Buyers Guide || Cameras for backpacking: Phones, point-and-shoots, compacts & interchangeable-lens

Photography is often more about being at the right place at the right time. But a good camera helps, too. Sunset on the St. Vrain Glaciers, Indian Peaks Wilderness.

Last week I spent many more hours researching and deliberating about the purchase of a new camera than any non-obsessive person ever would. While they’re still fresh and relevant, I’ll share some backpacking-specific buying and product insights that I wish I had found elsewhere.

Personal context

I primarily use my camera for backpacking, followed by travel, social and family events, and website content. Photography is mostly a secondary concern: I like to have high quality recordings of my trips, but I’m not willing to dedicate serious time (or pack weight) to it.

For over a decade I used Canon Powershot S-series cameras — the S80, S90, and for the past four years the S100. (For a short while I also used a Panasonic Lumix LX-3, but it incurred irreparable water damage during a wet snowstorm in the Wrangells.) The S-models were lightweight, slipped easily into a hipbelt or pants pocket, and offered impressive image quality for their size, weight, and cost.

Alas, it was time to upgrade — in the six years since my S100 was released, technology has leapt ahead. Plus, the lens cover on my S100 was no longer working properly, and the screen got cracked last summer when I slipped on some slimy granite.

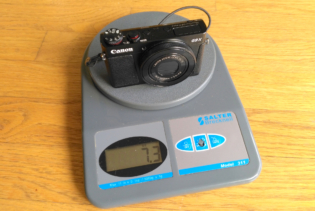

Old and new: my extensively used Canon S100, right; and its replacement, the Canon G9X II. Size and weight are similar, but the image quality on the G9X is far better.

Form factor

When shopping for a backpacking camera, first:

Assess the importance of photography/videography to you, both the art and the results; and,

Identify the features that you must have.

These two considerations will help get you to the appropriate form factor.

Smartphones

Two years ago Apple launched its “Shot on iPhone 6” campaign, featuring photographs on billboards and in glossy magazines shot with its then-flagship model. Look no further for proof that smartphones are legitimate cameras — and, for many people, the only camera they need.

I’m less convinced that they make good backpacking cameras, but they do have a few advantages:

Acceptable image quality for most applications;

Fast and easy sharing of photos and video on social platforms;

Lightweight, because you probably will carry it anyway:

It’s generally unwise to leave it in the car at a trailhead; and,

In the field it doubles as a handheld GPS, keyboard for an inReach satellite messenger, entertainment device, and (where cell service is available) telephone; and,

Inexpensive, because you probably already own it.

For infrequent shooters and for those who want to regularly update their social media platforms, the smartphone is probably the best option. Do yourself a favor though: use a grippy case that is resistant to shock and the elements, and on longer trips bring a Anker PowerCore 10000 charger or similar.

Crater Lake and the Lone Eagle Cirque, taken with a Nexus 5 smartphone

Nearly the same photo, taken with a 6-year-old point-and-shoot. Notice how this photo has more detail in both the shadows and in the sunny areas. Closer inspection shows better resolution of small features like clouds and trees, too.

Point-and-shoots

Smartphones have eviscerated the low-end point-and-shoot (P&S) market, typified by the 5.2-oz Canon Elph 360. But, at least for backpacking, there is still a case to be made for using one, instead of a phone:

Physical dials that can be operated in the rain and with cold or gloved hands;

Better shooting ergonomics;

Longer-lasting battery;

Optical zoom lens, for higher resolution of zoomed images & video;

Faster start-up and focus;

Less screen glare in bright sunlight;

Extreme resistance to water and drops (possibly), such as with the Olympics TG-4 Tough;

Better low-light performance (probably);

Reasonably priced; and;

Reduces exposure of your expensive smartphone to precipitation, sand, tree sap, and drops.

P&S models are suitable for moderate users who want a better camera and shooting experience than offered by a smartphone, but who are unwilling or unable to spend more money on the next category up, enthusiast compacts.

Enthusiast compacts

The smartphone may have killed off the point-and-shoot, but it also created the enthusiast compact category. To remain relevant camera manufacturers were forced to develop P&S-sized cameras with image quality and a shooting experience that was head-and-shoulders above any smartphone.

Enthusiast compacts are ideal for backpackers like me: frequent shooters who value image quality and manual control, but who want the weight and packability of a P&S.

Sony was the first to squeeze an oversized sensor and fast lens into a compact body. It released the groundbreaking RX100 in 2012, and has followed up with four subsequent models. Unfortunately, each successive generation seems to get heavier, larger, and more expensive. The latest, the Sony RX100 V, retails for an astounding $1000 and is almost 25 percent heavier than the original. As new models have been introduced, the older models have remained available at lower price points.

Canon and Panasonic have entered the category as well. Of note, Canon holds the entry-level price point with the PowerShot G9 X, which now sells for $400 and which weighs 7.3 oz. It’s a S-series camera on steroids, and even weighs 0.3 oz less than the S120, which was the last of the S-series.

Personally, I chose the second-generation Canon G9 X II, which shares the exact same body and lens but which has better low light performance, more rapid burst shooting, and faster start-up and focus thanks to a next-generation processor, the same used in the Sony RX100 III (which costs $220 more, $480 versus $700, although some might consider the electronic view finder, swiveling screen, and superior video quality to be worth the premium price).

Interchangeable lenses

If an enthusiast compact is still not enough camera, then you’re looking at an interchangeable-lens model. Enthusiast compacts can compete with this category up to a point; ultimately, however, interchangeable-lens cameras will produce the best images and video, with better image sharpness, less contrast, and no color fringing.

Interchangeable-lens cameras can be further divided into:

Mirrorless, like the Sony A6500; and,

DSLRs, like the Canon EOS 7D.

Mirrorless models are lighter and smaller than DSLR’s, but both are beyond pocketable or lightweight. They are a commitment, and suitable only for those who prioritize photography as part of their backpacking experience. Alan Dixon is one such backpacker, and on his website has written about his top picks.

The Sony RX100 versus the Sony A6000. The former is small enough for a hipbelt pocket and light enough for a gram weenie. The latter is much more of a commitment, but ultimately can take better photos. Photo credit: Alan Dixon.

In my limited experience carrying mirrorless and DSLR cameras, and watching others try to as well, my biggest complaint is the awkwardness, not the weight. On some trips I’d be willing to carry a kick-ass 1.5-lb camera, but I don’t because the size is not easily portable:

Hands get tired and are needed for other things;

If slung over a shoulder, it doesn’t stay put;

Chest mounts get in the way on difficult trails or when off-trail; and,

If it’s inside the backpack, it’s never used.

The smoothest system I’ve seen is Alan’s shoulder strap mount, although this would seem limited to lightweight mirrorless cameras with lightweight lenses.

Your turn: What do you use for a backpacker camera, and why?

Disclosure. This website is supported mostly through affiliate marketing, whereby for referral traffic I receive a small commission from select vendors, at no cost to the reader. This post contains affiliate links. Thanks for your support.

The post Buyers Guide || Cameras for backpacking: Phones, point-and-shoots, compacts & interchangeable-lens appeared first on Andrew Skurka.