Guest post from Nancy Means Wright: An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

Today author Nancy Means Wright is visiting the blog to discuss the historical practice of primogeniture -- in particular as it figured in the lives of her heroine Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary's contemporaries, and their fictional creations. If you read novels with historical British settings, you'll want to understand the concepts of inheritance law explained in this informative post!

Today author Nancy Means Wright is visiting the blog to discuss the historical practice of primogeniture -- in particular as it figured in the lives of her heroine Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary's contemporaries, and their fictional creations. If you read novels with historical British settings, you'll want to understand the concepts of inheritance law explained in this informative post!------

An 18th-century Feminist Takes on an Unfair, Feudal Practice

by Nancy Means Wright

"Property, " Mary Wollstonecraft wrote in her flaming Vindication of the Rights of Man (1790), "should be fluctuating, which would be the case if it were more equally divided amongst all the children of a family. Else it is an everlasting rampart, in consequence of a barbarous feudal institution that enables the elder son to overpower talents and depress virtue."

The "feudal institution" Mary decried in her rebuttal to the reactionary Edmund Burke, was the law of primogeniture. In practice since the Norman conquest, a father's fortune would go directly to the eldest son, and so on down the male line—the objective being to keep estates intact from generation to generation.

"Security of property: Behold in a few words, the definition of English 'liberty,'" was Mary's ironic reply to Burke, who not only upheld the practice but had attacked Mary's mentor, Unitarian Dr. Richard Price who like Mary, was thrilled with the Liberté, Égalité ideals of the French Revolutionaries.

"To this selfish principle (primogeniture)," she declared, "every nobler one is sacrificed!"

The practice was ensured by means of entail, a legal arrangement under which the father had only an allowance and life interest in the estate, which was then entailed to the eldest son. Any sale of the property was prevented by law, resulting in vast estates owned by extravagantly rich families. By the mid-19th century, one quarter of all British land was held by a mere 701 individuals. Primogeniture, they insisted, was the only way to ensure political and economic stability, and so remained on the law books until 1925!

Mary's grandfather had amassed a small fortune as master silk weaver, but her father squandered it in his attempt to become a gentleman farmer. He failed at every move, and drank away much of the inheritance. Mary's autocratic brother Ned didn't inherit enough money to became a man of leisure, like many elder brothers, but he did practice law, and kept for himself the small legacy assigned to his six siblings. So after her mother's death, elder daughter Mary was left with no money, but all the responsibility for her younger brothers and sisters.

At fourteen, Mary's brother Henry was apprenticed to an apothecary-surgeon, and then disappeared from record. But Mary outfitted James for a naval career, and sent Charles off to make his fortune in America (with middling success). She helped her sister Eliza escape an abusive husband; yet unable to remarry, Eliza had to earn her way as governess. Governessing was the fate of the youngest sister, Everina, as well, and for a time, of Mary herself—"a most humilating occupation!" Her whole short life, Mary sent the little money she earned from her writing to prop up her siblings, along with her feckless father.

No wonder then, that early on, as Virginia Woolf put it, life for Mary became "one cry for justice!" And justice was sorely needed, according to philosopher Francis Bacon, who wrote that tempted by money and power, elder sons were likely to become "disobedient, negligent and wasteful."

Like Mary, 18th-century Nelly Weeton valued family ties and responsibilities, even rejecting an offer of marriage to keep house for her elder brother Tom after their father died at sea. But Tom, who as a boy was close to Nelly, married a woman who wanted no part of the sister. He ultimately stole the little legacy their mother left Nelly, and virtually sold her into servitude. A desperate marriage to a tyrant who appropriated her teaching money, and after a separation, denied her entry to their daughter, turned Nelly's life to abject misery. Mary Wollstonecraft's stepsister, Claire Clairmont, had a similar loss when her indifferent lover, poet Lord Byron, an only son, refused all visits to their daughter, who at eight years of age died alone in a convent.

Although loving and supportive, Jane Austen's elder brother Edward took advantage of the system through the practice of surrogate heirship and its device of name changing, aimed at keeping estates whole. Edward was adopted by a distant cousin, Thomas Knight, and gave up the name of Austen for Knight when he inherited. Biographer David Nokes suggested that Jane felt abandoned by her brother, although Jane's only known comment was: "I must learn to make a better K."

Yet the poison of primogeniture is paramount in Austen's novels. In Pride and Prejudice the Bennet estate is entailed to the pompous Mr. Collins, clergyman cousin to Mr. Bennet who had no sons, leaving the silly Mrs. Bennet, who finds the subject of entail "beyond the reach of reason," to scheme up husbands for her five daughters. Should she fail in the event of her husband's death, mother and daughters would have no home or income. In Northanger Abbey, Austen portrays elder brother Frederick as corrupt and cruel, while in Mansfield Park elder Tom is everyone's party boy. Austen questions the validity of primogeniture when she makes younger brother Edmund the good son, although the latter loses the young woman he loves because he isn't rich enough and is destined to become a boring (to her) clergyman. Happily, in the long run, he discovers he's better off without her.

The disparity of riches between elder and younger brothers was huge, often creating a wide rift between siblings. In a lecture on Shakespeare's King Lear, Samuel Coleridge notes "the mournful alienation of brotherly love…in children of the same stock." 19th century Anthony Trollope's novels are full of younger sons pursuing heiresses, or simply seeking a comfortable bachelorhood without an expensive wife—whereas the elder son must marry in order to produce an heir—think Henry the Eighth!

But considering the fates of Henry's wives, it was females who were the true victims. For most females there was little money or opportunity to find a suitable husband; some indigent ladies found a taboo against marrying beneath them and remained spinsters. But the main drawback, as Mary Wollstonecraft makes clear in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, was failure to receive an equal education. A lack of proper schooling, she allowed, often contributed to a pampered indolence in females, and "a false regard for wealth and status over reason and true moral values." In her own life, her mother indulged her first born son, neglecting Mary, though it was Mary, not Ned, who lay nights in front of her mother's bedchamber to waylay the drunken husband.

No doubt Mary was, in part, vindicating the abuses of her own life in her rebuttal to conservative Edmund Burke who considered primogeniture an anchor of social order, but she had known the "demon of property…to encroach on the sacred rights" of legions of unhappy men and women.

"I glow," she cried, "with indignation!"

------

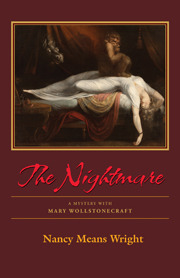

Nancy Means Wright's latest novel is The Nightmare: a Mystery with Mary Wollstonecraft (Perseverance Press, September, '11). www.nancymeanswright.com

Published on August 15, 2011 04:00

No comments have been added yet.