The Face in the Mirror

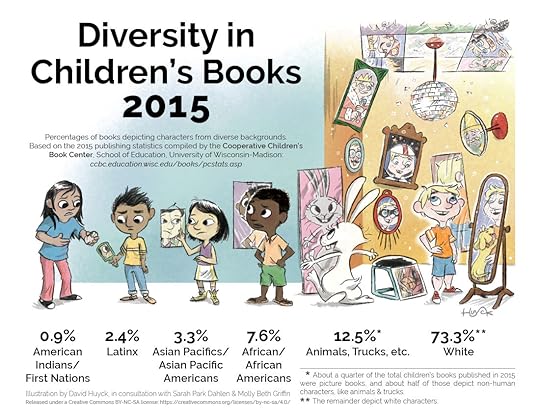

Every year I conduct dozens of presentations in public schools, on college campuses, and at libraries. As a self-published author I am not welcome in certain spaces within the kid lit community, but I am also an independent scholar and my academic credentials open some doors that might otherwise remain closed. I very much appreciate the invitations I do receive to share my particular point of view, and my most popular talk for adults focuses on community-based publishing as one solution to racial discrimination (and, more specifically, anti-Blackness) in the traditional publishing industry. Nothing supports my claim of White supremacy like the illustration commissioned in 2016 by Sarah Park Dahlen at St. Kate’s University. The graphic was inspired by Rudine Sims Bishop’s oft-quoted metaphor of children’s books serving as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.

In addition to providing the 2015 statistics compiled by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, the colorful illustration demonstrates how privilege is bidirectional; you can’t unfairly advantage one individual without simultaneously disadvantaging someone else. Artist David Huyck cleverly positions a White boy—blond-haired and blue-eyed—standing confidently in a room full of mirrors. Each shows him in a different heroic role: king, firefighter, astronaut. By contrast, the children of color and the Indigenous child have only one mirror each; their mirrors diminish in size, corresponding with the limited number of books published about their group. Unlike the White child, these kids are not beaming with joy and/or pride; instead they are downcast and clearly disturbed by the injustice perpetrated against them by those in the US publishing industry.

I have often wished that such a graphic existed for my country of origin. I grew up without “mirror books” and as a result often felt invisible and less valuable than my White peers. When I decided to become a writer at age thirteen, I initially wrote stories about Whites because almost all of the books I consumed featured White protagonists. It has taken years for me to decolonize my imagination, and I doubt I would have become an award-winning Black feminist author and scholar if I had remained in Canada (I left in 1994). I am also critical of my adopted home, but there are opportunities here in the US that simply don’t exist for Blacks in Canada. “The Great White North” prides itself on its diversity (a mosaic rather than a melting pot!), yet the reality often falls far short of the rhetoric around multiculturalism. Canada is a progressive place but it is far from perfect, and its proximity to the US too often results in a kind of smugness in Canadians that I find hard to bear. The apparent disinterest in collecting and publishing diversity data on children’s literature leads me to believe that no one in the Canadian kid lit community feels the effort is warranted. In fact, a 2016 article in School Library Journal celebrated Canadian publishers as leaders in the drive for greater diversity in children’s literature. But is such praise justified? My research on kid lit by and about Black Canadians suggests otherwise. Gathering and illustrating diversity data would provide a much-needed mirror, forcing the Canadian kid lit community to confront not only its successes but also its limitations and failures.

On a recent trip to London, I gave a presentation at the National Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at the University of Roehampton. After my talk, several people asked whether I believed the grim statistics on US kid lit were better or worse in the UK. I told them that I couldn’t say for sure, though I suspect the numbers are worse. What would happen if researchers around the world made a commitment to track diversity in books for young readers? How might scholarship in the field be enhanced by such data? A model for tracking racial diversity already exists—could other countries not replicate (and potentially improve upon and/or extend) the model established by the CCBC at the University of Wisconsin-Madison? What does it say about the profession that so many children’s literature scholars seem content to operate without an accurate understanding of disparities in the representation of their nation’s children? Greater transparency leads to increased trust; if publishers expect the public to believe they are committed to producing inclusive children’s literature, then it’s in their interest to submit their books for annual evaluation.

It’s time to hold up a mirror and take a good, hard look at the global kid lit community. As James Baldwin asserted, “Not everything that is faced can be changed. But nothing can be changed until it is faced.”