W.T. BALLARD—INTERVIEWED BY STEPHEN MERTZ

Stephen Mertz and I have been writing contemporaries and friends for longer than either of us would care to mention. We were recently able to spend some time together during an epic used bookstore crawl in Arizona. We talked non-stop smack about books, editors, publishers, and dead authors. The below interview by Steve of pulp wordslinger Todhunter Ballard originally printed in the Armchair Detective #197, Winter, 1979…

Stephen Mertz and I have been writing contemporaries and friends for longer than either of us would care to mention. We were recently able to spend some time together during an epic used bookstore crawl in Arizona. We talked non-stop smack about books, editors, publishers, and dead authors. The below interview by Steve of pulp wordslinger Todhunter Ballard originally printed in the Armchair Detective #197, Winter, 1979…

********W.T. BALLARD—INTERVIEWED BY STEPHEN MERTZ

I first made contact with W. T. Ballard early in 1976. I was researching an article on the detective pulp magazines for which Ballard wrote extensively during the thirties and forties, and his response to my questions was generous, informative and entertaining. Since I'd been a fan and collector of his work for some years, I felt that the next logical step should be a piece dedicated to the man himself. This interview is the result.

Willis Todhunter Ballard was born in Cleveland in 1903. His career as a professional writer began in 1927 and since then he has produced 95 novels, about fifty movie and TV scripts and more than one thousand short stories and novelettes which have appeared in the pulps as well as such "slicks" as The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, This Week and McCall's. His most recent work has been primarily in the western field. He is past vice-president of the Western Writers of America and his novel, Gold in California, won that organization's award as Best Historical Novel for 1965. His latest book is Sheriff of Tombstone (Double day, 1977) and he's presently at work on a new one, also a western.

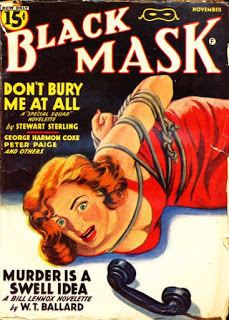

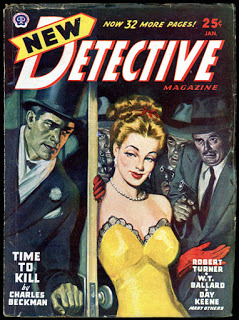

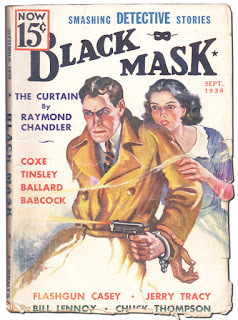

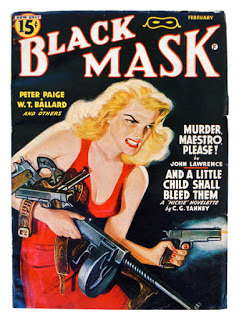

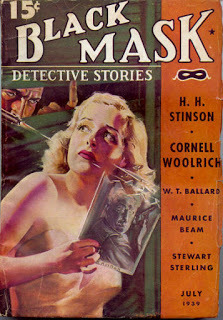

Willis Todhunter Ballard was born in Cleveland in 1903. His career as a professional writer began in 1927 and since then he has produced 95 novels, about fifty movie and TV scripts and more than one thousand short stories and novelettes which have appeared in the pulps as well as such "slicks" as The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, This Week and McCall's. His most recent work has been primarily in the western field. He is past vice-president of the Western Writers of America and his novel, Gold in California, won that organization's award as Best Historical Novel for 1965. His latest book is Sheriff of Tombstone (Double day, 1977) and he's presently at work on a new one, also a western.  His importance to the mystery field is that he was one of the original contributors to Black Mask, that famous detective pulp which, during the thirties under the editorship of Joe Shaw, pioneered the then-revolutionary American hard-boiled detective form.

His importance to the mystery field is that he was one of the original contributors to Black Mask, that famous detective pulp which, during the thirties under the editorship of Joe Shaw, pioneered the then-revolutionary American hard-boiled detective form. Ballard, along with Chandler, Hammett and Erle Stanley Gardner, was one of that magazine's most popular contributors among contemporary readers. His series starring Bill Lennox, troubleshooter for General Consolidated Studios, set the tone and laid the ground rules for countless Hollywood-milieu mysteries to follow.

"My life is not particularly interesting," Ballard wrote me when agreeing to this interview. "As Dash Hammett used to say, there are two types of people in the world. Those who make news and those who write about them."

What follows is proof positive that W.T. Ballard is as self-effacing as he is important to the development of the American detective story.********First, the traditional question: How did you come to be a professional writer?

As a child when I was asked what I wanted to do I said I would live in a library and write books. At age twelve I sold my first offering to Hunter Trader Trapper, the saga of a twelve-year-old on vacation at a Canadian trout stream with my family. I received in return for it ten copies of the issue in which the masterpiece appeared. However, the progress to writer was hit or miss for a long time. My father owned an electrical engineering office. They also published a magazine electrically oriented, on which I worked. When I got out of college I was taken into the office to be taught the business, whether or not I liked it. They sat me at a drawing board. I was not a particularly good draftsman. A whole set of handbooks told me precisely what generators were required in any given situation. Thoroughly bored, I looked for another outlet.

As a child when I was asked what I wanted to do I said I would live in a library and write books. At age twelve I sold my first offering to Hunter Trader Trapper, the saga of a twelve-year-old on vacation at a Canadian trout stream with my family. I received in return for it ten copies of the issue in which the masterpiece appeared. However, the progress to writer was hit or miss for a long time. My father owned an electrical engineering office. They also published a magazine electrically oriented, on which I worked. When I got out of college I was taken into the office to be taught the business, whether or not I liked it. They sat me at a drawing board. I was not a particularly good draftsman. A whole set of handbooks told me precisely what generators were required in any given situation. Thoroughly bored, I looked for another outlet. Through a friend I found a job with a small group of local newspapers, the Brush-Moore chain in the Midwest. It was a constant hassle. In eight months I was fired at least eight times. Besides arguments with the printers I had them with the old battle-axe who ran the front office. She had been secretary to the Brush boys' father and considered that she owned the company more than the boys did. It became a routine. She would call me in and fire me, but before I could clear out my desk one or other brother would show up from Europe and rehire me. This went on until one time no one appeared and I stayed fired.

About that time the stock market crashed in '29 and we were sunk in the Depression. Dad was forced to close his business and I was out of that job too. I couldn't find anything in the East and decided it was a good time to go to California where at least it was warm for sleeping on park benches. I got there on Armistice Day with twenty-six dollars. On the way west I broke out with an infection in the lymph glands and spent three weeks in an Albuquerque, New Mexico, hospital, which cost me most of what money I had.

About that time the stock market crashed in '29 and we were sunk in the Depression. Dad was forced to close his business and I was out of that job too. I couldn't find anything in the East and decided it was a good time to go to California where at least it was warm for sleeping on park benches. I got there on Armistice Day with twenty-six dollars. On the way west I broke out with an infection in the lymph glands and spent three weeks in an Albuquerque, New Mexico, hospital, which cost me most of what money I had. I walked down Hollywood Boulevard like any tourist. There was a big parade in downtown L.A. and the Hollywood streets were all but empty, most businesses closed. But a cigar store newsstand was opened and I stopped to gawk in the window. I had been writing and submitting copy to New York without much success, but there before me was a copy of Detective Dragnet featuring a story I had written months earlier. I didn't take much notice. I had been paid long before and the money was spent. I wandered on and was crossing Cherokee Street when a voice called, "Tod. Tod Ballard..." I looked down the side street and, coming toward me, I saw Major Harry Warner.

I’d known Warner in Cleveland where his family was making movie trailers for Community Chest and other local organizations. They came from Youngstown where the old man was a tailor, a really sweet guy, and when I was with the Brush outfit I had handled some publicity for them as a favor. That was my only connection with them. The Major wanted to know what I was doing in Hollywood, a question I was beginning to ask myself. I hated to admit that I was out of a job and nearly broke, that I had no real hope of finding work in a strange town. Then I remembered the magazine in the window. I lied gracefully. "I'm freelancing, working for magazines...here. I'll show you..." I led him back to the cigar store, went in, bought the Detective Dragnet, took it out and presented it to him.

I’d known Warner in Cleveland where his family was making movie trailers for Community Chest and other local organizations. They came from Youngstown where the old man was a tailor, a really sweet guy, and when I was with the Brush outfit I had handled some publicity for them as a favor. That was my only connection with them. The Major wanted to know what I was doing in Hollywood, a question I was beginning to ask myself. I hated to admit that I was out of a job and nearly broke, that I had no real hope of finding work in a strange town. Then I remembered the magazine in the window. I lied gracefully. "I'm freelancing, working for magazines...here. I'll show you..." I led him back to the cigar store, went in, bought the Detective Dragnet, took it out and presented it to him. Why the Major was impressed by a dime pulp I'll never know, but he was. The meeting culminated in his offering me a job writing for the studio at seventy-five bucks a week. A bonanza at the time. He and his brothers had just taken over First National Studios from Commodore (Commy) Blackton, who had gone broke in New York real estate. I lasted with Warners for eight months—learning a lot about screenwriting from a couple of wise old-timers—before I forgot to watch my back. I made a derogatory crack about Jack Warner, turned my head to find him at my shoulder, and the pink ticket beat me back to my office.

From there, I went to Columbia, an eye-opening experience. Sam Cohan, who owned the studio with his brother, had worked out a crummy deal. A Hungarian, he had brought eight of his relatives over to this country, with no intention of personally supporting them. Instead, he set up an ingenious company, gave each relative a share in the stock, and the titular title of producer to make pictures as independents. Then he would buy these productions and divide any profit with each contributing relative.

The snag was the first man he made a producer spent more money on his pictures than he could hope to realize from their sale. I was hired to recoup the losses, to bring in new films for a very low budget of ten thousand dollars each. We were in the bottom of the Depression, but the job still wasn't easy. I had to write the script, direct, produce the picture and even move the sets and scenery, as it was before the days of powerful unions. The camera was housed in a heavy concrete booth mounted on piano casters, the sound table in the same booth. When you needed to move the apparatus, everyone—grips, juicers, stagehands, actors (including stars)—put their shoulders to the booth and wrestled it into the new position.

The snag was the first man he made a producer spent more money on his pictures than he could hope to realize from their sale. I was hired to recoup the losses, to bring in new films for a very low budget of ten thousand dollars each. We were in the bottom of the Depression, but the job still wasn't easy. I had to write the script, direct, produce the picture and even move the sets and scenery, as it was before the days of powerful unions. The camera was housed in a heavy concrete booth mounted on piano casters, the sound table in the same booth. When you needed to move the apparatus, everyone—grips, juicers, stagehands, actors (including stars)—put their shoulders to the booth and wrestled it into the new position. Most of our shooting was done inside. We couldn't afford to go out. The studio was located on Gower Avenue. It was known locally as Gower Gulch because of the preponderance of westerns being made on the lots lining the street and the horde of unemployed actors who gathered outside the gates. When we needed a couple of extras, we opened the window and yelled, then stood out of the way of the stampede.

The job lasted six months and exhausted me. I never cared for studio work. I hated having my scripts torn apart by producers, directors, even the actors who had any clout. I returned to freelancing and made a living, but barely.

How did you come to write for Black Mask?

[image error] I caught The Maltese Falcon on radio. My uncle, with whom I was living, was head of the West Coast Customs Bureau. He would come home at night worn out, collapse in his favorite chair, turn the radio volume all the way up, and go to sleep. I wrote in a small study off the living room and could not escape hearing every sound from the box. I had learned to tune it out of my consciousness, but this night excerpts of dialogue forced themselves through to me. Dialogue the way I had always wanted to write it. I had been trying to please Dorothy Hubbard at Detective Story Magazine, a lady who favored the Mary Roberts Rinehart and Agatha Christie styles and types of material. This was something else again. I went to the living room and listened. What I heard was an ad, a teaser for a movie playing at Warner Brothers' downtown theater. I caught a streetcar down and saw the show.

This was not the later Bogie version, but an earlier one starring Ricardo Cortez, who took his stage name from a cigar and acted like it. But I had no interest in the acting. It was the dialogue that enthralled me: Hammett's ear for words sounded the way I thought criminals and detectives should talk. It rang true, the way I wanted mine to do.

The ad gave a credit to Black Mask Magazine, which was the first I had heard of the publication. I left the theater, walked to the corner, bought a copy of the then current issue and read it on the ride back. I felt I was coming home. The story I most remember was written by a boy from Oregon whose family, I later learned, owned the biggest whorehouse in the state. His work sounded authentic.

Bill Lennox was the first hard-boiled series character who worked exclusively against a movie industry setting. Can you tell us something of how you went about creating the series?

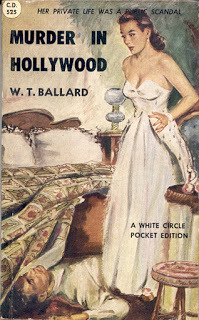

The heroes of most of the Black Mask stories were newspaper crime reporters, which I thought could get monotonous. I scratched my head for an alternative and came up with the idea of a troubleshooter working for a studio. I could use my experience in the movie world for realistic background.

By the time I got back to my uncle's house around midnight I had worked out the basic framework in my mind. A friend, Jim Lawson, was head of the foreign department at Universal. Poor Jim. Every time Junior Laemmle or his sister Rose Mary got into trouble, which was often, Jim had to get out of a warm bed, go to Lincoln Heights jail and bail them out. I couldn't use the name Lawson so I went through the L's in the phone book and came by Lennox. I then needed a name for the head of the studio and wanted something that sounded Jewish, but not obviously so. The phone book yielded me Spurk; there was only one of those. Much later I learned Spurk was a lady and not at all Jewish, but she sufficed well for me. Just after midnight I began the first Lennox story. It ran ten thousand words and I finished at five in the morning. At seven-thirty, I took my uncle to work, mailed the manuscript and went home to bed.

By the time I got back to my uncle's house around midnight I had worked out the basic framework in my mind. A friend, Jim Lawson, was head of the foreign department at Universal. Poor Jim. Every time Junior Laemmle or his sister Rose Mary got into trouble, which was often, Jim had to get out of a warm bed, go to Lincoln Heights jail and bail them out. I couldn't use the name Lawson so I went through the L's in the phone book and came by Lennox. I then needed a name for the head of the studio and wanted something that sounded Jewish, but not obviously so. The phone book yielded me Spurk; there was only one of those. Much later I learned Spurk was a lady and not at all Jewish, but she sufficed well for me. Just after midnight I began the first Lennox story. It ran ten thousand words and I finished at five in the morning. At seven-thirty, I took my uncle to work, mailed the manuscript and went home to bed.I had been nickel and diming along, selling an occasional story to Street & Smith, Short Stories, Argosy and so on. I was paid a quarter of a cent to a cent per word, while supporting my parents and an aunt, long since regretting losing the regular salary from Columbia and having quit my job—much as I had hated it. Along with writing, I was looking for another spot, with no luck.

A week after I mailed the story to Black Mask, I received a letter from Joe Shaw. He wanted some changes made, but he sent along a check with the letter, an unheard of generosity and compassion among editors at the time. The major change he asked for was that Bill Lennox not carry a gun as other fictional detectives did, even newspaper reporters. That reporters went armed seemed odd to me, and that a troubleshooter should go naked seemed odder, but it was not a time to argue with an editor. No one with sense argued with Shaw. So, Lennox went without a gun.

Joe Shaw was a strong guiding force where many of his writers were concerned. Did you have any memorable experiences in your relationship with him as an editor?

I loved Shaw better the more I knew him. He was a curious bastard who wanted to write himself and couldn't. He had been president of a highly successful manufacturing company before the First World War. How he got involved in Europe I don't know, but Hoover used him to deliver relief in Belgium after the armistice, then sent him to Greece.

When he came home, he had a manuscript he took to Phil Cody at Warners Publications. He did not sell the story, but he so impressed Cody that he hired Shaw to edit Black Mask on the spot—and he made a fine editor. He could point the way for his writers, contribute much to helping work out their problems with sympathy and understanding, but he could not do the same for himself even though writing was what he most wanted to do.

When he came home, he had a manuscript he took to Phil Cody at Warners Publications. He did not sell the story, but he so impressed Cody that he hired Shaw to edit Black Mask on the spot—and he made a fine editor. He could point the way for his writers, contribute much to helping work out their problems with sympathy and understanding, but he could not do the same for himself even though writing was what he most wanted to do.He wrote two books, both of which Knopf published, not because they were worthy of publication but because Joe wrote them—he was that much appreciated. Both books were bad. I can't remember both titles, but one was Blood on the Curb. At his request, I worked over it with him trying to point out where he had gone off base, but I was not the editor he was. It was an experience, believe me, trying to teach my father how to write.

As I said, I loved him. I sold him more copy than anyone else did, an average of ten stories a year, more than that including characters other than Lennox. Erle Gardner never forgave that I sold one story more to Black Mask than he did during a given period.

Through the years, I have worked with the leading editors of the business. Ray Long, Fanny Ellsworth, Dorothy Hubbard. Erd Brandt. Ken McCormick. Ken Littaur, Ken White, you name them. But none of them offered the help, the assurance, the patience Joe Shaw gave to his writers. It is too bad he has been so overlooked in the history of the craft.

Following my first Black Mask sale, I wrote and sold seven more within three weeks, with Joe buying everything I submitted until Phil Cody told him to quit Lennox for a while. At Joe's suggestion, I began a new series and wrote six Red Drake stories about a race course detective working for the state racing commission. When that wore thin, I switched to several manuscripts on Don Tomasa, a Mexican adventurer working out of Tijuana.

Following my first Black Mask sale, I wrote and sold seven more within three weeks, with Joe buying everything I submitted until Phil Cody told him to quit Lennox for a while. At Joe's suggestion, I began a new series and wrote six Red Drake stories about a race course detective working for the state racing commission. When that wore thin, I switched to several manuscripts on Don Tomasa, a Mexican adventurer working out of Tijuana. Finally Shaw left Black Mask because Warner and Cody decided to cheapen the quality of the content. Fanny Ellsworth took over and I went along. It was a living. But although Fanny was a good editor, it was never the same as with Joe. At the risk of sounding euphoric, there never was a relationship between editor and writer to equal my connection with Cap Shaw.

Your reminiscences of Raymond Chandler are quoted by Frank MacShane, in his biography of Chandler. Did you know Dashiell Hammett?

Yes, and quite well. Until the time he took off with Lillian Hellman. She saw to it he was cut off from his old friends, even Horace McCoy who had been closest to him. McCoy had been a police reporter in El Paso, a genuine tough guy. He and Dash shared an apartment in San Francisco and at one time were virtually broke. Dash was, as many writers are, a compulsive gambler. Joe Shaw finally sent them a check for $250. Their funds were so low they didn't even have a bank account. Dash took the check downstairs to the Chinese restaurant below their rooms to get it cashed. He did not show up for so long McCoy became worried enough to go looking for Hammett. He arrived at the restaurant just in time to see Dash put the last dollar into the claw machine and lose again. The Chinese felt so bad about the loss he unlocked the box and gave Dash a tin cigarette case from it. Thereafter McCoy called the tin piece Hammett's $250 extravagance.

Yes, and quite well. Until the time he took off with Lillian Hellman. She saw to it he was cut off from his old friends, even Horace McCoy who had been closest to him. McCoy had been a police reporter in El Paso, a genuine tough guy. He and Dash shared an apartment in San Francisco and at one time were virtually broke. Dash was, as many writers are, a compulsive gambler. Joe Shaw finally sent them a check for $250. Their funds were so low they didn't even have a bank account. Dash took the check downstairs to the Chinese restaurant below their rooms to get it cashed. He did not show up for so long McCoy became worried enough to go looking for Hammett. He arrived at the restaurant just in time to see Dash put the last dollar into the claw machine and lose again. The Chinese felt so bad about the loss he unlocked the box and gave Dash a tin cigarette case from it. Thereafter McCoy called the tin piece Hammett's $250 extravagance. McCoy wrote They Shoot Horses, Don't They? Jane Fonda made a picture from the story a few years ago. He married some dame who owned a couple of apartment houses at Vine Street and Beverly Boulevard and I lost all track of him. He was a nice guy and a good writer.

McCoy wrote They Shoot Horses, Don't They? Jane Fonda made a picture from the story a few years ago. He married some dame who owned a couple of apartment houses at Vine Street and Beverly Boulevard and I lost all track of him. He was a nice guy and a good writer.Jumping to the other end of the spectrum, did you know Robert Leslie Bellem? He's been called the worst writer of the pulps, yet I've always viewed his Dan Turner, Hollywood Detective series as superb private eye parody.

Yes, I knew Bob I suppose as well as anyone. I can't give you the exact date of our meeting, sometime in the mid-1930's. Soon afterward, we took adjoining offices in an old corner building on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena and worked there until I left for Wright Field during the Second World War, in 1942. During that period, we collaborated a lot on Frank Armer's Super Detective Stories and a number of other mags. Bob was always a good word man, but had trouble with story, which was my field, and he did not work well under pressure. Frequently, he would blow up, come apart and throw the thing in my lap. That was especially true when the longer pieces became popular. His best work was in short material. He was a pugnacious, small man, but easy to collaborate with, never pretentious about his prose, and we edited each other without many battles.

After the end of the war, I returned to the coast and we again got together writing the Death Valley shows for Ronnie Regan, and also stories for a number of magazines. But the magazine market was sinking, TV taking its place. TV was never my forte. It was too restrictive and I had not the patience to go around and around on endless story conferences with producers who didn't know what they wanted, but had to have an oar in. On the other hand, Bob loved it and thrived on it. He was great at talking, but was never what they called a talking writer. He was one of the hardest workers in the field, kept as regular office hours as if he punched a time clock, and stayed at his machine until he finished a predetermined number of pages a day. He had a delightful sense of humor that relied a lot on play on words. I recall one lunch-long game we played using the names of American Indian tribes, using the verbal sounds for different word meaning. An example: Shawnee(ds) more action in this story—Shaw being Cap Shaw. I guess we used up every tribe in the land.

After the end of the war, I returned to the coast and we again got together writing the Death Valley shows for Ronnie Regan, and also stories for a number of magazines. But the magazine market was sinking, TV taking its place. TV was never my forte. It was too restrictive and I had not the patience to go around and around on endless story conferences with producers who didn't know what they wanted, but had to have an oar in. On the other hand, Bob loved it and thrived on it. He was great at talking, but was never what they called a talking writer. He was one of the hardest workers in the field, kept as regular office hours as if he punched a time clock, and stayed at his machine until he finished a predetermined number of pages a day. He had a delightful sense of humor that relied a lot on play on words. I recall one lunch-long game we played using the names of American Indian tribes, using the verbal sounds for different word meaning. An example: Shawnee(ds) more action in this story—Shaw being Cap Shaw. I guess we used up every tribe in the land.  Bob was also a mighty hypochondriac, forever taking pills, medicines, asthma inhalations, anything he could find. He fell into the clutches of the Beverly Hills heart attack doctor, a man who treated many writers and studio people, all of whom he diagnosed as having had or soon to have heart attacks—and some even did. Most did not. However, Bob decided he was a prime candidate and suffered realistically for a couple of years. I never took his complaints seriously until the day he died of a heart attack in the new home he had worried himself to death building.

Bob was also a mighty hypochondriac, forever taking pills, medicines, asthma inhalations, anything he could find. He fell into the clutches of the Beverly Hills heart attack doctor, a man who treated many writers and studio people, all of whom he diagnosed as having had or soon to have heart attacks—and some even did. Most did not. However, Bob decided he was a prime candidate and suffered realistically for a couple of years. I never took his complaints seriously until the day he died of a heart attack in the new home he had worried himself to death building.Incidentally, Bob was not nearly as bad a writer as you make him out. He looked over the markets, chose one he could handle fast and easily, and hewed to the line. And was highly successful in so doing. When he went into television, he was one of the most successful story editors in the trade. He was a generous man, even professionally. Always busy with his and our work, when Cleve F. Adams had a grave illness while in the middle of a detective book manuscript Bob suggested the two of us finish it for him. We did. Cleve was a father figure to the fiction writing group, much loved but a porcupine nevertheless. His comment on reading the finished copy: It's a beautiful...typing job.

For all his popularity with private eye readers during the forties, surprisingly little is known about Adams.

I met Cleve in '31. He and his wife, Vera, had a candy store in Culver City, but he had always wanted to write, and broke in with the old Munsey magazines. With varying success, he continued selling to the pulps until he wrote his first book, Sabotage. It was an instant hit and, on the strength of it, he did seven or eight others. He was good, though hardly in a class with Ray Chandler. He had an exalted regard for his own ability and seldom discussed his work with anyone, including family. I knew him intimately until he died. His son phoned me at four o'clock that morning to tell me Cleve had had a heart attack. He was dead before I could drive over.

He and Glen Wichman and I founded the Fictioneers organization, selecting some twenty men as original members. It was an entirely social group with neither rules nor by-laws. Cleve ran it through the first years as secretary, the only office we had, sending out notices of where and when the next meeting would be held. We paid for cards and postage. I have no idea how many members there were for we kept no records and charged no dues, but I would say the number ran into the hundreds. Any writer, fixed or just passing through, was welcome if he cared to join and at times we had more members than the Authors' League. However, our monthly dinners seldom turned out more than thirty or forty at one gathering. It held together until the war when a lot of the boys went into the services. Although several efforts were made to revive it after the war they were largely unsuccessful because most of us had moved into the slick markets and the book field, and had scattered.

He and Glen Wichman and I founded the Fictioneers organization, selecting some twenty men as original members. It was an entirely social group with neither rules nor by-laws. Cleve ran it through the first years as secretary, the only office we had, sending out notices of where and when the next meeting would be held. We paid for cards and postage. I have no idea how many members there were for we kept no records and charged no dues, but I would say the number ran into the hundreds. Any writer, fixed or just passing through, was welcome if he cared to join and at times we had more members than the Authors' League. However, our monthly dinners seldom turned out more than thirty or forty at one gathering. It held together until the war when a lot of the boys went into the services. Although several efforts were made to revive it after the war they were largely unsuccessful because most of us had moved into the slick markets and the book field, and had scattered. One Black Maskwriter who seems shrouded in obscurity is Raoul Whitfield, who just seemed to vanish at the height of his career.

He died in North Hollywood in the early forties. I don't recall what he died of or what he was doing at the time.

Would you tell us something about the lifestyle of a pulp writer living in L.A. during the thirties and forties?

We all worked hard, played hard, lived modestly, drank—but only a few to excess—gambled some when we had extra cash. Most of our friends were other writers. In the Depression, when any of us got a check, he climbed in his jalopy and made the rounds to see who was in worse straits than he and loaned up to half what he had just received.

More and more interest is being shown these days in the detective pulps and those who wrote for them. Are there any pulp writers who are generally ignored today whom you think deserve recognition?

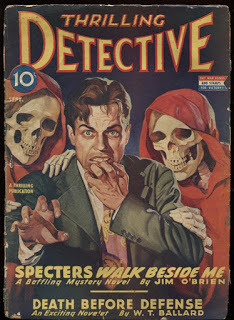

Here are a few from memory. Norbert (Bert) Davis was one of the best with a light style and humor. He killed himself in the odd-forties. John K. (Johnny) Butler who wound up at the studios. Dwight Babcock. Carroll John Daly. Fred Nebel, who was very good.

What was your yearly average word output for the pulps?

My files are at the University of Oregon library, but a shotgun guess would be about or over a million words per year.

Would you tell us something about your work habits both then and now?

I tried to do about ten pages a day after that first Black Mask flush, sometimes more, sometimes less. I tried to work regularly, something every day even if I later threw it away. These days my wife, Phoebe, does the typing since I'm a lousy typist and in so doing edits the copy. I seldom objected to requests for rewrite, but sometimes stood my ground. A late example is a western called Sheriff of Tombstone. Both my agent and my Doubleday editor, Harold Kuebler, held their noses at the first submission and Harold only accepted the altered copy grudgingly. Both let me know in no uncertain terms they considered it a bad work. It has outsold all my more recent books, and is rated second from the top of the list in Western Writers of America's scoring for the last year.

I tried to do about ten pages a day after that first Black Mask flush, sometimes more, sometimes less. I tried to work regularly, something every day even if I later threw it away. These days my wife, Phoebe, does the typing since I'm a lousy typist and in so doing edits the copy. I seldom objected to requests for rewrite, but sometimes stood my ground. A late example is a western called Sheriff of Tombstone. Both my agent and my Doubleday editor, Harold Kuebler, held their noses at the first submission and Harold only accepted the altered copy grudgingly. Both let me know in no uncertain terms they considered it a bad work. It has outsold all my more recent books, and is rated second from the top of the list in Western Writers of America's scoring for the last year. How about the marketing of pulp fiction? I've heard many of the magazines (such as Frank Armer's) were closed to most freelancers. Was this a widespread practice?

How did we market pulp fiction? Like selling any other commodity. No magazine I remember was tightly closed to submissions, although a couple of them were written entirely by one or two men for long stretches. It was largely governed by how lazy the editors were, how much they were willing to read.

[image error] Frank Armer was no worse than others, but his editors were crooked. They were pulling old copy out of the files, slapping a current writer's name on as author, and drawing checks to the new names, cashing them themselves at the bar on the corner. Bob Bellem and I combined to send them to Sing Sing for five years each. We discovered the ploy after I received a notice from the IRS that I had failed to report $35,000 paid me by Armer Publications. Since I had sold them no copy for that year, I checked with Bob. He had sold to them, but he was being charged with not reporting twice what he had been paid. We contacted Frank, then blew the whistle. Armer was an open market but Bob did have the edge by a large margin.

After a highly successful career in the detective magazines under your own name, much of your later work has been pseudonymous. Why the switch?

Frankly, the market for detective, especially from picture studios, became very slim and when I was forced into westerns, I chose to use my middle name—Todhunter—to begin with. But unlike the detective publications, the westerns would not absorb enough copy under a single byline to support me. Especially when I jumped to books. The houses would take only one a year, and a name was tied up solely by one house. Therefore, the shift to a long series of pseudonyms under which I could work for several houses at once. They didn't like it. But the practice became common, and they had to go along or do without sufficient submissions. Later, resales to paperback, as they have reverted to me, have been reissued under only one or two noms.

[image error] The private eye series starring Tony Costaine and Bert McCall, which you did for Gold Medal Books during the fifties and sixties under the pseudonym of Neil MacNeil, was unusual in that it featured two lead protagonists instead of one. I thought it was a good idea, well executed. What happened to the series?

I developed the idea and editor Dick Carrol was enthusiastic. Then he died and Knox Burger took over. Burger was chary of the MacNeil byline because he knew the real Neil MacNeil of Washington. D.C., and my use embarrassed him, although it was an honest family name for me. Knox did his best to kill the series. However, the books were popular and went back into reprint over which Knox had no control. It dragged on until Knox felt it was safe and then did kill both the nom and the series. I had no recourse. Knox left the house soon afterward, but the series was gone. I did two books for Fawcett on the Mafia under my wife's initials, P. D. Ballard. We already had a couple of titles out under P. D. which were highly successful. Then the Mafia market collapsed, the old-time editor, Ralph Deigh, retired, a woman came in as managing editor and my boy who had replaced Knox was fired. Is there a single work you look back on as the highlight of your career?

The single piece of my work that gave me much satisfaction is called Gold in California. It's a good book. It sold over 30,000 copies, which is a huge sale for a western, and I am proud of it. I like also a sort of sequel, same locale and time frame, called The Californian. Do you prefer writing westerns over mysteries? In a way, yes. Most crime fiction is phony. Hammett made it believable because he wrote about people he knew from his experience with the Pinkertons in Baltimore and San Francisco. He avoided the mistake Chandler and his imitators made and make in going psychological, with Little Sisters sucking their thumbs. Westerns are of course exaggerated but there are many classics, and the better recent books such as Elmer Kelton's Time It Never Rained are as near factual and convincing as you can get. When I wrote my first western, I knew practically nothing about the West and its history. Since then I have researched. Learned a lot and had a lot of fun doing It. For nearly fifty years you've remained popular to a most precarious profession while other careers have come and gone. To what do you attribute this staying power? Would you share some of your views on the writing business with us? My views on writing as a business? That it is not much different from any other. You have to keep swinging, rolling with the punches, keep alert and attuned to the changes that take place suddenly or gradually, but always constantly. Copy written in 1930 would not sell today because it is dated and shows it glaringly.

The single piece of my work that gave me much satisfaction is called Gold in California. It's a good book. It sold over 30,000 copies, which is a huge sale for a western, and I am proud of it. I like also a sort of sequel, same locale and time frame, called The Californian. Do you prefer writing westerns over mysteries? In a way, yes. Most crime fiction is phony. Hammett made it believable because he wrote about people he knew from his experience with the Pinkertons in Baltimore and San Francisco. He avoided the mistake Chandler and his imitators made and make in going psychological, with Little Sisters sucking their thumbs. Westerns are of course exaggerated but there are many classics, and the better recent books such as Elmer Kelton's Time It Never Rained are as near factual and convincing as you can get. When I wrote my first western, I knew practically nothing about the West and its history. Since then I have researched. Learned a lot and had a lot of fun doing It. For nearly fifty years you've remained popular to a most precarious profession while other careers have come and gone. To what do you attribute this staying power? Would you share some of your views on the writing business with us? My views on writing as a business? That it is not much different from any other. You have to keep swinging, rolling with the punches, keep alert and attuned to the changes that take place suddenly or gradually, but always constantly. Copy written in 1930 would not sell today because it is dated and shows it glaringly.

In Say Yes to Murder, you describe the library of one character as containing books kept by one who loved reading for the joy that only reading can afford. What do you read for enjoyment? What I read now is very little. I enjoy history, but my eyes don't take kindly to too much strain. I try to keep abreast of the current best sellers to sample the wind and let it go at that. Very few current mysteries, only an occasional John or Ross Macdonald, and neither of those men give me much pleasure. What can you tell us of your current projects? Is there any chance of a new Lennox yarn or has Bill's day come and gone? Currently, I have done nothing since a major operation a year and a half ago. I have been long in regaining strength or enthusiasm. I have just begun another western...not a Bill Lennox who, I fear, has outlived his usefulness. We'll let him rest in his own time frame. W.T. BALLARD A CHECKLISTINCLUDING MISCELLANEOUS READING NOTES

In Say Yes to Murder, you describe the library of one character as containing books kept by one who loved reading for the joy that only reading can afford. What do you read for enjoyment? What I read now is very little. I enjoy history, but my eyes don't take kindly to too much strain. I try to keep abreast of the current best sellers to sample the wind and let it go at that. Very few current mysteries, only an occasional John or Ross Macdonald, and neither of those men give me much pleasure. What can you tell us of your current projects? Is there any chance of a new Lennox yarn or has Bill's day come and gone? Currently, I have done nothing since a major operation a year and a half ago. I have been long in regaining strength or enthusiasm. I have just begun another western...not a Bill Lennox who, I fear, has outlived his usefulness. We'll let him rest in his own time frame. W.T. BALLARD A CHECKLISTINCLUDING MISCELLANEOUS READING NOTES

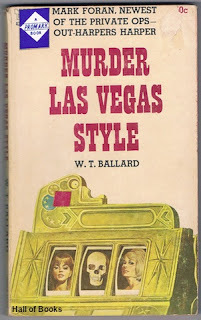

This checklist concerns itself only with Ballard's crime and detective fiction. A complete listing of his novels may be found in the library reference work, Contemporary Authors. The best of Ballard's novels, such as Say Yes to Murder, are highlighted by a crisp, clean prose style, vivid characterization, rapid plot development and a singular humaneness. The Death Brokersis a prime example of his talent for introducing complex, fully dimensioned characters who get under your skin and make you care about them after only one page, involved in a twisty, imaginative story line. Originally packaged to cash in on the Mafia fad, which infested paperback publishing during the early seventies, the book stands on its own as a superb evocation of the all-pervasive fear, treachery and moral decay that is life in the Brotherhood. Murder Las Vegas Styleis neo-Black Mask; a beautifully written private eye novel Raymond Chandler would have enjoyed. This one is highly recommended. Many of Ballard's books are set either completely or partially in Las Vegas, and he always does a convincing job of portraying this fascinating, seldom utilized desert locale with its swinging casinos, its moral ambiguity and the uneasy alliance between gamblers and police. THE BILL LENNOX SERIES

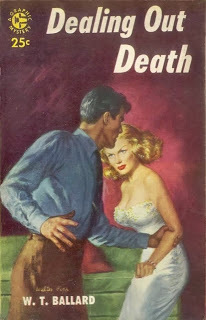

This checklist concerns itself only with Ballard's crime and detective fiction. A complete listing of his novels may be found in the library reference work, Contemporary Authors. The best of Ballard's novels, such as Say Yes to Murder, are highlighted by a crisp, clean prose style, vivid characterization, rapid plot development and a singular humaneness. The Death Brokersis a prime example of his talent for introducing complex, fully dimensioned characters who get under your skin and make you care about them after only one page, involved in a twisty, imaginative story line. Originally packaged to cash in on the Mafia fad, which infested paperback publishing during the early seventies, the book stands on its own as a superb evocation of the all-pervasive fear, treachery and moral decay that is life in the Brotherhood. Murder Las Vegas Styleis neo-Black Mask; a beautifully written private eye novel Raymond Chandler would have enjoyed. This one is highly recommended. Many of Ballard's books are set either completely or partially in Las Vegas, and he always does a convincing job of portraying this fascinating, seldom utilized desert locale with its swinging casinos, its moral ambiguity and the uneasy alliance between gamblers and police. THE BILL LENNOX SERIES•1. Say Yes to Murder. Putnam, 1942. Penguin pb, 1945. Also published as The Demise of a Louse (as by John Shepherd). Belmont pb, 1962.•2. Murder Can't Stop. McKay. 1946. Graphic pb, 1950. •3. Dealing Out Death. McKay, 1948. Graphic pb, 1954. •4. Lights, Camera, Murder (as by John Shepherd). Belmont pb. 1960. THE TONY COSTAINE/BERT MCCALL SERIES •1. Death Takes an Option. Gold Medal pb, 1958. •2. Third on a Seesaw. Gold Medal pb, 1959. •3. Two Guns for Hire. Gold Medal pb, 1959. •4. Hot Dam. Gold Medal pb, 1960. •5. The Death Ride. Gold Medal pb, 1960. •6. Mexican Stay Ride. Gold Medal pb, 1962. •7. The Spy Catchers. Gold Medal pb, 1966. * Written as Neil MacNeil THE LIEUTENANT MAX HUNTER SERIES•1. Pretty Miss Murder. Permabooks pb, 1962. •2. The Seven Sisters. Permabooks pb, 1962. •3. Three for the Money. Permabooks pb, 1963. NON-SERIES BOOKS•1. Murder Picks the Jury (as by Harrison Hunt). Curl, 1947. •2. Walk in Fear. Gold Medal pb, 1952. •3. Murder Las Vegas Style. Tower pb, 1967. Unibooks pb, 1976. •4. Brothers in Blood (as by P. D. Ballard). Gold Medal pb, 1972. •5. The Kremlin File (as by Nick Carter). Award pb, 1973. •6. The Death Brokers (as by P. D. Ballard). Gold Medal pb, 1973.

Stephen Mertz is best known for his mainstream thrillers and novels of suspense. His work covers a wide variety of styles from paranormal dark suspense to historical speculative thrillers and hardboiled noir. His most recent novels include Hank & Muddy, The Korean Intercept, and The Castro Directive. This interview is reprinted by permission of the author—Copyright © 1979 by Stephen Mertz

Stephen Mertz is best known for his mainstream thrillers and novels of suspense. His work covers a wide variety of styles from paranormal dark suspense to historical speculative thrillers and hardboiled noir. His most recent novels include Hank & Muddy, The Korean Intercept, and The Castro Directive. This interview is reprinted by permission of the author—Copyright © 1979 by Stephen Mertz

Published on April 06, 2017 11:46

No comments have been added yet.