Let’s end the first hundred days

The 30 April marks the one hundredth day of the Trump presidency. The media will be deluged with assessments about what Donald Trump accomplished — or didn’t — during his first one hundred days. But this an arbitrary, and even damaging, way to think about presidential performance.

“The first hundred days” is embedded in American political culture. During the presidential race, Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton made big promises about what they would accomplish in their first hundred days in office. As president, Trump has kept score of his accomplishments in that period. The media has kept a steady watch on his triumphs and setbacks as well. MSNBC has used a “first 100 days” chyron on its broadcasts for the last several weeks.

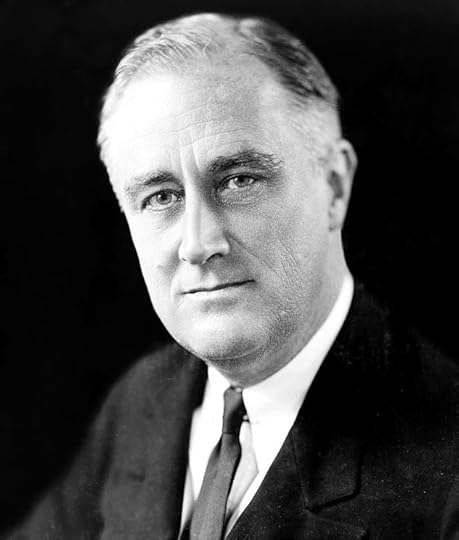

Two people are to blame for this marker. The first is Franklin Delano Roosevelt. At his inauguration in March 1933, FDR promised bold action to address the “national emergency” of the Great Depression. FDR didn’t say anything about 100 days. By the end of June, however, his allies were boasting about the administration’s accomplishments. Senator Clarence Dill bragged that “these first 100 days of Roosevelt will be known in history as the greatest peaceful revolution in the annals of organized government.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fair Use via the US Library of Congress.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Fair Use via the US Library of Congress.Still, that wasn’t enough to fix “100 days” in America’s political consciousness. For the next quarter century, it didn’t matter much at all. The Truman administration tried to recreate the magic of 1933 without success. Most people recognized that FDR had been given unusual leeway because he faced an extraordinary crisis. Dwight Eisenhower also faced a few “100 days” appraisals in 1953. But pundits refused to get on the bandwagon. “It’s just a relic of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration,” one wrote. “Actually 100 days is too little time in which to size up any administration.”

The 100-day benchmark really gained traction after 1959, when the Harvard historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. published the second volume of his history of the FDR years. The book converted the first months of FDR’s presidency into a myth. Schlesinger called that period “The Hundred Days” — a time of “intense drama and prodigious legislation.” Schlesinger was a key advisor to John F. Kennedy, whose campaign seized on the idea of recreating FDR’s glory. One veteran of the Kennedy administration recalled the prevailing mood after JFK’s election: “We’ve got to make the first hundred days impressive. We’ve got to do a lot of things fast and differently.”

The political scientist Richard Neustadt, who worked for Truman, tried to warn Kennedy against setting unreasonable expectations. But the effort was futile. The benchmark became fixed in everyday conversation about national politics. “The Hundred Days,” one columnist explained in 1961, “are any President’s grand opportunity to create the atmosphere for himself to establish leadership.” Over the next half-century, presidents wrestled with the 100-day standard. If they did not adopt it themselves, others imposed it on them.

But there are good reasons to be skeptical about the 100-day benchmark. FDR faced truly extraordinary conditions. He won the 1932 election in a landslide, while Democrats won solid majorities in both house of Congress. People were desperate for strong leadership. Some even played with the idea of dictatorship. Few disagreed when Roosevelt compared the economic emergency to a state of war. Under those circumstances, people weren’t fussy about whether the content of federal policies was exactly right. They were happy to see the government do anything. “The country demands bold experimentation,” Roosevelt said during the campaign. “Above all, try something.”

No president after FDR has faced similar conditions. As a matter of practical politics, no later president has enjoyed such an immense political mandate, or led a nation that was so hungry for strong leadership. And as a matter of policy, no later president has faced such a simple playing field. FDR wasn’t worried about overhauling established policies and bureaucracies. He had a blank slate, and anything he might do seemed better than doing nothing at all.

The world is different today. Both politics and policies are more complex. And yet we persist in revering the myth of The Hundred Days. This isn’t just unfortunate: it’s dangerous. It leads presidents and legislators into debacles like the attempts to repeal Obamacare. President Trump should have allowed more time for an overhaul of the complicated healthcare law. But Trump had already added this to his extensive list of 100-day promises. The rush — and eventual failure — has only aggravated the perception that Washington is dysfunctional.

In fact, we ought to be especially wary about the 100-day benchmark today. In an era of political polarization, rushing to action is a bad idea. Not only is it unlikely to be successful, it also stokes anxiety within the large bloc of voters who happen to be on the losing side of an election. It heightens fear that everything they care about is in immediate danger.

In 1787, the drafters of the Constitution debated how long the President’s term should be. They settled on four years for good reason. As Alexander Hamilton explained, presidents need time to make and execute well-crafted plans. The 100-day benchmark undermines that logic. Perhaps it made sense at one special moment in history, when rapid action was key to national recovery. Today, the 100-day marker doesn’t bring the country together. It drives the nation apart.

Featured image credit: 1933 Franklin D. Roosevelt’s First Inauguration by US Capitol. Fair use via US government works .

The post Let’s end the first hundred days appeared first on OUPblog.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers