Trying to Make It Real…: Remembering Eugene McDaniels

Eugene McDaniels' legacy is most pronounced as one of the figures in American pop music history who paid a direct price for his willingness to challenge both the recording industry and the political status quo. That McDaniels lived to tell, speaks volumes about the artist's ingenuity, perseverance, and convictions.

Trying to Make It Real…: Remembering Eugene McDaniels by Mark Anthony Neal | NewBlackman

There is likely not a day when Eugene McDaniels' music is not recalled on some Robo soft-Rock station, during a non-stop mix lodged between Todd Rundgren's "Hello It's Me," and The Cornelius Brothers & Sister Rose's "Treat Her Like a Lady." Such is the fate of "Feel Like Making Love," the chart topping pop confection from 1974, that cemented Roberta Flack's position as one of the most important pop stars of the 1970s, and is perhaps, McDaniels' most well known composition.

As a songwriter and producer, McDaniels, who passed away recently at the age of 76, could hang his hat on the longevity of the song—it has been recorded by artists as diverse as Jazz vocalist Marlena Shaw, George Benson (during his programmed pop period in the 1980s) and D'Angelo—and the Grammy Award nomination that it earned for Flack. With songwriting and productions credits on recordings, spanning four decades, from the likes of Melba Moore, Phyllis Hyman (the gorgeous "Meet Me On the Moon"), John Legend, Della Reese, Donny Hathaway, jazz artists Les McCann, Eddie Harris and Bobby Hutcherson, Meshell Ndgeocello, Nancy Wilson and most famously Flack, McDaniels surely had a career that was as notable as it was enviable—no matter how obscure McDaniels might have been rendered throughout the years.

Yet McDaniels' legacy is perhaps most pronounced, well beyond the archives of ASCAP and BMI, as one of the figures in American pop music history who paid a direct price for his willingness to challenge both the recording industry and the political status quo. That McDaniels lived to tell—thriving on his publishing royalties and later influencing a generation of Hip-Hop era producers and artists—speaks volumes about the artist's ingenuity, perseverance, and convictions.Born in Kansas City in February of 1935 and later raised in Omaha, Nebraska, McDaniels sang in his father's church; his father was a Bishop in the Church of God in Christ (COGIC). After studying at the Omaha Conservatory of Music, McDaniels, then known as Gene McDaniels, moved to Los Angeles at age 19. While in Los Angeles, McDaniels connected with pianist Les McCann, who would figure prominently in McDaniels' career for the next two decades. Though McDaniels was perhaps most at home in the Jazz idiom, with a four octave voice—mellifluous is the term often invoked to describe his instrument—McDaniels could literally sing anything he wanted.

By the beginning of the 1960s, McDaniels was ensconced on the pop charts with songs like "A Hundred Pounds of Clay," and "Tower of Strength." Part of the success of McDaniels' early recordings is that his voice betrayed any hint of his racial identity—he could have easily been mistaken for singers like Bobby Vinton or Andy Williams. In an 1994 interview with the Los Angeles Sentinel McDaniels admitted that Liberty Records, his label at the time, "didn't make a deliberate decision to hide his race from audiences," but that they also were also "in no rush to get publicity photos" of him out to the press.

Despite his relative mainstream success, far removed from the revolutions in pop sounds that were occurring in Detroit and Memphis, McDaniels career at Liberty Records came to an abrupt end in 1963, when he sued the label for back royalties, noting the still continuous practice of labels charging artists for traveling expenses and production costs against their royalties. This would not be the last time McDaniels would spar with a recording label. As McDaniels told Kansas City's Pitch Magazine in 2001, "We are in the slavery business…the major record companies are slave owners. Artists have next to no rights to their own material."

Without a recording contract, McDaniels retreated back into the world of the Los Angeles Jazz scene honing his songwriting skills and, like many Black men of his generation, being profoundly affected by the Civil Rights and Black Power struggles. Early evidence of McDaniels' political transformation is heard on vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson's 1969 album Now, for which McDaniels provided original lyrics and vocals on tracks like "Slow Change," "Black Heroes," and the title track—all with nods to the Jazz vocal ensemble recordings of trumpeter Donald Byrd and the Free Jazz movement.

In this period in the late 1960s McDaniels wrote the song "Compared to What?" The song was initially recorded and released by Roberta Flack on her debut album First Take (1969), the first of many of McDaniels' compositions that she would record, as she came to function as his muse for the mainstream pop career he couldn't sustain in the early 1960s. But it was with a second version of the song, recorded later in 1969 by pianist Les McCann and saxophonist Eddie Harris for their recording Swiss Movement, (live at the Montreux Jazz Festival) that the song took flight becoming one of the most important protest songs of the 20th Century; even actress Della Resse felt compelled to record the song as she did on her 1970 album Black is Beautiful.

At a time when Black folk, American youth, and anti-war protesters were literally taking to the streets, "Compared to What" offered a scathing critique of social realities in the United States, taking aim at religious zealots ("poor dumb rednecks"), "tired old ladies" and the Vietnam War. Per the song's lyrics, McDaniels' understood the risk of raising questions about the war in Vietnam; it was thought by some as an act of treason, a notion that gained increased relevancy in the post 9-11 era, when many raised the similar questions regarding the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and Libya.

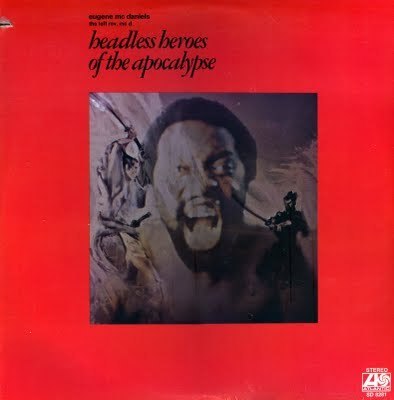

The success of the McCann and Harris recording of "Compared to What?," began a new phase in McDaniels' career as he signed with Atlantic Records (label home of Aretha Franklin, Donny Hathaway and Flack), now recording as Eugene McDaniels. McDaniels recorded two discs for the label, Outlaw (1970) and The Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse (1971).

For those expecting the McDaniels of "A Hundred Pounds of Clay," they might have been surprised by the opening and title track on Outlaw, when he sings "she's a nigger in jeans…" leading the Washington Post to suggest, after catching a few of McDaniels' sets at Washington DC's legendary Mr. Henry's in June of 1970, that his "songs are filled with words and imagery that some may find difficult to take, but they concern some of the most important issues of our time." McDaniels had no illusions about the shift in focus of his musical career: "I'm not out here to make any money. I'm out here to have some fun and tell the truth."

If Outlaw was provocative with its lyrics, McDaniels' follow-up, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse was both more musically and lyrically provocative. Forty years after its release, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse remains one of the most blatantly political musical tomes ever released commercially by a major label. The album contained critiques of blue-eyed soul ("Jagger the Dagger"), examined the phenomenon of "shopping while black" ("Supermarket Blues")—years before "racial profiling" entered into the national lexicon—and the futility of race hatred ("Headless Heroes").

"The Parasite" was McDaniels' most stinging critique though, as he gets at the root of American Imperialism and its relationship to the genocide of America's native populations. On the track McDaniels describes some of the early settlers as "ex-hoodlums" and "jailbirds" who used "forked tongues" in their drive to pollute the water and defile the air. Referencing America's ideology of "Manifest Destiny" McDaniels sarcastically sang that as "agents of God, they did damned well what they pleased." To capture the annihilation brought upon the Native populations, McDaniels plucks a stringed instrument in a way that replicates Native resistance by way of bow and arrow.

Shortly after the release of Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse, McDaniels was unceremoniously "dropped" from Atlantic. McDaniels apparently caught the attention of the White House with a not so thinly veiled shot at the Nixon administration and their "Law and Order" domestic policy ("rewriting the standards of what's good and fair/promote law and order/let justice go to hell"). As the story goes then Vice-President Spiro Agnew reached out to Atlantic founders Armet and Neshui Ertegun and McDaniels was released from his contract. McDaniels recalled thirty years later, just as Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse was being issued on CD for the first time on former Atlantic staffer Joel Dorn's Label M, "It was a black man in open, conscious resistance of the power that was trying to keep him enslaved—that was me…At last I had a chance to say what I believed in my deepest heart about politics, slavery, and about the genocide of Indians." (Pitch Magazine, 2001)

Even with the setback, other artists began to record McDaniels' songs; his "Sunday and Sister Jones" appears on Flack's 1972 album Quiet Fire (he also sings backup with McCann on "To Love Somebody") and also contributed "River" on Flack's career defining album Killing Me Softly (1973). "River" was also a track that McDaniels recorded with the group Universal Jones for their eponymously titled album from 1972. The album captured the vocal ensemble style that McDaniels featured on his album with Bobby Hutcherson, with a musical style that was much more accessible than his solo work with Atlantic.

With his political points made, McDaniels seemed to be trying to find a way to function with the recording industry on his own terms. When Universal Jones failed to make a mark, he got serious about the business of song writing, though he did make one last recording in the period with the provocatively titled Natural Juices (1975), which featured equally provocatively cover art of a scantily clad McDaniels. The album opens with McDaniels own take on "Feel Like Makin' Love," and also includes "River," which by 1975, had been transformed in a way that was not unlike the increasingly dynamic versions of "Ol Man River" that Paul Robeson performed throughout his career.

Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse might have remained an obscurity if not for the crate diggers of the late 1980s and early 1990s who liberated it from the metaphoric dust bin. Out of print for more than 20 years, Headless Heroes of the Apocalypse found its way into the music of A Tribe Called Quest, Organized Konfusion, The Beasties and Pete Rock and CL Smooth as samples. The original recording quickly became a collectable (s/o out to John Roberts) and bootlegged CD pressings of the album also appeared. In his 2001 profile of McDaniels in Pitch Magazine, writer Shawn Edwards notes the irony that Atlantic continues to collect royalties for the album's sampled use.

When Coke decided to launch an ad campaign in 2003 featuring "Compared to What?" McDaniels' profile increased. The intent of the song seemed lost on a generation of caffeinated fizz drinkers, even as the campaign, which featured Common, Amel Larrieux, Angie Stone and Musiq, was released as it was increasingly clear that the United States was going to invade Iraq. Even as it was being reclaimed, the song, and to some extent, McDaniels' legacy was being gutted of its political impulses.

Thankfully, Eugene McDaniels, lived long enough to hear Meshell Ndegeocello's brilliant reading of "Compared to What," on the soundtrack of Talk to Me, the biopic of one of McDaniels' political contemporaries, Petey Green. Just this past year, McDaniels also witnessed the release of the John Legend/The Roots collaboration Wake Up!, which featured a version of "Compared to What?." In the weeks after the recording's release McDaniels even took to Twitter to voice his pleasure with a generation of musicians who had discovered the value of his music.

The reality is that Eugene McDaniels never stopped making music, even if we were no longer paying attention. Through social media, in his later years McDaniels began to circulate his music and ideas via Youtube and his website GeneMcDaniels.com, including his most recent full length recording Screams and Whispers (2005).

Over the span of nearly sixty-year career, Eugene McDaniels lived by the mantra of his most important recording; he simply tried to make it real.

Published on August 05, 2011 19:01

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.