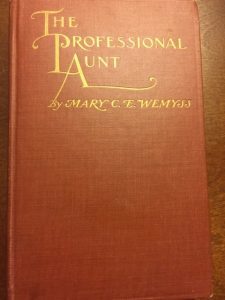

The Professional Aunt

dispatched from Key West by Barb

Over Christmas, my son Rob found a book in my mother-in-law’s apartment, titled, The Professional Aunt. He brought it to me because he found it funny. We have a long tradition of auntdom in our family, a role currently being vigorous pursued by his sister, Kate, with his daughter, Viola.

Over Christmas, my son Rob found a book in my mother-in-law’s apartment, titled, The Professional Aunt. He brought it to me because he found it funny. We have a long tradition of auntdom in our family, a role currently being vigorous pursued by his sister, Kate, with his daughter, Viola.

The book, by Mary C. E. Wemyss, was published in the U.S. in 1910 by Houghton Mifflin. The story is plainly set in England, and I’m guessing it may have been published there first. It’s a light, funny work of fiction, told in the first person, about the trials of a single woman whose sisters-in-law decide her perfect role in the family is to be the doting aunt. She, however, wants more, including the chance to have her own romance. She is constantly thwarted, until, of course, the end.

Here’s the beginning–

A boy’s profession is not infrequently chosen for him by his parents, which perhaps accounts for the curious fact the the shrewd, business-like member of the family often becomes a painter, while the artistic, unpractical one becomes a member of the stock exchange, in course of time, naturally.

My profession was forced on me, to begin with, by my sisters-in-law, and in the subsequent and natural order of things by their children–my nephews and nieces.

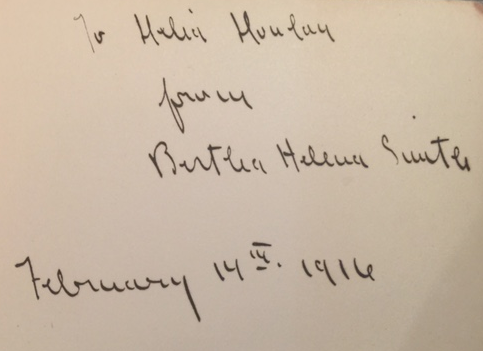

There’s a handwritten note in the front of the book that says:

The giver, Bertha Helena Smith, turns out to be easy to find. Various genealogical sites all confirm she was born in Vernon, Wisconsin on March 17, 1889 to Leander Smith and Helena Calvert. She married Barnhard Adelbert Clausius and had 7 children. She passed away on October 14, 1972 in Hillsboro, Wisconsin.

I had no luck tracking down the receiver, Melia Murphy. (If that’s even what that says. I can’t actually read it.) Poking around, I had the brainstorm she might be Amelia Murphy, but that got me nowhere. I would think a Murphy would be easier to find than a Smith, but let’s face it, neither one is a prize. When I am trying to make a suspect unGoogleable by my sleuth, my first choice is always a common name.

What route the book took from Wisconsin, if that’s indeed where it was given, to New England, where my mother-in-law purchased it, I can’t begin to guess.

The author, Mary C. E. Wemyss, proved much harder to track down than Bertha Helena Smith. Due to places like Amazon, eBay and Abebooks, books never disappear. But the author herself eluded me, though she was cited in at least two recent Ph.D. dissertations on the role of servants in literature. Finally, I spotted a reference to Mrs. George Wemyss, which got me to this.

Wemyss, Mrs George: Mary Lutyens (b. 1868) married George Wemyss. Eldest daughter among fourteen children (she had eight elder brothers).

So I guess she knew something about having sisters-in-law and being an aunt.

Then I found this:

MRS. GEORGE WEMYSS (1868-????), (pseudonym of Mary Wemyss, née Lutyens). Children’s author and novelist; sister of architect Edwin Lutyens; according to OCEF, her novels often focus on children; titles include The Professional Aunt (1910), People of Popham (1911), Impossible People (1918), and Oranges and Lemons (1919)

Her books don’t really focus on children, except one that is told from a child’s point of view. And then this.

[Mrs. Wemyss] is an Englishwoman with a most interesting personality. She comes of a Danish family the Lutyens and many of her ancestors have served in the English army. Her father was a soldier and when a young man serving in Canada was Master of the Montreal Hounds. After the Crimea he retired and became a painter and an intimate friend of Sir Edwin Landseer. He is now 81 years old and still rides to hounds.

So Mary Wemyss (pronounced Weems), author of more than ten books published in England and America, gets to be defined for posterity in terms of her husband, brother, and father. Admittedly her brother (of the ubiquitous garden benches) was pretty famous, but still.

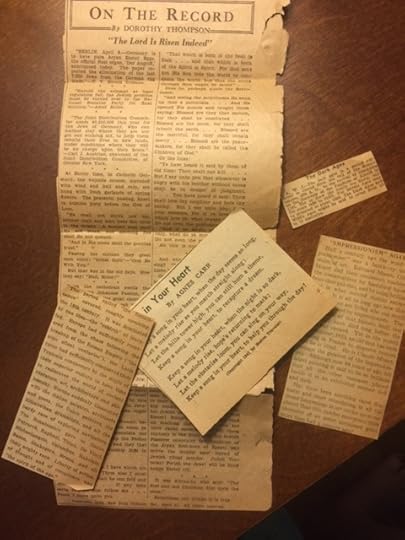

Tucked into the pages of The Professional Aunt, I found five newspaper clippings:

A definition of “The Dark Ages,” unknown newspaper, undated.

A definition of “The Renaissance,” unknown newspaper, undated.

An article about Claude Monet, still painting in France, at 80 years old, in part to prove to the world he is not blind. unknown paper, 1923, exact date unknown.

“On the Record, The Lord Is Risen Indeed”, by Dorothy Thompson, New York Tribune, April 11, 1936. A bone-chilling article about the successful removal of the Jews from the German egg trade, followed by a quote from Hitler threatening a “final solution,” and a plea for monetary contributions for Jewish resettlement. There follows a discussion of the celebration of Easter in the Catholic south and the Protestant north of Germany and how both have been twisted by the propaganda of Nazism. It ends with this quote, “It was Nietzche who said, ‘the first and last Christian died upon the cross.’ Sometimes one thinks it is true.”

“A Song in Your Heart” by Agnes Carr, Boston Traveler, December 1941, an inspirational poem about getting through dark times.

I leave it to you, dear readers to muse about Mary C. E. Wemyss, Bertha Helena Smith, Melia Murphy (?) and the person, whoever it was, who tucked those articles into the book. Whomever you imagine, I am sure they will be fascinating characters.

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Lea Wait's Blog

- Lea Wait's profile

- 506 followers