A Few Words on Children’s Books

[image error]

So, as part of my degree (Early Childhood Education), I had to take a course in Children’s Literature. Really, not that surprising when you think about it. But what did surprise me was that, on day one of the class, the professor said, “Just because it’s literature for children doesn’t mean it’s good literature.” And when you start to look at the criteria for determining the writing/reading quality of a book, this makes a lot of sense.

Throughout the 20th century, there was much debate among families and educators about what counted as “good” children’s books. As a parent (before I was a teacher), this is a subject that was constantly on my mind in bookstores and school book fairs and libraries. There really is a lot to consider. Is the style age appropriate? Does it fit with where your child is developmentally? Will the content have lasting meaning? Much more than just, “Oh, these pictures are cool.”

And even books are not one size fits all. Autistic children may be very picky readers. They may take issue with everything from the look of the illustrations (are they too bright? too unrealistic? too simple and boring?) to the content of the text (if it makes them sad, will they actually have a breakdown over it?).

When I was younger, it didn’t take me long to figure out that I had a very sensitive constitution, and reading about certain topics were just plain off limits (for example, animal cruelty, war, people with terminal illnesses). This means I do not (and probably never will) read publications such as Stone Fox, The One and Only Ivan, Bridge to Terabithia, and Shiloh, and most likely shall continue to avoid them all at costs. (We were assigned The Giver one semester, and I literally threw it at the wall after 50 pages.)

But, (thankfully), there are still plenty of books that I can read to my own kids, that I think are great for all kinds of children, and that I’d definitely recommend as a parent and as a teacher.

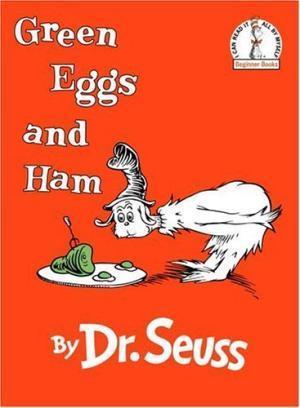

Exhibit A: Dr. Seuss.

Anyone who says Dr. Seuss is “outdated” because “nonsensical wording is harmful to the development of our children’s brains” has obviously never interacted with an actual human child. They do nonsense things on a regular basis. They use words that do not exist in mortal tongues. They take pride in this behavior. So, quite frankly, we should build more statues and grant more awards to the man who figured out just how to speak their language, and then was kind enough to write it down so that parents could get in on the gig.

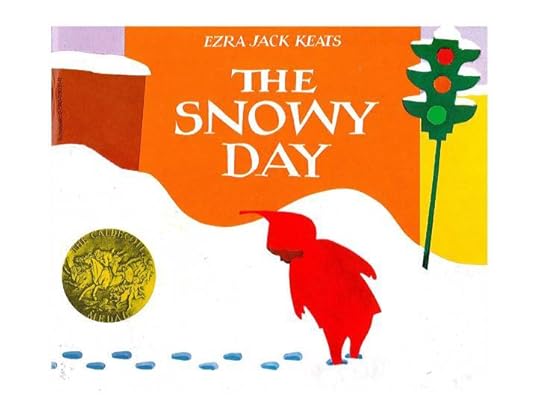

Exhibit B: Diversity stories that focus much more on the story than “look, it has diversity”.

In the mid 20th century, a whole lot of picture books were about Johnny and Jane, riding their bikes in the field while Daddy went to his office job and Mommy baked cupcakes all day. Simply not relatable to a ton of the American population after about 1900. So, when picture books including all the ethnic groups and city life and single parents who were janitors started becoming a real thing, many people were happy about it, as they should be. Books that simply represent different cultures or societies as a natural part of the story (like the works of Ezra Jack Keats, or the Knufflebunny tales) are very valuable to increasing literacy and growing tolerance.

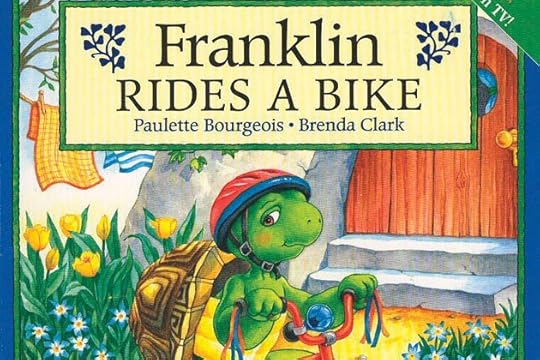

Exhibit C: Animals behaving like people to teach kids everyday lessons.

One of my personal favorites for White Fang was Franklin. This little turtle was just an average guy, trying to get through very normal mishaps like a misunderstanding with a friend, not wanting to follow a rule, or being nervous about starting something new. Now he’s considered a classic, along with the creations of Sandra Boynton and Suzanne Bloom, all still very relatable choices for internet-era munchkins. The fantastic thing about using animals instead of people is that kids from all sorts of backgrounds connect to the feelings and situations, without there being an obvious ethnic/cultural gap.

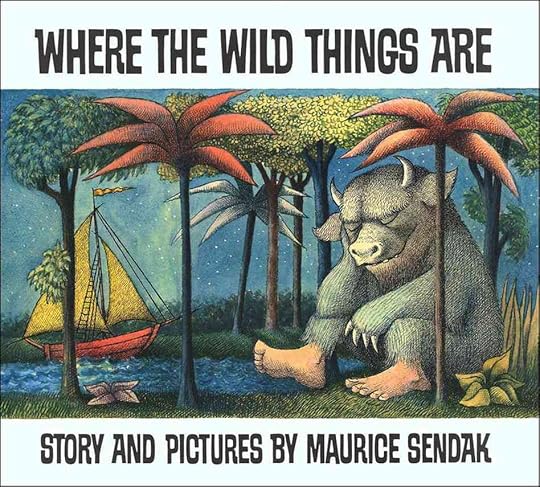

Exhibit D: Books that use metaphors or symbolism discreetly.

Little kids don’t like allegory. They don’t understand it, it doesn’t have meaning, and it often leads to MG/YA students resenting whole genres (or even reading itself), for adults trying to force it on them. That’s why a story like Where the Wild Things Are — which targets Max’s bad behavior and his desire for control, the consequences of his breaking the rules and his plan to escape, his eventual acceptance of the situation, and his mother’s forgiveness of the mischief, all within the idea that he may or may not have visited a remote island of monsters — is brilliant.

(And if you weren’t aware of the deeper meanings to that story, find a copy and re-read it for yourself.)

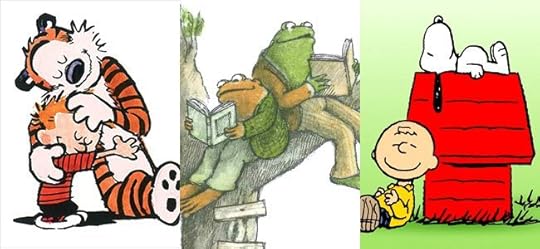

Exhibit E: Characters that have ongoing appeal, and therefore, significance to many generations.

Just because Winnie the Pooh and friends first appeared nigh on a hundred years ago doesn’t mean kids today don’t understand the silly ol’ bear. The same goes for so many other “dated” tales, especially where the focus was always much more on things like friendship, problem solving, and considering the feelings of others, than the time period the original author wrote in. After all, there are some things we hope to teach every generation, regardless of whether they’re living in the 1980s or the 2020s.

[image error]

Daley Downing's Blog

- Daley Downing's profile

- 36 followers