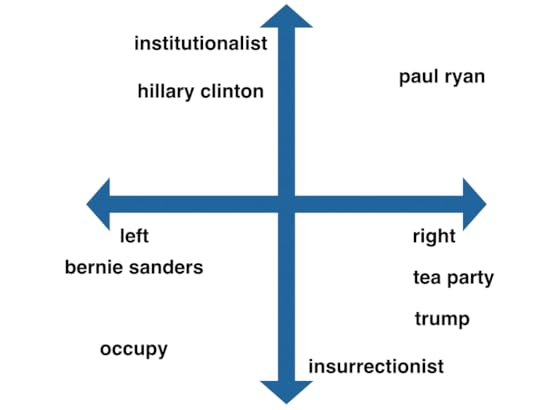

To my surprise and delight, the workshop participants needed little or no convincing that journalism’s problems were part of a larger anti-institutional moment in America. I brought in Chris Hayes’s idea that “left/right” is no longer as useful a distinction in American politics as “insurrectionist/institutionalist”, and we had a helpful debate about what it would mean to bring insurrectionists – those who believe our institutions are failing and need to be replaced by newer structures – into a room full of institutionalists – people who see our institutions are central to our open society, in need of strengthening and reinforcement, but worth defending and preserving.

What started to emerge was a two-dimensional grid of left/right and insurrectionist/institutionalist to understand a picture of American politics that can include both the Occupy Movement and Hillary Clinton as leftists, and Donald Trump and Paul Ryan on the right. While the US is currently wrestling with right-wing insurrectionism (and this meeting happened even before neo-Nazis marched in Charlottesville, VA and the President assured us that some of them were nice people) it’s important to remember that anti-institutionalism comes in a variety of flavors. (One researcher at the meeting observed that the common ground of insurrectionism may explain the otherwise weird phenomenon of Bernie supporters going on to support Trump.)

Mapping politicians on the twin axes of left/right and institutionalist/insurrectionist

Another idea that came up was that the categories of institutionalism and insurrectionism are fluid and changing, because revolutionaries quickly become institutions. When Google came into the search engine game, it was a revolutionary new player, upending Yahoo!, Lycos, Alta Visa and others. Twenty years later, it’s one of the most powerful corporate and civic actors in the world. Understanding that successful revolutions tend to beget institutions is helpful for understanding insurrectionism as a political pole. Some insurrectionists will win their battles and may find themselves defending the institutions they build. (I think fondly of my friend Joi Ito, who spent years as an enfant terrible in Japanese internet circles before becoming surprisingly acceptable as the director of the MIT Media Lab.) Others will hold onto insurrectionism even when their side wins – my friend Sami ben Gharbia moved seamlessly to being a critic of the Ben Ali government in Tunisia to critiquing the new government the Arab Spring brought to power.

Understanding that revolutions beget new institutions made me think of Pierre Rosanvallon’s work on Counterdemocracy, which isn’t as well known in the US as it should be. Rosanvallon observes that, during the French Revolution, a slew of new institutions sprang up to ensure the new leaders stayed true to their values. This wasn’t always a pretty picture – the Terror came in part from the institutions Rosanvallon explores – but the idea that democracy needs to be counterbalanced and bolstered by forces of oversight, prevention and judgement is one worth considering as we examine modern-day institutions and their shortcomings.

When a disruptive entity like Google or Facebook becomes an institution, it’s incumbent on us to build systems that can monitor their behavior and hold them accountable. It’s rare that existing regulatory structures are well-equipped to serve as counter-democratic institutions to counterbalance the new ways in which they work. As a result, there’s at least two ways look for change as an insurrectionist: you can identify institutions that aren’t working well and strive to replace them with something better, or you can dedicate yourself to monitoring and counterbalancing those institutions, building counterdemocratic institutions in the process.

What does this mean for the fine folks working with Knight on news and trust? The press is a key part of counterdemocracy. It needs to hold power responsible. As democratic institutions of power change, counterdemocratic systems have to change as well – nostalgia for how the press used to work is less helpful than understanding the way in which political and civic power are changing, so that the press can continue to act as an effective counterweight. The good news for me was that the folks at Knight are emphatically not holding onto a nostalgic view of the press, trying to return to a Watergate golden age. The bad news? Just like the rest of us, they don’t know what the shape of this emergent new civics is either.

Here’s a prettier version of this paper, hosted my MIT’s DSpace archive. What follows below is a less pretty, but web-friendlier version.

Mistrust, efficacy and the new civics:

understanding the deep roots of the crisis of faith in journalism

Ethan Zuckerman, Center for Civic Media, MIT Media Lab

August 2017

Executive summary

Current fears over mistrust in journalism have deep roots. Not only has trust in news media been declining since a high point just after Watergate, but American trust in institutions of all sorts is at historic lows. This phenomenon is present to differing degrees in many advanced nations, suggesting that mistrust in institutions is a phenomenon we need to consider as a new reality, not a momentary disruption of existing patterns. Furthermore, it suggests that mistrust in media is less a product of recent technological and political developments, but part of a decades-long pattern that many advanced democracies are experiencing.

Addressing mistrust in media requires that we examine why mistrust in institutions as a whole is rising. One possible explanation is that our existing institutions aren’t working well for many citizens. Citizens who feel they can’t influence the governments that represent them are less likely to participate in civics. Some evidence exists that the shape of civic participation in the US is changing shape, with young people more focused on influencing institutions through markets (boycotts, buycotts and socially responsible businesses), code (technologies that make new behaviors possible, like solar panels or electric cars) and norms (influencing public attitudes) than through law. By understanding and reporting on this new, emergent civics, journalists may be able to increase their relevance to contemporary audiences alienated from traditional civics.

One critical shift that social media has helped accelerate, though not cause, is the fragmentation of a single, coherent public sphere. While scholars have been aware of this problem for decades, we seem to have shifted to a more dramatic divide, in which people who read different media outlets may have entirely different agendas of what’s worth paying attention to. It is unlikely that a single, authoritative entity – whether it is mainstream media or the presidency – will emerge to fill this agenda-setting function. Instead, we face the personal challenge of understanding what issues are important for people from different backgrounds or ideologies.

Addressing the current state of mistrust in journalism will require addressing the broader crisis of trust in institutions. Given the timeline of this crisis, which is unfolding over decades, it is unlikely that digital technologies are the primary actor responsible for the surprises of the past year. While digital technologies may help us address issues, like a disappearing sense of common ground, the underlying issues of mistrust likely require close examination of the changing nature of civics and public attitudes to democracy.

Introduction

The presidency of Donald Trump is a confusing time for journalists and those who see journalism as an integral component of a democratic and open society.

Consider a recent development in the ongoing feud between the President and CNN. On July 2nd, Donald Trump posted a 28 second video clip to his personal Twitter account for the benefit of his 33.4 million followers. The video, a clip from professional wrestling event Wrestlemania 23 (“The Battle of the Billionaires”), shows Trump knocking wrestling executive Vince McMahon to the ground and punching him in the face. In the video, McMahon’s face is replaced with the CNN logo, and the clip ends with an altered logo reading “FNN: Fraud News Network”. It was, by far, Trump’s most popular tweet in the past month, receiving 587,000 favorites and 350,000 retweets, including a retweet from the official presidential account.

CNN responded to the presidential tweet, expressing disappointment that the president would encourage violence against journalists. Then CNN political reporter Andrew Kaczynski tracked down Reddit user “HanAssholeSolo”, who posted the video on the popular Reddit forum, The_Donald. Noting that the Reddit user had apologized for the wrestling video, as well as for a long history of racist and islamophobic posts, and agreed not to post this type of content again, Kaczynski declined to identify the person behind the account. Ominously, he left the door open: “CNN reserves the right to publish his identity should any of that change.” The possibility that the video creator might be identified enraged a group of online Trump supporters, who began a campaign of anti-CNN videos organized under the hashtag #CNNBlackmail, supported by Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, who took to Twitter to speculate on the crimes CNN might have committed in their reportage. By July 6th, Alex Jones’s Infowars.com was offering a $20,000 prize in “The Great CNN Meme War”, a competition to find the best meme in which the President attacked and defeated CNN.

It’s not hard to encounter a story like this one and wonder what precisely has happened to the relationship between the press, the government and the American people. What does it mean for democracy when a sitting president refers to the press as “the opposition party”? How did trust in media drop so low that attacks on a cable news network serve some of a politician’s most popular stances? How did “fake news” become the preferred epithet for reporting one political party or another disagrees with? Where are all these strange internet memes coming from, and do they represent a groundswell of political power? Or just teenagers playing a game of one-upsmanship? And is this really what we want major news outlets, including the Washington Post, the New York Times and CBS, to be covering?)

These are worthwhile questions, and public policy experts, journalists and academics are justified in spending significant time understanding these topics. But given the fascinating and disconcerting details of this wildly shifting media landscape, it is easy to miss the larger social changes that are redefining the civic role of journalism. I believe that three shifts underlie and help explain the confusing and challenging landscape we currently face and may offer direction for those who seek to strengthen the importance of reliable information to an engaged citizenry:

– The decline of trust in journalism is part of a larger collapse of trust in institutions of all kinds

– Low trust in institutions creates a crisis for civics, leaving citizens looking for new ways to be effective in influencing political and social processes

– The search for efficacy is leading citizens into polarized media spaces that have so little overlap that shared consensus on basic civic facts is difficult to achieve

I will unpack these three shifts in turn, arguing that each has a much deeper set of roots than the current political moment. These factors lead me to a set of question for anyone seeking to strengthen the importance of reliable information in our civic culture. Because these shifts are deeper than the introduction of a single new technology or the rise of a specific political figure, these questions focus less on mitigating the impact of recent technological shifts and more on either reversing these larger trends, or creating a healthier civic culture that responds to these changes.

What happened to trust?

Since 1958, the National Election Study and other pollsters have asked a sample of Americans the following question: “Do you trust the government in Washington to do the right thing all or most of the time?” Trust peaked during the Johnson administration in 1964, at 77%. It declined precipitously under Nixon, Ford and Carter, recovered somewhat under Reagan, and nose-dived under George HW Bush. Trust rose through Clinton’s presidency and peaked just after George W. Bush led the country into war in Iraq and Afghanistan, collapsing throughout his presidency to the sub-25% levels that characterized Obama’s years in office. Between Johnson and Obama, American attitudes towards Washington reversed themselves – in the mid 1960s, it was as difficult to find someone with low trust in the federal government as it is difficult today to find someone who deeply trusts the government.

Data from Gallup, derived largely from the National Election Survey

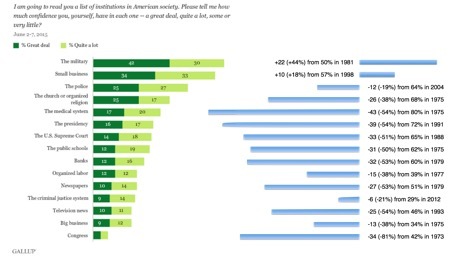

Declining trust in government, especially in Congress – the least trusted branch of our tripartite system – is an old story, and generations of politicians have run against Washington, taking advantage of the tendency for Americans to re-elect their representatives while condemning Congress as a whole. What’s more surprising is the slide in confidence in institutions of all sorts. Trust in public schools has dropped from 62% in 1975 to 31% now, while confidence in the medical system has fallen from 80% to 37% in the same time period. We see significant decreases in confidence in organized religion, banks, organized labor, the criminal justice system and in big business. The only institutions that have increased in trust in Gallup’s surveys are the military, which faced Vietnam-era skepticism when Gallup began its questioning, and small business, which is less a conventional institution than the invitation to imagine an individual businessperson. With the exception of the military, Americans show themselves to be increasingly skeptical of large or bureaucratic institutions, from courts to churches.

Data on the left from Gallup. On the right are my calculations of drops in trust, based on Gallup data.

American media institutions have experienced the same decades-long fall in trust. Newspapers were trusted by 51% of American survey respondents in 1979, compared to 20% in 2016. Trust in broadcast television peaked at 46% in 1993 and now sits at 21%. Trust in mass media as a whole peaked at 72% in 1976, in the wake of the press’s role in exposing the Watergate scandal. Four decades later, that figure is now 32%, less than half of its peak. And while Republicans now show a very sharp drop in trust in mainstream media – from 32% in 2015 to 14% in 2016, trust in mass media has dropped steadily for Democrats and independents as well.

In other words, the internet and social media has not destroyed trust in media – trust was dropping even before cable TV became popular. Nor is the internet becoming a more trusted medium than newspapers or television – in 2014, 19% of survey respondents said they put a great deal of trust in internet news. Instead, trust in media has fallen steadily since the 1980s and 1990s, now resting at roughly half the level it enjoyed 30 years ago, much like other indicators of American trust in institutions.

It’s not only Americans who are skeptical of institutions, and of media in particular. Edelman, a US-based PR firm, conducts an annual, global survey of trust called Eurobarometer, which compares levels of trust in institutions similar to those Gallup asks about. The 2017 Eurobarometer survey identifies the US as “neutral”, between a small number of high trust countries and a large set of mistrustful countries. (Only one of the five countries Eurobarometer lists as highly trusting are open societies, rated as “free” by Freedom House: India. The other four – China, Indonesia, Singapore and the United Arab Emirates, are partly free or not free. Depressingly, there is a discernable, if weak, correlation (R2=0.162) between more open societies and low scores on Edelman’s trust metric.) As in the US, trust in media plumbed new depths in Eurobarometer countries, reaching all time lows in 17 of the 28 countries surveyed and leaving media contending with government as the least trusted set of institutions (business and NGOs rate significantly higher, though trust in all institutions is dropping year on year.)

So what happened to trust?

By recognizing that the decrease in trust in media is part of a larger trend of reduced trust in institutions, and understanding that shift as a trend that’s unfolded over at least 4 decades, we can dismiss some overly simplistic explanations for the current moment. The decline of trust in journalism precedes Donald Trump. While it’s likely that trust in media will fall farther under a government that presents journalists as the opposition party, Trump’s choice of the press as enemy is shrewd recognition of a trend already underway. Similarly, we can reject the facile argument that the internet has destroyed trust in media and other institutions. Even if we date broad public influence of the internet to 2000, when only 52% of the US population was online, the decline in trust in journalism began at least 20 years earlier. If we accept the current moment as part of a larger trend, we need a more systemic explanation for the collapse of trust.

Scholars have studied interpersonal trust – the question of how much you can trust other individuals in society – for decades, finding “>”participatory politics”, sharing civic information online, discussing social issues in online fora, making and sharing civic media. And while young people may not be volunteering for political campaigns, they are volunteering at a much higher rate than previous generations, looking for direct, tangible ways they can participate in their communities.

We are beginning to see new forms of civic participation that appeal to those alienated from traditional political processes. One way to understand these methods is as levers of change. When people feel like they are unlikely to move formal, institutional levers of change through voting or influencing representatives, they look for other levers to make movement on the issues they care about.

In his 1999 book, Code and Other Laws of Cyberspace, Lawrence Lessig argues that there are four primary ways societies regulate themselves. We use laws to make behaviors legal or illegal. We use markets to make desirable behaviors cheap and dangerous ones expensive. We use social norms to sanction undesirable behaviors and reward exemplary ones. And code and other technical architectures make undesirable actions difficult to do and encourage other actions. Each of the regulatory forces Lessig identifies can be turned into a lever of change, and in an age of high mistrust in institutions, engaged citizens are getting deeply creative in using the three non-legal levers.

In the wake of Edward Snowden’s revelations of widespread NSA surveillance of communications, many citizens expressed fear and frustration. The Obama administration’s review of the NSA’s programs made few significant changes to domestic spying policies. Unable to make change through formal government processes, digital activists have been hard at work building powerful, user-friendly tools to encrypt digital communications like Signal, an unstable individual took up arms to “self-investigate” the controversy.

Hallin’s spheres suggests we question whether we are encouraged to discuss a wide enough range of topics within the sphere of legitimate controversy. The problem we face now is one in which dialog is challenging, if not impossible, because one party’s sphere of consensus is the other’s sphere of deviance and vice versa. Our debates are complicated not only because we cannot agree on a set of shared facts, but because we cannot agree what’s worth talking about in the first place. When one camp sees Hillary Clinton’s controversial email server as evidence of her lawbreaking and deviance (sphere of consensus for many on the right) or as a needless distraction from more relevant issues (sphere of deviance for many on the left), we cannot agree to disagree, as we cannot agree that the conversation is worth having in the first place.

Much as there is no obvious, easy solution to countering mistrust in institutions, I have no panaceas for polarization and echo chambers. Still, it’s worth identifying these phenomena – and acknowledging their deep roots – as we seek solutions to these pressing problems. It is worth noting that the research Benkler’s and my team carried out suggests the phenomenon of asymmetric polarization – in our analysis, those on the far right are more isolated in terms of viewpoints they encounter than those on the far left. There’s nothing in our research that suggests the right is inherently more prone to ideological isolation. By understanding how extreme polarization has developed recently, it might be possible to stop the left from developing a similar echo chamber. Our research also suggests that the center right has a productive role to play in building media that appeals to an insurrectionist and alienated right-leading audience, which keeps those important viewpoints in dialog with existing communities in the left, center and right.

Fundamentally, I believe that the polarization of dialog in the media is a result both of new media technologies and of the deeper changes of trust in institutions and in how civics is practiced. The Breitbartosphere is possible not just because it’s easier than ever to create a media outlet and share viewpoints with the like-minded. It’s possible because low trust in government leads people to seek new ways of being engaged and effective, and low trust in media leads people to seek out different sources. Making and disseminating media feels like one of the most effective ways to engage in civics in a low-trust world, and the 2016 elections suggest that this civic media is a powerful force we are only now starting to understand.

Closing questions

I want to acknowledge that this paper may stray far from the immediate challenges that face us around issues of information quality, in the service of seeking for their deeper roots. My questions follow in the same spirit. For the most part, these are questions to which I don’t have a good answer. Some are active research questions for my lab. My fear is that we may have to address some of these underlying questions before tackling tactical questions of how we should best respond to immediate challenges to faith in journalism.

Trust:

– How long does it take to recover trust in an institution that has failed? What are examples of a mistrusted institution regaining public trust?

– Is the fall in institutional trust an independent or a joint phenomenon – i.e., does losing trust in Congress lessen our trust in the Supreme Court or the medical system

– Is trust in news media higher or lower in countries with strong public/taxpayer supported media? Does trust correlate positively or negatively to ad support? Privacy-invading tracking and targeting?

– If people don’t trust institutions, who or what do they trust? How do those patterns differ for more trusting elites and for the broader population?

Participation:

– What forms of participation (from the traditional, like voting, to the non-traditional, like making CNN-bashing memes) are indicators of future civic engagement? Should we be encouraging and celebrating a broader range of civic participation amongst youth? Amongst groups that see themselves alienated from conventional politics?

– Should media attempt to explain and engage audiences more deeply in institutional politics? Will acknowledging the limits of existing institutional politics restore trust in journalism, or damage trust in government?

– Should media celebrate and promote new forms of civic engagement? Will this further decrease trust in institutions? Increase a sense of citizen efficacy?

– What would media designed for increased public participation look like? Are there models in the advocacy journalism space, or in solutions journalism, constructive journalism or other movements?

Polarization:

– Is it reasonable to expect Americans to rely on a single, or small set, of professional media sources that report a relatively value-neutral set of stories? Or is this goal of journalistic non-partisanship no longer a realistic ideal?

– Could taxpayer-sponsored media serve a function of anchoring discourse around a single set of facts? Or will public media be inherently untrustworthy to some portion of American voters? Why does public media seem to work well in other low-trust nations but not in the US?

– Is there a role for high-quality, factual but partisan media that might reach audiences alienated from mainstream media?

– Should media outlets learn from what’s consensus, debatable and deviant in other media spheres and modify coverage to intersect with reader’s spheres? Is shifting the boundaries of these spheres part of how civics is conducted today?

Ethan Zuckerman's Blog

- Ethan Zuckerman's profile

- 21 followers