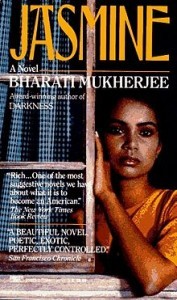

J is for juxtaposition: Rest in peace, Bharati Mukherjee

In 1989 when Bharati Mukherjee’s Jasmine came out, I was also coming out: a college sophomore already defining myself as a lesbian feminist; an Indian American defining myself as a writer who had never come across an Indian American book. The story of Jyoti escaping Indian patriarchy, passing through ever-more-liberating phases as Jassy, Jazzy, Jase, Jasmine, and finally Jane, resonated with me. I had attended elementary school in her Iowa; my young mother might have crossed paths with this mirror-image young woman, both of them wearing thick snowboots to the Woolworth’s and the grocer’s, where they would not have found the spices of home, not even fresh garlic. Plus, she had sex. An Indian girl! Sex! Nowhere else was this narrative visible, though so many of us were secretly living it; no one else was writing a brown female body moving through its lusts and hurts in white (so much more white than now) America. Soon afterward I had my ‘ethnic’ awakening and joined the chorus of campus critiques. Jasmine was a regressive narrative, one that would dominate Asian American fiction for several decades: oppressed Asian leaves home, finds freedom in America. A few sulky Asian American male writers also decried it from their this-is-why-we-can’t-get-laid position, refusing to acknowledge our communities’ patriarchies, and making a peacock-like display of their envy over the commercial success of such writers as Mukherjee, Maxine Hong Kingston, and ultimate literary world darling Amy Tan. The critiques had some valid and some not-valid aspects, but the debate had the unfortunate effect of lumping together authors who were actually quite different. By now we can see that Mukherjee was always much more intellectual than Amy Tan; her body of work shows a far broader range of characters and analysis. Most of her books grapple with the endlessly fascinating, still-unfolding epic of diaspora, but she resisted the simplistic and the banal. This complexity is evident even in Jasmine, her breakout book and perhaps still her most accessible one. It followed several novels and short stories that were more contained in scope, and in which Mukherjee tried out some of the ideas that populate the novel. Jasmine, which grew out of one of those short stories, touched me not only with its arc—which must be read, too, in the context of a feminist movement that was just surfacing the prevalence of sexual assault—but also with its sweep. It is an epic of shapeshifting, from Jyoti through Jassy, Jazzy, Jase, Jane, to Jasmine, unfolding a personality that, to paraphrase American Walt Whitman, contains multitudes. We see this ambitious scope from the first two words of the novel, “Lifetimes ago,” and open onto the village astrologer make a dire prediction. This exotic circumstance—banyan tree and buffalo feces and star-shaped wound all make their appearance on Page 1—became a trope of Indian and Indian American writing, so much so that I can hardly believe my own nonfiction book also begins with something like it, though by the time I wrote it, a dozen years and dozens of Indian American novels had intervened. Perhaps, duckling-like, I imprinted upon this first literary-mother? In both her book and mine, by story’s end, it is Destiny that must be overturned, in favor of a wild and wide-ranging free will: “Watch me re-position the stars,” says Jasmine on her last page. Mukherjee was a key figure in expanding the destiny of South Asian writing in the United States, a subgenre that has now bloomed far beyond those first narratives. Though many diverse genres, approaches, and characters now populate our collective literary corpus, it seems to me that Jasmine foretold much of it. We still have our assimilationist Janes and our sassy Jazzys and our traumatized Jases—all pushing, as if inevitably, toward our self-inventing Jasmines.