Mark Twain’s “A Dying Man’s Confession”: Truth or Tall Tale?

Mark Twain, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, public domain

God! how delicious the memory of it!—I caught him escaping from his grave, and thrust him back into it. – Mark Twain, “A Dying Man’s Confession,” in Life on the Mississippi

Murder and revenge.

These two themes form the warp and weft in “A Dying Man’s Confession,” the most memorable short story in Mark Twain’s Life on the Mississippi. The story spans the globe. It starts a murder in Arkansas during the Civil War and ends in one of the creepiest buildings of Germany history: the Leichenhaus (literally: corpse house) or waiting mortuary. And it contains a forensic method that was very modern for its time.

But are there any kernels of truth in Twain’s story?

A bit of background: the German Leichenhaus

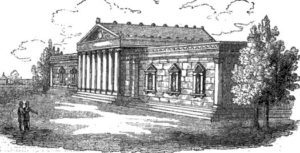

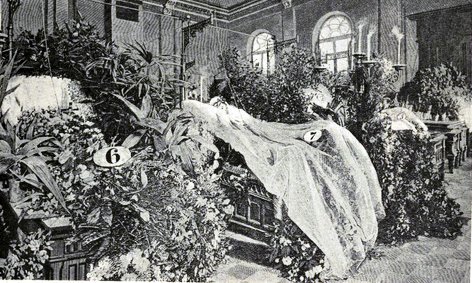

Waiting halls for the dead sprung up throughout Germany in the 19th century, in part due to societal fears of premature burial, and in part due to the medical profession’s argument that decomposition constituted the only sure sign of death. Bodies were laid out in the mortuary halls, in their coffins and covered with shrouds, to await that one sure medical sign before burial. Flowers decked the coffins to offset the odor.

To prevent someone from being buried alive, the mortuary attached rings and cables to the hands of the presumptive dead. If a hand moved, a bell would sound and alert a mortuary attendant, trained to give first aid.

The Munich Leichenhaus. Garner’s Magazine, 1833 (public domain).

Twain in the Munich Leichenhaus

Munich’s Leichenhaus was one of the most famous. Open to the public, it quickly became a tourist attraction. Mark Twain visited on Jan. 4, 1879. His impressions unnerved him:

Toward the end of last year, I spent a few months in Munich, Bavaria…. One day, during a ramble about the city, I visited one of the two establishments where the Government keeps and watches corpses until the doctors decide that they are permanently dead, and not in a trance state. It was a grisly place, that spacious room. There were thirty-six corpses of adults in sight, stretched on their backs on slightly slanted boards, in three long rows—all of them with wax-white, rigid faces, and all of them wrapped in white shrouds. Along the sides of the room were deep alcoves, like bay windows; and in each of these lay several marble-visaged babes, utterly hidden and buried under banks of fresh flowers, all but their faces and crossed hands. Around a finger of each of these fifty still forms, both great and small, was a ring; and from the ring a wire led to the ceiling, and thence to a bell in a watch-room yonder, where, day and night, a watchman sits always alert and ready to spring to the aid of any of that pallid company who, waking out of death, shall make a movement—for any, even the slightest, movement will twitch the wire and ring that fearful bell. I imagined myself a death-sentinel drowsing there alone, far in the dragging watches of some wailing, gusty night, and having in a twinkling all my body stricken to quivering jelly by the sudden clamor of that awful summons!*

The experience sparked a short story.

A Dying Man’s Confession

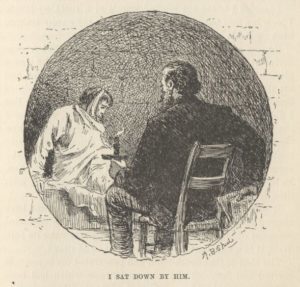

“A Dying Man’s Confession,” which climaxes in the Munich Leichenhaus, begins in Arkansas during the Civil War. A German on his deathbed, whom Twain supposedly met during his Munich travels, narrates the story. He lived in Napoleon, Arkansas with his wife and daughter during the war. But one night, during a burglary, the narrator was chloroformed and his family murdered. One burglar was missing his thumb and was the nicer of the two. His accomplice committed the murder; the thumbless man could only protest.

The burglary was interrupted when the burglars’ company arrived and the captain asked for water; the burglars left with their comrades. The poor narrator found his wife and daughter murdered – along with an important clue: a piece of paper with a thumbprint in their blood. When the narrator discovered that a Captain Blakely and Company C had come through that night, he decided to track down the murderers.

In disguise as a fortune teller, the narrator followed Company C and found a German private missing a thumb. He started telling fortunes, but required his clients to provide their thumbprints first as means for interpreting their future. By careful comparison, he discovered one print that matched the print from his house. The print belonged to another German private, Franz Adler. The narrator tried to murder him and thought he was successful.

In Munich’s Leichenhaus

The narrator returned to Germany and years later began working as a watchman in the Munich Leichenhaus. There the unconceivable happened.

Two years ago—I had been there a year then—I was sitting all alone in the watch-room, one gusty winter’s night, chilled, numb, comfortless; drowsing gradually into unconsciousness; the sobbing of the wind and the slamming of distant shutters falling fainter and fainter upon my dulling ear each moment, when sharp and suddenly that dead-bell rang out a blood-curdling alarum over my head! The shock of it nearly paralyzed me; for it was the first time I had ever heard it.

I gathered myself together and flew to the corpse-room. About midway down the outside rank, a shrouded figure was sitting upright, wagging its head slowly from one side to the other—a grisly spectacle! Its side was toward me. I hurried to it and peered into its face. Heavens, it was Adler!

Adler had survived the narrator’s murder attempt in Arkansas and had also returned to Munich. The narrator refused all first aid and let Adler sink back and die in his coffin.

He ends his “Dying Man’s Confession” with the observation:

It is believed that in all these eighteen years that have elapsed since the institution of the corpse-watch, no shrouded occupant of the Bavarian dead-houses has ever rung its bell. Well, it is a harmless belief. Let it stand at that.

Interior of the Munich Leichenhaus. William Tebbs, Premature Burial and How It Can Be Prevented (1905, public domain).

Truth or Tall Tale?

With Mark Twain, you can’t always tell. Franz Adler and his death in the Leichenhaus are certainly products of Twain’s imagination. But that begs the question of whether any of the bodies in the waiting mortuary ever did come back to life.

Jan Bondeson, a professor at the University of Wales College of Medicine has tracked down stories of premature burial, and in particular, folklore about “resurrections” in the Munich Leichenhaus. He followed the few stories about ringing bells and bodies sitting up in their coffins to their sources, only to find the 19th-century version of fake news.

In the course of the 19th century, how many people did the German waiting mortuaries actually save?

Zero, says Bondeson.

That’s right, none. The 19th-century physician’s diagnosis of death was pretty accurate.

By the 1890s, Germany made the decision to remove the alarm systems from its mortuaries. And we can safely say that Twain’s depiction of Adler ringing his bell crossed the line into the highly improbable.

.

.

Ann Marie Ackermann's Historical True Crime Blog

- Ann Marie Ackermann's profile

- 18 followers