Shawn’s Question

In the Comments to an earlier post in this series, “Using Your Real Life in Fiction,” Shawn wrote:

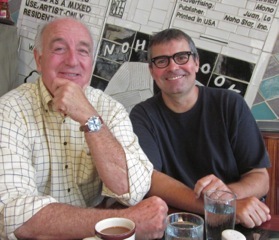

Steve and Shawn at the Noho Star at Bleecker and Lafayette, NYC

My question, which I think a lot of writers will have is this …

Do you deliberately think of this stuff re: characters and their thematic roles, before you write your first draft?

Or do you save this analytical/editor thinking for later? And then go back and tighten it all up?

Great question, pard. Lemme answer with a confession of exactly how dumb I am.

A few years ago I wrote a novel called Killing Rommel. (No, it was NOT one of the Bill O’Reilly series with “Killing” in the title.) Killing Rommel was a WWII story about a British commando expedition during the North African campaign of ’42-’43. Kinda like The Guns of Navarone, only set in the desert, with “Rat Patrol”-type jeeps.

The story was about a raid whose aim was to kill Gen. Erwin “The Desert Fox” Rommel, the German commander of Panzerarmee Afrika.

Here’s the confession: I had been working on the book for eighteen months (seven or eight drafts) before it occurred to me, “OMG, I’d better have my commandos actually have an encounter with Rommel.”

In other words, I had left that little item out.

So, to answer your question, Shawn: “No, I don’t always plot all that stuff out in advance.”

How about in The Knowledge?

On this one, I’d say I planned it to about the 50% level. I had the interior story down cold—and most of the elements of the exterior story. I knew what “Stretch” (the character that was me) represented thematically, and Nicolette and Marvin Bablik and Peter and Marty my agent and Teaspoon my cat, sort of.

But again, the most important piece of the story eluded me.

I’m talking about the relationship between Stretch and Bablik.

This may be a pattern with me. Maybe it’s common to a lot of writers. I tend to miss the element that’s right in front of my face. It’s like a fog or a blank spot.

I was maybe three months in to writing The Knowledge when it began to dawn on me not only that a friendship was developing between Stretch and Bablik, but that this was the most important element in the book.

In that instant, Shawn, I did pull back, as you say, to the “30,000-foot view” and ask myself

What does this friendship mean?

How does it play thematically?

Is it just an accident or should I jump on this and really beef it up?

I decided that this element was happy serendipity. I lucked out. I stubbed my toe on gold.

I suddenly realized that a huge architectural element in the story was that Bablik, like Jesus, was going to take on Stretch’s sins and, by his own self-immolation, atone for them, at least partially.

Suddenly The Knowledge became a buddy story. At the center, I realized, was an unlikely pair like George and Lenny in Of Mice and Men or Ishmael and Queequeg from Moby Dick. One was going to save the other.

In other words, the narrative element originated with instinct (I was just writing scenes and letting characters talk), but then I pulled back, figured out what the element was, and deliberately went forward trying to enhance it.

I asked myself, “How can I make these guys bond with each other in a way that’s not sappy or treacly?”

Chapter 13, Bablik gets furious with Stretch for having sex with a girl in the back seat of his taxi cab. “You’re like a son to me. Stop with these skanks! Have some respect for yourself!”

Chapter 21, Stretch’s uncle warns him for the third time to stay away from Bablik. “He’s a gangster. And his brother’s worse.” But Stretch doesn’t listen. Chapter 15: “I like the guy. He’s in the shit. He’s suffering.”

Bablik cooks eggs for Stretch at his hideout in Westchester. “He cuts the omelet in half with a Case pocketknife. He gives me the big half and slides the smaller onto his own plate.”

Why did I have Stretch sleep with Bablik’s wife? Partly because it was a fun scene, but mainly to deepen the bond between them, when Bablik finds out and forgives Stretch. Bablik offers Stretch his AK-47 for protection. Stretch declines. “Too bad,” says Bablik. “You were this close to becoming a gangster.”

In the end I loaded up the story with a number of asides (and no few overt statements and acts) that showed that each one of these characters cared for the other.

More than that, I strengthened their parallel arcs. Each character was dealing with extreme guilt over a crime he had committed, which only he knew about. Each one was desperate to redeem himself. Neither one knew how.

For the entire second half of the story, Stretch is trying to save Bablik from a headlong rush to his own extinction. In other words, he’s trying to save himself.

Like I say, Shawn, I missed this parallel story completely at the start. I was months into the writing before I felt the first glimmer.

So what’s the answer to your question? I guess my method is to do both—to plan from the start as much as I can, but not too much … not so much that I don’t leave room for instinct and for happy accidents.

And when those accidents happen, I try to be alert for them and to pull back at once to 30,000 feet and ask myself the left brain/editor-type questions:

What does this accident mean?

Is it important? Is it on-theme?

Should I drop everything and focus on this alone for a while?

P.S. My favorite moment in The Knowledge comes near the end, the last words that Stretch and Marvin Bablik exchange, at the Waldorf-Astoria before Bablik heads onstage to collect his big award, after which (and he knows it) he will be killed.

“What’s your first name?” he says. “I’m sorry, I never asked.”

“Steve.”

“Steve.” He holds out his hand. “I’m Mordechai.”

That wasn’t planned.

[P.S. As this post hits the air, Shawn and I are indeed having breakfast at the Noho Star. I’m in town from LaLa Land. It’s great!]