Reading from and Reading To

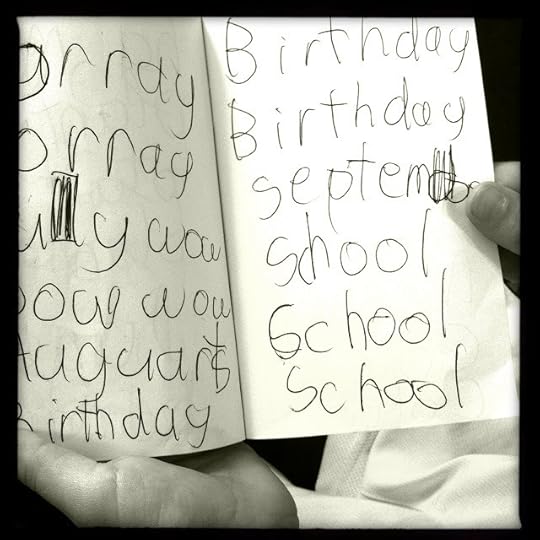

Extract from Abby Cook's Poem "The Twelve Months of the Year" as Held by Abby (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 31 July 2011)

Extract from Abby Cook's Poem "The Twelve Months of the Year" as Held by Abby (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 31 July 2011)I've been back, for the past two days, from the Boston Poetry Marathon and BBQ, a three-day extravaganza of poetry readings, featuring nearly 100 poets, and I was there for all but the last seven of them. The call of the road, the three-plus-hour drive back, encouraged me to leave a little early. Still, I was quite tired from late nights, poor sleep, and last night I fell asleep at 6 pm while reading a book and did not awake until 1 in the morning, at which point I read my book until 3:30 in the morning, finished it and returned to sleep. I cannot be filled with enough words to keep my dreams going long enough.

Any reading, by any poet, makes me consider the act of reading a poem aloud and returns me to my discomfort with it. I make this point with trepidation, but I've made it before. I've gone to many poetry readings, but I feel incapable of taking them in. I find it almost impossible to take in any information in a poetry reading, even a reading of a simple poem. I don't know if it is because the spoken word made a bit ornate or a little crooked (and intentionally so) is just too difficult for me to put together or if there is something in the cadence of a regular poetry reading (something Christian Bök calls Episcopalian in manner) that keeps me from latching onto sense for more than a few lines. Maybe it is that a poetry reading is usually a disjunctive experience of verbal movement but physical stasis. I don't really know.

But the poetic word in flight is uncatchable to me, or usually so. Just as it took me quite a few minutes to finally capture the little bat flying around inside these rooms I inhabit tonight, it takes me a while to capture the sense of a poem. And with a poem, as with a bat, it is easier to catch if not in flight. A bat crawling across the floor or a poem on the page is easy prey. Either in flight is elusive.

I will try, over the next few days, to consider some of the readings I experience this past weekend, but there were so many that it will be difficult. Even my notes are of little help, since they consist merely of descriptions of people's voices and snippets of their poetry that captured my imagination. (Of course, such note-taking cannot be conducive to a solid experience of the poetry reading itself, but I am compelled to capture some notes. And I further degraded my attention by photographing poets as they read and by occasionally capturing audio or video of their performances. So everything I write must be taken in the context of my unacceptable multi-tasking.)

At the marathon, I noticed that most people seemed to be able to take in the poems they heard and make sense of them. They all seemed better at this than I was. It was as if I were aurally dyslexic, unable to make sense of the word unless it were no longer natural, no longer spoken, unless it were fixed in place upon a static plane.

When I helped prepare some of Nancy's students for a poetry reading they'd be giving, I gave them some basic advice. 1. Figure out how you feel comfortable standing. 2. Speak so you can be heard. 3. Read your poems as if you love them. If they are sad, read them as if you love how sad they are. Make them as sad as possible. If they are dense and inscrutable, read them so their words can be understood, so that people can feel their cryptic nature. If they are boisterous, yell them out. This last point means that you have to understand the character of your poems and perform them in a way to support and extend them, to make them real, to make them palpable.

Many poets are quiet readers. And quietness is not necessarily bad, but all poetry can't be quiet. Much might be meditative or cerebral, but some must be emotional or humorous or boisterous. There must be a range to poetry that exceeds the voices we usually bring to it. And I'm looking for a poetry made real, made live. In a reading, I'm looking for a poetry of the body, a poetry wherein the body makes it real. This is a different poem than the subvocalized poem the silently reading mind lifts temporarily off the page. This is a poetry where the lungs and the heart and the muscles encircling bones bring the poem forth.

Why do I want this? Because I want a poetry for the audience, not a poetry for the poet alone. Often poets seem, to me at least, to be reading for their own benefit, to feel a bit of attention, to hear their own words, to feel some accomplishment, rather than to give the audience an experience to move them, to shock them, to make them hear the poem, sure, but also to feel the poem coursing through their bloodstream, to breathe the poems into their bodies.

I believe and I desire a poetry that is a performance, a performance of the body and the mind, a performance of the voice, a simple dramatic experience. I believe in the stage and want a poetry of the stage.

So that is what I attempt myself, and I make no claims to success myself. I am always barefoot in a reading so that I can stabilize myself on the stage. I usually display visual poems, perform a textual poem, and sing an extemporaneous poemsong, because I believe in a range of poetry and I believe that variety helps fight an audience's natural tendency to boredom. I wander the stage, mostly because I don't like being still, but also so the poem seems somehow alive (but I sometimes think I seem more like a caged lion that is unable to be the grand self it desires to be but can never be). I sing or I yell. I usually sing at the end of a reading. And I always leave the stage now and either return immediately to the audience or leave the room, spurning the sound of applause, melting back into the world.

It is, of course, ridiculous to do all of this. I am sometimes, if not always, overly dramatic and given to spectacle over substance, though I am one who sees surface as substance. I am a performer by nature, someone trying to find a way to entertain. Because if poetry isn't entertainment, I don't know what it is. Some entertainment is serious and severely intellectual and some is light and humorous. Poetry can be all these things, and if performed it should make any of these states of being deeply palpable.

And one poet I think did this at the past reading was seven-year-old Abby Cook, who performed with liveliness and beauty her deftly simple, pretty, and humorous poems. More about her and many of the other poets in the near future.

ecr. l'inf.

Published on August 02, 2011 20:28

No comments have been added yet.