The Short Story Interview: Lochlan Bloom

Originally published on The Short Story

Interview by Rupert Dastur

Hi Lochlan, thank you for speaking to us. Could we begin by asking about your development as a writer – when did the craft switch from hobby to profession, and what have been the major landmarks in your development?

Hi! That’s a good question. It’s hard to put my finger on an exact switch. The idea of hobby versus profession is something I struggle to fit to the act of writing.

There seems to be a general assumption that if you are getting paid to do something then it is a profession and if you are not getting paid then it is a hobby but you don’t have to look too far to realise there are plenty of people out there getting paid exorbitant amounts for very little ‘work’ and others producing very serious writing for next to nothing.

I was paid as a writer of non-fiction and journalism before making any money with my fiction writing but that never made one seem like a ‘profession’ and the other a ‘hobby’.

Did you study literature at university? Your debut certainly gives that impression!

Thanks. I studied Physics but I’ve always written and read fiction so my fiction-writing developed relatively organically. Physics and fiction can at times be positioned as polar opposites- the hard-scientific approach versus the wooly and imaginary – but literature and mathematics often approach some of the same sorts of questions about the world. Hopefully The Wave captures some of those.

Why do you think writing is important?

At a very simplistic level I guess it is important as without it we wouldn’t have anything to read. The two processes of reading and writing are obviously linked and we need both if we want to continue that part of who we are.

By ‘that part of who we are’ are you referring to the part of us that is the story-teller or reader?

More in the sense of who we are as a species, culture, etc. Writing has very rapidly become pretty much the primary way we interact. In a relatively short period of time we have replaced a huge amount of our social and business interactions with various forms of text – whether email, online media, Whatsapp, messenger etc…

It’s hard to imagine society without the written word but if we had to somehow go backwards and rely only on spoken/recorded language (and perhaps written mathematics) it seems clear we would all be very different!

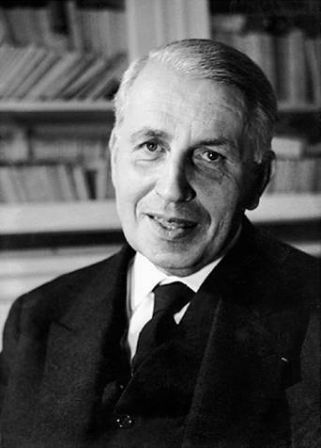

Maurice Blanchot

Obviously when you write a Whatsapp message it is normally with a different intention than writing fiction but the fact that writing is so prevalent does make for a greater continuum of written words. Maurice Blanchot talks about literature beginning at the moment when it becomes a question and I think that some kind of intention to question the world is what drives the most interesting fiction.

Literature is a part of the way we construct the world around us – a great piece of writing can absolutely change your perception – and it is unique in that it’s one of the few art forms that is in a way divorced from the senses. There is an immediacy, a real, instant feeling you get from watching or listening to dance, music, film, sculpture, or artworks on a wall in a gallery. They are all experienced directly via the senses in a way that is not present in reading.

Literature is this weird cryptographic-artform whereby you stare at a page of symbols and ‘something’ appears. If you watch a theatre play or listen to a song in a language that you don’t understand you might not get the full significance but it is never completely obscure. The body language of the actors, the tone of voice, the pitch of the instruments all give an immediate sense of the piece.

If you contrast that with opening a book in a foreign language there is obviously a huge difference. If I open a book of Japanese prose I have literally no idea what its about. There may be a tactile element to the book and you might be able to say something about typography or page layout but I would argue that effect is unlikely to provoke much feeling in the reader.

Other art forms are at one remove from reality – a reflection of reality created by the musician, painter, etc, – but literature is at a double remove – hidden behind this process of deciphering hieroglyphs. I think in a strange way it is this double remove from the real world that gives really good literature its unique lucid quality. Im sure academics have explored this in more depth elsewhere but would be great to read some more on this topic – if any of your readers know any more on this from a neuroscience perspective get in touch!

That’s interesting – I’ve read a lot about reading being a form of interpretation – of all viewing, in fact, as a form of interpretation – of a decoding of signs and symbols through the lens of our own personal psychology and knowledge of the world. Is there a difference between listening to a story and reading it, in so far as levels of remove are concerned?

Yes I think that’s an interesting question. I would say there probably is. There are definitely similarities between reading and listening to a story but the difference with oral storytelling is that it is still tied to our sense of sound (and sight, through body language, if the teller is in front of us).

If we listen to a storyteller in a foreign language we might get some sense of the flow and the emotion even if we don’t understand the words. (although I guess it is possible to mislead the listener and give false emphasis if they don’t understand the words.)

Writing in contrast has none of these sensory clues to ‘flesh out’ the story. If you take this alongside the explosion of writing in modern culture I think it creates some interesting questions about our society and where it is heading. Baudrillard’s concept of sign-order and simulacra and the relationship between reality and symbols for instance is only really possible due to this strange disassociation

from reality that writing possesses.

I also wonder if music also requires a degree of contextual understanding – throughout the world there must be many different variations on what constitutes ‘music’, let alone whether it is good or not.

There is certainly a high degree of contextual understanding involved in appreciating music, as with other art forms, but in each case there is still an immediate sensory element. We can tell for instance that animals react to different forms of music even though they are probably not appreciating it in the same way we do.

You’ve published a number short fiction pieces in a variety of places – one of which we reviewed last year – what attracts you to the short form?

I’m not sure I am attracted to the form so much as some stories somehow end up that length. When writing there is a sense that the length of each scene, plot point, description, etc is already dictated to some extent.

Too short and it does not capture the full effect, too long and it loses the magic.

I might compare it to using a lens to focus an image on a wall. The sharpness of the image depends on the focal length of the lens and the sweet spot depends on the lens itself not the person holding it.

The Open cage by Lochlan Bloom

I was listening to Bill Bryson’s A History of Nearly Everything the other day and there was a passage about sixteenth century French scientists who travelled to South America and generally caused havoc wherever they went – I couldn’t help notice some of the parallels with your chapbook ‘The Open Cage’ and wondered if the story had been inspired by such excursions?

I’ve not read A History of Nearly Everything but certainly ‘The Open Cage’ was influenced by other readings of those early explorers in South America. The conquistadors had this fascinating mix of blood-thirstiness and violence with a deeply held belief in a divine being who exemplified and expounded meekness and sacrifice.

On a related note I recently read César Aira’s short novella An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter which I really enjoyed and brilliantly mixed old-world scientific resolve with surrealistic, almost pagan imagery.

Aside from short prose, you’ve also written for the screen and earlier this year your novel, The Wave, was published. How do these different forms relate to one another, and what are their varying strengths and weaknesses?

For me the form, like the length of a piece of writing, is to some extent determined by what feels natural for the story itself. I might initially try writing something as prose and end up putting it to one side because I feel it’s not working. It might sit there for a while until I get the idea to try writing a piece of dialogue between two of the characters in script format and suddenly it clicks.

With The Wave I knew from the start that I wanted to include certain sections in script format to highlight the distinction between the separate story strands. I wanted to create a novel that constantly brings the reader out of the narrative, where the reader is not only questioning the characters motivations but the text itself. Hopefully that works in the end and it delivers something that a potboiler that you can ‘lose yourself’ in doesn’t but I realize it could well be irritating for a lot of readers too!