Why Zombies are less about eating brains and more about having them.

Okay, I am writing a book about zombies. They're not called that, but they are animated dead hungry for human flesh. It has a fairly unique setting, so I'm not worried that it is too similar to the bevy of other zombie books out there. But it is sort of embarrassing to tell people about. I would like to say "But don't worry, it's good," but I have to admit that I wouldn't know if it wasn't. I can say, though, that I'm approaching the subject as seriously as I can.

We all know there are a lot of bad zombie books and movies out there, and if it weren't for vampires they would be the most overused trope of horror in the last 10 years. The trope has been abused (fast zombies? Get the fuck out), degraded (zombie strippers? What are you doing?), and undeveloped (zombies as generic bad guys.) Yawn.

This is risking the "no true Scotsman" fallacy, but those aren't zombies. Not really. Zombies need to be slow, they need to multiply and they need to come back from the dead. It isn't exactly breaking new ground to say that zombies serve as a metaphor, but I'd say, rather, that they serve as the metaphor. The metaphor of inevitability.

I would argue further that this comes, most evidently, from existentialism. Sartre and Camus, among others, wrote about the importance of human individuality and freedom. (That is an embarrassingly superfluous definition, but to get into depth this would take thousands of pages of discussion.)

The tenets of the existentialists were became applied concepts in the Theatre of the Absurd. (The distinction is really not as neat as that. Sartre and Ionesco purportedly hated each other. More so than most labels, grouping these writers into one genre is painting with really broad brush strokes.) Writers like Beckett, Albee, Stoppard, Pinter and, most importantly for this discussion, Euegene Ionesco found a better well to discuss the human condition–by showing us, rather than telling us.

Consider this cherry-picked quote from the wikipedia entry on plots from Theatre of the Absurd: "Often there is a menacing outside force that remains a mystery" A little later, it adds "Absence, emptiness, nothingness, and unresolved mysteries are central features in many Absurdist plots" That could describe most horror movies, but of course anything that vague can be mis-applied.

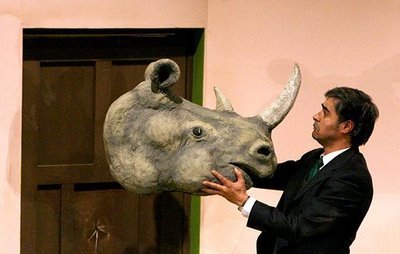

More specifically, Ionesco explored the theme of death by writing a play about a corpse growing larger and larger. Most importantly at all he wrote "The Rhinoceros." In the play, people start, inexplicably, turning into rhinos. The protagonist is the only one who does not change; he is our everyman lens into the story. Ionesco was, probably, writing about the rise of Communism, Facism, and Nazism, but you could replace every instance of the word "rhinoceros" with "zombie" and it wouldn't lose its core meaning.

Albee's "Zoo Story," again according to wikipedia, "explores themes of isolation, loneliness, miscommunication as anathematization, social disparity and dehumanization in a commercial world." That's not too far off from Romero's Dawn of the Dead.

So, hell yes, I would argue that zombies are descended from the smokey parlours of 1950′s France. "Hell is other people" has one meaning in No Exit, but quite another in Night of the Living Dead. Absurdists began the process of showing these stories, creating improbable scenarios. And zombies have succeeded them; it doesn't get much more improbable than the dead rising and coming after you for their midnight snack.

This doesn't mean that reading World War Z is the same as reading The Plague, but they're not as far off as you might suppose.