Illuminating the Beats From Their Shadow

This content was originally published by DWIGHT GARNER on 6 April 2017 | 9:21 pm.

Source link

He was broke, hungry, distraught. She bought him a plate of frankfurters. He followed her back to her small apartment. A door had swung open in her life.

Thus began an off-and-on relationship that lasted nearly two years, years that witnessed the publication of “On the Road” and life-altering fame — not only Kerouac’s but also that of many of his closest friends, other Beat Generation writers.

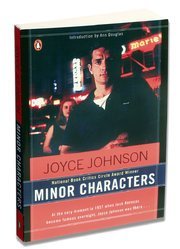

Johnson captures this period with deep clarity and moving insight in her memoir “Minor Characters” (1983). It’s hardly an unknown book. It won a National Book Critics Circle Award, and it has remained in print since it was issued.

Photo

Joyce Johnson in 2009. More than a memoir of her time with the Beats, “Minor Characters” is a riveting portrait of an era.

Credit

Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein bild, via Getty Images

I’m including it in this series of columns about neglected American books because I so rarely hear it mentioned, and because I continue to think it is hideously undervalued and under-read. “Minor Characters” is, in its quiet but deliberate way, among the great American literary memoirs of the past century.

Continue reading the main story

Johnson’s book takes its title from her realization that — as was so common in every sphere of cultural life in the 1950s and beyond — the Beats were a boy gang. She would always be, at best, on its periphery. Her memoir braids and unbraids, at length, the meanings of this fact.

Continue reading the main story

She recalls how the women at the San Remo and other bars, hangouts for writers and artists, “are all beautiful and have such remarkable cool that they never, never say a word; they are presences merely.” Johnson and her friends wanted to be among the yakkers, the all-night arguers.

Continue reading the main story

“Minor Characters” is not just about the Beats. It’s about many different subjects that bleed together. In part it’s a portrait of Johnson’s cloistered middle-class childhood on the Upper West Side. Her parents wanted her to be a composer.

She longed for escape and began sneaking down to Washington Square Park to be among the musicians and poets. She was round-faced, well-dressed, virginal. She’d never tasted coffee. It was “my curse,” she writes, that “my outside doesn’t reflect my inside, so no one knows who I really am.”

Her book is a riveting portrait of an era. It contains a description of a back-room abortion that’s as harrowing and strange as any I’ve read. Johnson had the abortion because she didn’t love the boy and wasn’t ready for a child.

Continue reading the main story

“Sometimes you went to bed with people almost by mistake, at the end of late, shapeless nights when you’d stayed up so long it almost didn’t matter,” she writes. “The thing was, not to go home.”

Photo

Credit

Alessandra Montalto/The New York Times

“Minor Characters” is a glowing introduction to the Beats. There are shrewd portraits of not just Kerouac and Ginsberg but people like Robert Frank and Hettie Jones.

Continue reading the main story

Johnson has a knack for summing up a character in a blazing line or two. Here’s how she describes the Beat-era figure Lucien Carr, for example, at the moment he first met Kerouac: “This rich, dangerous St. Louis boy with the wicked mouth who’s already been kicked out of Bowdoin and the University of Chicago, who’s amassed a whole dissipated history by the age of 19.”

Best of all, perhaps, this book charts Johnson’s own career as a budding writer. She worked in publishing when she was young; she was secretary to John Farrar of Farrar, Straus and Cudahy (later Farrar, Straus & Giroux). He wanted to promote her; she left instead to visit Kerouac in Mexico and write. She published her first novel, “Come and Join the Dance,” when she was 26.

Continue reading the main story

By then, she and Kerouac had separated for good. There was a final scene on a sidewalk. “You’re nothing but a big bag of wind!” she shouted at him. Kerouac, constitutionally unable to remain with one woman, shouted back, “Unrequited love’s a bore!”

Continue reading the main story

Johnson looks back on the young woman she was, while with Kerouac, and realizes she was “not in mourning for her life. How could she have been, with her seat at the table in the exact center of the universe, that midnight place where so much is converging, the only place in America that’s alive?”

I remember tracking down a first edition of “Minor Characters” — this was harder in the late 1980s than it is today — to give to my college girlfriend as a graduation present. She looked at its title, wrinkled her brow and asked, “Why this book?” Why a book, in other words, about women who are minor characters?

I fumbled my answer. I knew only that I loved the book and wanted to share it. What I wish I had said is this: “Minor Characters” is better than all but a handful of books the boy-Beats themselves wrote. It’s a book about a so-called minor character who, in the process of writing her life, became a major one.

Continue reading the main story

The post Illuminating the Beats From Their Shadow appeared first on Art of Conversation.