Meta-analysis: Impact of carbohydrate vs. fat calories on energy expenditure and body fatness

Sometimes, a meta-analysis (quantitative study of studies) is just what the doctor ordered to inoculate us against the shortcomings of our own cognition. When a topic has been studied extensively and it has produced many studies of varying quality, this lends itself to incorrect conclusions because we can find studies to support almost any belief. This is problematic because we naturally tend to gravitate toward evidence that reinforces pre-existing beliefs, and away from evidence that challenges beliefs. Called confirmation bias, this phenomenon afflicts all of us and has to be actively managed if we want to arrive at reliable knowledge. Systematically examining a body of evidence and integrating it mathematically is a useful tool for combating this bias. A new meta-analysis examines the effect of carbohydrate vs. fat calories on energy expenditure and body fatness, giving us the most objective view of this question to date.

The study

Recently, Drs. Kevin Hall and Juen Guo published what I believe is the first meta-analysis of controlled feeding studies that compared diets of equal calorie content but differing in carbohydrate and fat content (1). They only considered studies in which all food was provided by researchers and protein intake was held constant between diets. Their outcomes were energy expenditure and body fatness.

The results

They identified 28 studies that met their criteria for energy expenditure. Combining the data of these 28 studies, they found that calorie-matched diets predominating in fat vs. carbohydrate have almost identical effects, but higher-carbohydrate diets do lead to a slightly higher energy expenditure. This difference was statistically significant but of little medical or practical relevance, since it only amounted to 26 Calories per day. This slightly higher energy expenditure is consistent with the fact that the metabolism of carbohydrate is slightly less efficient than the metabolism of fat, meaning that a bit more energy is wasted*.

Examining the data, the paper’s result is not hard to believe because only 8 of the 28 studies reported that lower-carbohydrate diets led to a higher energy expenditure than higher-carbohydrate diets, and among those 8, the results were only statistically significant in four. In contrast, 20 studies reported higher energy expenditure with higher-carbohydrate diets, and that was statistically significant in 14. One can choose individual studies that support either belief, but the overall evidence suggests that the relative carbohydrate and fat content of the diet has little impact on energy expenditure.

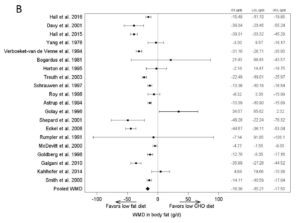

Onward to body fatness. Hall and Guo identified 20 controlled feeding studies that reported changes in body fatness on equal-calorie diets differing in fat and carbohydrate content. Echoing the energy expenditure finding, they found that diets predominating in carbohydrate or fat have similar effects on body fatness. Yet higher-carbohydrate diets do lead to a slightly greater loss of body fat per calorie, amounting to a 16 gram per day difference. This is actually a larger difference than one would predict from the difference in energy expenditure, which would only be 2.8 g/day.

Discussion

Given this new meta-analysis, I think it’s now fairly safe to say that in a general sense, equal calories from fat and carbohydrate have similar effects on energy expenditure and body fatness, with a possible small “metabolic advantage” for higher-carbohydrate diets. This doesn’t imply very much about the real-world effectiveness of low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets because it doesn’t factor in free-living calorie intake, but it is relevant to certain popular theories about how those diets work. The upshot is that you shouldn’t expect altering the carbohydrate-to-fat ratio of your diet to work magic on your metabolic rate, but rather you should choose a diet that controls your calorie intake effectively and sustainably.

It is no longer tenable to suggest that carbohydrate per se reduces energy expenditure and causes the accumulation of body fat independent of calorie intake. This idea was never very well rooted in evidence, but now that we have a meta-analysis it is clear that it resulted from confirmation bias.

This meta-analysis leaves many questions unanswered. Is the same effect observed during weight gain, weight maintenance, weight loss, and weight loss maintenance, or could the ratio of carbohydrate to fat matter in these scenarios**? Is the effect observed equally at moderate macronutrient ratios and at the extremes? We have individual studies that address these questions, but no meta-analysis yet.

Hall and Guo’s paper is not just a meta-analysis. It’s a review of obesity energetics, body weight regulation, and their relationship to diet composition. It is hands-down the single most informative paper I’ve encountered for explaining the relationship of energy intake and expenditure to body fatness, and the big-picture view of how the body’s energy control systems work. It comes from a research group that is at the leading edge of these questions. It took me years of study to formulate the high-level perspective that you can now get from an hour of reading (1). It also dovetails nicely with chapters 1, 6, and 7 of The Hungry Brain.

* I’m not certain that this explains the higher energy expenditure; I’m just suggesting that it’s an obvious possibility.

** A study by Dr. David Ludwig’s group suggests the possibility that the outcome could be different in the context of weight loss maintenance (2). I doubt there are enough studies on this to support a proper meta-analysis.

Tweet

Share on Tumblr

Stephan Guyenet's Blog

- Stephan Guyenet's profile

- 40 followers