Kevin Manus-Pennings Skids in Sideways

Please welcome Kevin Manus-Pennings to Skidding in Sideways. Kevin is my friend and writing mentor. When I graduated from college and got a job as a proofreader and general publishing flunky, I confessed my desire to write a novel one day, and Kevin, who was a real editor, began sending me daily writing tips. He made me realize there was a bit of science to the art of writing. His new book A Shore Too Far (Daughters of Damendine) was released just this week, so if you love fantasy novels, please check it out.

was released just this week, so if you love fantasy novels, please check it out.

The Inheritance of Genius

I think most of my friends would tell you that they knew that I would eventually write a novel. In fact, I think most would mention that they're surprised it took this long. Those childhood friends in Southeast Georgia would remind you that my father was a speed reader who would go to the library with a Xerox box and fill it from whole sections of the library only to return them all read by the end of the week. My father, they would say, loved to talk about stories in the sense of what it meant to make tough decisions, moral decisions, what it meant to make THE right decision.

My childhood friends would point also to my older and younger brothers. The older, who crafted role-playing games around special forces units or espionage, also loved to play fantasy role-playing games, immersing himself in the adventure of the moment. The younger brother read fantasy and science fiction and shaped whole worlds for his own games. All three of us, our friends would say, had large comic book collections, all of them including the morally challenging Uncanny X-men.

My college friends could add further evidence to the indictment. I took so many classes in English that the head of the department felt she had to call me in and remind me that I wouldn't receive any credit for some of them because of the number I had taken. To my friends' dismay, I enjoyed writing literary criticism papers for class and eventually became the fiction editor for the school's literary journal. Yes, my college friends would say, he was destined to write something.

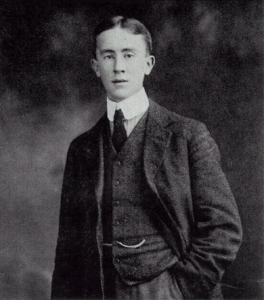

J. R. R. Tolkien in 1911 (Wikimedia Commons)

Despite all these influences, however, it was Tolkien's The Hobbit that set me out the door and to my status today as a novelist (however humble that status may be). When I closed that book in eighth grade, I was conscience of two fundamental realizations. First, The Hobbit did something to me page by page that no other book had ever done. And, perhaps more importantly, those effects had to be the result of specific decisions by the writer, by Tolkien. In other words, literary effect comes from literary choices, strategies, and approaches.

The consequences of these two conclusions are not immediately obvious, but here's the most profound one for my own life, then and now: if literary decisions produce particular effects within a reader, then studying those decisions, identifying them and understanding them, means that they could be reproduced in one's own work. The method's could be borrowed like tools from a neighbor and set to work in one's own projects. From that point on, I began studying every work I encountered to identify how the work affected me and what caused that affect. Like being left an inheritance that is only spelled out in clues, each writer today has a wealth of strategies left him or her by the writers of the past. The hazy arguments about "the muse" or "inspiration" can all be put aside in favor of this arsenal of art if only we spend the time doing an inventory of what we have received.

Tolkien's real genius, and here I mean what his art does better than anyone else's, was world-building, especially in making a world feel large and indescribably old. So now comes the question of how he accomplishes it? Or put another way, what tools has he bequeathed us to achieve that same affect in our readers? I only have partial answers, but more interesting is the question of how many other gems of knowledge line our path that we have not yet learned to see?