I have just started actually writing the book based on my Mellon Lectures in 2011 that I have been working on again these last 18 months thanks to the Leverhulme Trust.

The whole thing has come on a bit, and though I think anyone who attended the lectures will still recognise them (I haven���t changed my mind in a big way), I have put the whole thing together rather differently, and have loads more ���stuff���.

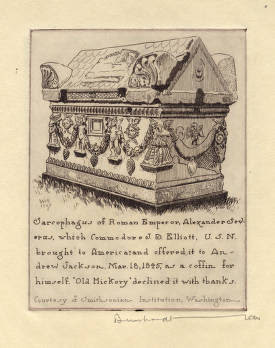

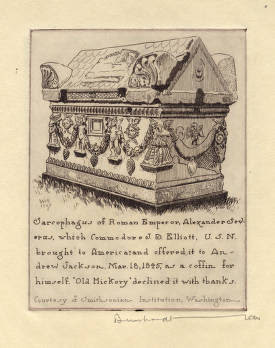

And a good example of that comes at the very beginning (ie the bit I have just written). I start the book in the same place as I started the lectures, with the great sarcophagus that used to stand outside the Arts and Industries building on the Mall in DC. It was brought back from Beirut, one of a pair, in the 1830s by Commodore Jesse Elliott, who had convinced himself that they belonged to the emperor Alexander Severus and his mother Julia Mamaea, who were assassinated together in 235.

True, the other coffin did have the name ���Julia Mamaea��� inscribed on it, but it also said that she dies aged 30 (which as one of Elliott���s more sceptical junior officers later pointed out), would have meant she gave birth to Alexander aged 3. Elliott was in fact making one of the classic mistakes in ancient history: to assume that any ���Julia Mamaea��� must have been THE ���Julia Mamaea��� (in fact there were 1000s of them). And anyway, the couple were killed somewhere in northern Europe, and the only ancient tradition on their burial has them buried in Rome not Beirut.

The interest though, as I had fun exploring before, is not so much in the misidentification, but in what Elliott planned to do with ���Alexander������s sarcophagus: namely give it to President Andrew Jackson to reuse as his own. The reason that it ended on the Mall was that Jackson said very firmly that he wasn���t going to be buried in something that had once held an emperor��� his Republican principles were too strong. So it got dumped on the Smithsonian.

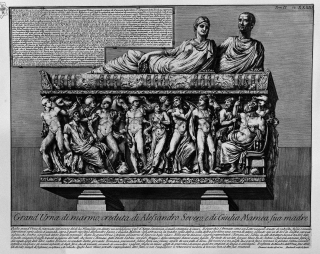

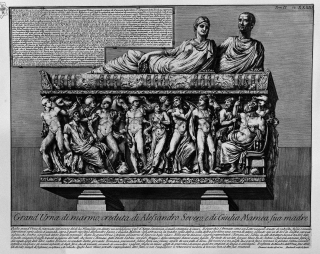

In the book, I have time to briefly explore another side to this story: the fact that at exactly the same time (unknown I am sure to Elliott, or else he was keeping quiet about it), there was a rival candidate for the sarcophagus of Alexander and Mamaea, found just outside Rome in the sixteenth century, drawn by Piranesi and now housed in the Capitoline Museum. This was apparently for shared occupancy, and the images of emperor and mother lie on top.

This is about as fantastic an identification as Elliott���s (and more upmarket nineteenth century guidebooks were already warning their readers not to believe it, even though there has been a recent attempt to revive it in the Journal of Glass Studies for 1990 if you are interested). But it has a UK/British Museum connection. Because another rumour was that the famous Portland Vase was found inside the sarcophagus and had once actually held the ashes of Alexander (and there have been over the years plenty of attempts to tie the design of the vase into a direct connection with Alexander ��� despite the fact that most people think it is about 200 years earlier).

Both are almost certainly mad misidentifications. But one of the things I am trying to do in the book is show how such misidentifications get a life of their own. So I think/hope they make a good start.

*************

And you can go here for the other format.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

excellent news, a new book :D

excellent news, a new book :D