Who Deserves Pages and Who Doesn't?

Back Story

At some point while Roy Thomas was Editor in Chief Marvel Comics began giving original artwork to the creative people who had participated in the creation of the pages. That would have been in 1973 or thereabouts.

I wasn't there. I started at Marvel Comics as associate editor on the first working day of January 1976. Before that I had done a freelance job or three, I think in 1974 or 1975, but I lived 400 miles away in Pittsburgh and worked through the mail, so I wasn't exactly on top of what was going on in the office.

As I've said elsewhere in this blog, it seemed that no one cared what the companies did with the original art during the 1960's and before. Pages were given away, thrown away or stored away and there was no hue and cry about it. By the early 1970's however, creative people had a new awareness of an interest in original art.

Here's my theory:

In the elder days of the comic book industry, until the 1960's, comics were almost entirely made for children, or on the high end, adolescents. Yes, of course there were some exceptions, but not many, and if you were an adult who appreciated the medium or, perhaps, enjoyed the more sophisticated offerings, you kept that to yourself. Or risked ridicule.

From what I've heard and seen from the old guard people I worked with over the years, the publishers and professionals generally had indifference toward the audience. Distribution was through newsstands or subscription. There was virtually no contact between creators and readers. Who cared what six-year-olds thought, anyway?

Professionals had reactions ranging from bemusement to disdain for the older readers who demonstrated their existence somehow, say by writing a letter of comment. As late as the mid-to-late sixties, the people at DC Comics I worked with, and for, insisted that comic books were read by six-to-eight-year-olds plus a smattering of older, arrested-development geeks.

During the 1950's the comic book business suffered a slow decline for lots of reasons we can talk about later. One result of that was that relatively few new creators entered the business during that decade, especially toward the end of it. If a publisher needed an artist, there were plenty available who needed work. No need to train new people. The average age of the creators and publishing people crept upward.

So what we had here was, to a great extent, increasingly older men (and a few women) making what they thought was throw-away entertainment for little kids. The originals, which were produced by the ton, were considered as throw-away as the end product.

In fact, and here's a kicker for you—an artist or writer expressing any interest in the originals from a book they'd worked on would have risked ridicule. Oh, no…! You're not one of those geeks, are you?!

And here's the disclaimer. Of course, many, many of the artists and writers were "geeks." But secretly, for the most part. Geeks like us, I mean. People who loved what they did, loved the medium, loved great comics. You just didn't say it or show it too obviously back in those days.

Julie Schwartz was one of us. Comics-loving geek through and through. But remember the time he was on that talk show with Stan and spoke of comics with disdain: "…something to read on the toilet," etc. Acting as if working in comics was just a job, a way to pay the bills. Remember that? Julie Schwartz, hiding his true nature on national TV so as to preserve the dignified "adult" image that people of that generation, the one before mine, thought was important. Really important.

But we knew, didn't we? Saw right through the guy. He probably had a Superman tee-shirt on under his pinpoint Oxford.

Anyway….

Around the beginning of the sixties, things started to change. Marvel was a leader in the revolution. Not the only one. Warren was right up there. And, secretly, Julie.

At Marvel, geek-like-us Stan tried writing comics that he thought would appeal to guys like him, like you, like me. Why not? Marvel was dying. The industry was slowly dying. Why not give it a try?

And we all know what happened next. The audience expanded. The demographic shifted upward in age. College kids were reading comics, and suddenly it was cool and hip. Part of that was the cultural revolution and counter-culture bent of the '60's, but part of it was because the comics were good.

We started coming out of the closet.

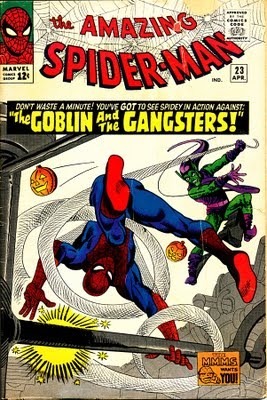

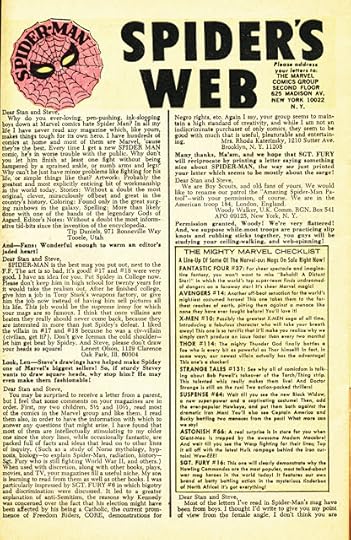

Stan published the addresses of correspondents whose letters were used in the lettercols. My childish, embarrassing letter appears in Amazing Spider-Man #23.

1965

1965

Click to enlarge

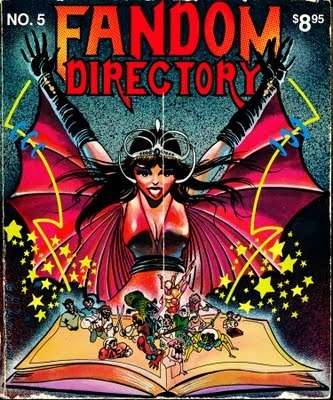

Click to enlargeFans—and that's what we were and are—started getting in touch with each other. At one point, wasn't someone publishing a Fandom Directory? I think I have a couple of those around here somewhere.

Aha!!

People started organizing get-togethers. Conventions. And generally, the organizers weren't disaffected promoters just trying to make a buck cashing in on our fannishness, they were fans themselves, first and foremost. We have met the organizers and they are us.

I think one of the first conventions in New York City was organized by Marv Wolfman and Len Wein. Think about that. They are us. Big time.

I think they told me Steve Ditko was among the professional guests. Possibly his one and only such appearance. Wow.

So, fans and pros started getting together. Not only at cons. All-time great inker Frank Giacoia used to tell me that Marv and Len would show up at his house sometimes to gawk at the pages on his board. That was new. Such things didn't happen often in the elder days.

So…suddenly pros found themselves face to face with fans and discovered that many, if not most, were substantially older than six. And, in fact, were publicly, out-of-the-closet exactly what they, the pros, were secretly. Geeks.

Who cared what the fans thought? Pros did, and do.

Professional creators also became aware that some fans were real adults with real money. Collectors, in fact.

Slowly the little light bulb went on that maybe those original art pages were worth something. And if the companies were giving them, or worse, throwing them away, well…gee. Creators started thinking, more and more, how about giving them to us?!

Then it got weird. The companies, which had been so careless and free with the original art, began to worry about it. If the stuff had value, well…gee.

Legal chimaeras began rearing up. Wouldn't giving creators original art back imply that it was "theirs" all along, and perhaps help them assert claims of ownership of the characters and the underlying rights? What if they used the pages to publish knock-offs of the comics, or to make money in other ways? Like selling prints, or charging people to come into a gallery to view the art, or…those revenues should belong to the company! said the Legal Tweezers. Those pages are assets of the corporation! Good grief.

My favorite derivative chimaera is this one: the company can't give away assets without risking exposure to a shareholders' derivative suit.

Help me, Rhonda.

Meanwhile, it got interesting. Enough of the old guard creators had retired, died, or like Alvin Schwartz, for instance, moved on to better paying non-comics work that during the early to mid-sixties, when the Marvel-led, TV-show-fed, counter-culture-revolutionary-sixties comics boom was developing, the companies had to start hiring new people! Among the first of that new wave were, in no particular order, Roy Thomas, Denny O'Neill, E. Nelson Bridwell, Neal Adams, Archie Goodwin and me. A couple of years later, Len and Marv, remember them? broke in.

Fans were becoming pros! Infiltration! But we in the vanguard unabashedly showed our passion for our work and the business….

The companies were slow to adjust, in spite of the influx of us geeks. Len and Marv told me that among their early jobs at DC Comics was destroying original art that had piled up. They said they once salvaged shopping bags full of the stuff, escaped with it and sprung for cabs back to their homes in Queens because it would have been impossible to carry it all on the subway. Paying for a cab to Queens in those days of lousy compensation was a desperate act, but they were desperate men, apparently.

I don't know what struggles Roy went through to get Marvel Comics' first artwork return policy enacted, but judging from some of the related struggles I had with bone-head business types and Legal Tweezers, I imagine it was no cakewalk.

Anyway….

Roy's policy provided that the majority of the pages went to the penciler, a lesser number to the inker and a still-smaller number, generally two pages from an average book, to the writer.

The writer?

Well, Roy of course, is a writer, and I suppose he reasoned that the writer lays the foundation for the art, and writers love original art as much as the next geek. By the way, the penciler had first choice, the inker had second choice and the writer got what was left.

The artists were generally against writers getting pages. Among the many maelstroms I inherited when I took over as EIC on the first working day of January 1978 was the War Over the Writers' Share. I found in a file the other day long impassioned letters from Claremont, Moench, Sinnott, Leialoha, McLeod and Austin, plus a note from Stan. I'm still trying to find Mantlo's letter on the subject. Details tomorrow.

Rooting Out Corruption at Marvel Part 5 Starring Me as the Perp

Originals Sin

Joe Sinnott, great artist and outstanding human who mostly inked for Marvel for centuries, I think, was a gentlemanly but ardent advocate for the return of originals. Joe, who is not one to complain, who had soldiered on heroically through bad times and worse times until better days finally came, told me that he, in all his decades of service had never gotten a splash page of a book. Even after I eliminated the penciler-chooses-first policy and we went to a random distribution. (I know, I'm giving away part of the ending of the whole tale, but it's not like that was a state secret anyway.) Joe still managed to never randomly get a splash page. Ever. For years. Bad luck of the draw.

In those stone-age days, the way we divided up the pages of a book was this: we had a deck of playing cards numbered on the faces with marker. If, say, the book was 22 pages, the artwork return assistant would take cards one through twenty-two, shuffle and deal them face down into stacks representing each creators' share. Each guy got the pages corresponding to the numbers of the cards in his stack.

So, one time, after getting off the phone with Joe, I went to the artwork return office, chased the assistant out of the room, shuffled and dealt the cards for a John Buscema/Joe Sinnott book and, glorioski, look what happened, Joe got the splash! I may have dealt that card from the bottom of the deck….

I confessed to John later. He was okay with my crime. He'd gotten the splash page every single other time and he didn't mind Joe getting a break. I should have asked him first, of course, but he was cool.

NEXT: Many Happy Returns and Some Unhappy People

Bonus!

Pictures that turned up

HEROES FOR HOPE CHECK PRESENTATIONPictured are (from left): Spider-Man, Jim Galton, Jim Shooter and Ann Nocenti with Sarita Gupta and Patricia Hunt of the American Friends service Committee.

HEROES FOR HOPE CHECK PRESENTATIONPictured are (from left): Spider-Man, Jim Galton, Jim Shooter and Ann Nocenti with Sarita Gupta and Patricia Hunt of the American Friends service Committee.

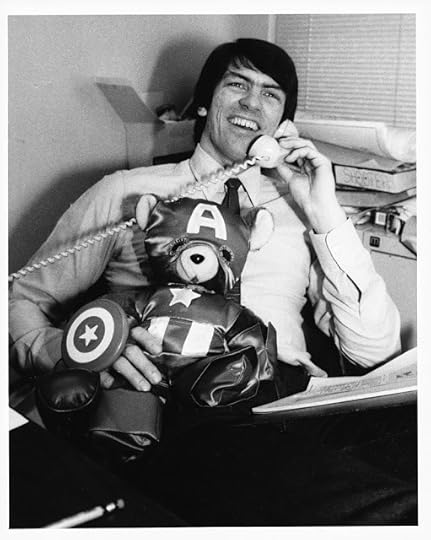

BEAR WITH ME

BEAR WITH ME

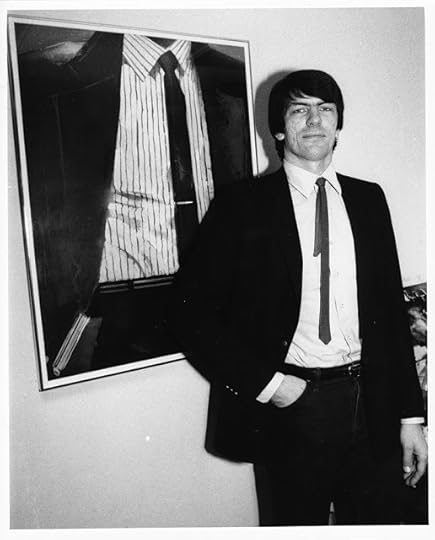

GOOD LIKENESS?

GOOD LIKENESS?

Published on September 15, 2011 13:15

No comments have been added yet.

Jim Shooter's Blog

- Jim Shooter's profile

- 85 followers

Jim Shooter isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.