Their Hours Upon the Stage: Performing ‘Hamlet’ Around the World

This content was originally published by STEPHEN GREENBLATT on 21 April 2017 | 12:00 pm.

Source link

Photo

Naeem Hayat and Tom Lawrence as Hamlet and Laertes at the Odeon Amphitheatre in Amman, Jordan.

Credit

Sarah Lee

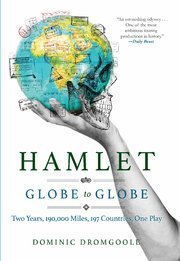

HAMLET GLOBE TO GLOBE

Two Years, 190,000 Miles, 197 Countries, One Play

By Dominic Dromgoole

Illustrated. 390 pp. Grove Press. $27.

It began, we are told, as a whim lubricated by strong drink. In 2012 the management of Shakespeare’s Globe — the splendid replica of the Elizabethan open-air playhouse, built on the bankside of the Thames in London — was considering possible eye-catching new initiatives. In the midst of the merry collective buzz, the theater’s artistic director, Dominic Dromgoole, impulsively said, “Let’s take ‘Hamlet’ to every country in the world.” No doubt even crazier cultural ideas have been proposed, but this one is crazy enough to rank near the top of anyone’s list. Yet it came to pass. An intrepid company of 12 actors and four stage managers, backed up by a London-based staff that undertook the formidable task of organizing the venues, obtaining the visas and booking the frenetic travel, set out in April 2014, the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth. They did not quite succeed in bringing the tragedy to every country — North Korea, Syria and a small handful of others eluded them — but they came pretty close. One hundred ninety countries and a series of refugee camps later, the tour reached its end in April 2016, the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

While helping to run the busy theater in London, Dromgoole managed to venture off and see for himself some 20 iterations of the production he had co-directed and launched. “Hamlet Globe to Globe” is a compulsively readable, intensely personal chronicle of performances in places as various as Djibouti and Gdansk, Taipei and Bogotá. The book is in large part a tribute to the perils and pleasures of touring. The Globe troupe had to possess incredible stamina. Keeping up an exhausting pace for months on end — Lesotho on the 1st of April, Swaziland on the 3rd, Mozambique on the 5th, Malawi on the 8th, Zimbabwe on the 10th, Zambia on the 12th, and on and on — they would fly in, hastily assemble their set, unpack their props and costumes, shake hands with officials, give interviews to the local press, and mount the stage for two and a half hours of ghostly haunting, brooding soliloquies, madcap humor, impulsive stabbing, feigned and real madness, graveside grappling, swordplay and the final orgy of murder. Then after a quick job of disassembling and packing, they were off to the next country. When one or two of the company became ill, as occasionally happened, the group had rapidly to reassign the roles; when almost all of them succumbed at the same moment, as befell them after an imprudent dinner in Mexico City, they had to make do with improvised narration and zanily curtailed scenes.

Dromgoole explains that he set the troupe up in the full expectation that not everyone would last the full two years. Hence his insistence that all the actors learn multiple parts so that they could switch around at a moment’s notice. As it happened, the same 16 people miraculously made it through the whole tour. Perhaps changing roles from time to time helped them build the collective sense of trust that sustained them. Perhaps too, as Dromgoole suggests, they drew upon “the gentle support of each line of verse,” so that even in the most trying of circumstances Shakespeare’s iambic pentameters “kept them upright and somehow kept them moving forward, into the story and towards the audience.”

Photo

Touring is particularly resonant for “Hamlet,” since Shakespeare’s tragedy features a traveling company of players who arrive in Elsinore and are greeted warmly by the prince. Hamlet makes clear that he has a lively interest in the theater, but that interest is not purely aesthetic. He asks the players to stage a court performance of an old play, “The Murder of Gonzago,” to which he says he has added a few lines. His secret intention is to see if the play triggers in his uncle an involuntary display of guilt, thereby confirming the charge of murder made by his father’s ghost. In the event, the uncle does arise in a rage and brings the performance to a halt, but like almost everything else in the tragedy, the signs are ambiguous. The poor players, in any case, could have no way to grasp why their show provoked such a response. A wonderful production I saw years ago showed them hastily packing up their bags in fear and rushing away.

Continue reading the main story

The Globe company, of course, was always packing up and rushing away to the next venue. They did not deliberately set out to provoke moral crises and confessions of murder, even in the most benighted of the countries they visited, but they certainly hoped that the tragedy’s celebrated interrogation of social and psychological ills — “Th’oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely, / The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay, / The insolence of office” — would have some beneficial influence. Tragedy, Shakespeare’s contemporary Sir Philip Sidney wrote, “openeth the greatest wounds, and showeth forth the ulcers that are covered with tissue”; it “maketh kings fear to be tyrants.” “Hamlet” seems particularly suited to this task because of what Dromgoole calls its “protean nature.” It seems to work equally effectively in the urban heart of the most advanced industrial country and on the shores of the remotest Pacific island.

Continue reading the main story

The post Their Hours Upon the Stage: Performing ‘Hamlet’ Around the World appeared first on Art of Conversation.