Eight lessons from Nazi Propaganda

On my way through Austin, Texas last week I had a free afternoon and on a whim went to the Bullock museum of Texas History. To my surprise there was an entire exhibition about Nazi Propaganda, called State of Deception. It’s seemed timely somehow, so I bought a ticket and stepped inside.

Here is what I learned, in eight points.

Germany, as a democracy, was a world leader in the 1920s in media and mass communication technology. It had more newspapers (4700) than most nations in the world. It pioneered improvements to radio and television, the high-tech of the era. Its internationally acclaimed film industry ranked among the world’s largest. It was a technological and communication leader on the planet.

After the great depression (1929), German citizens were divided between left and right. Millions found the simple messages of Nazi propaganda appealing in times of economic hardship and instability. They left mainstream parties to support Adolf Hitler.

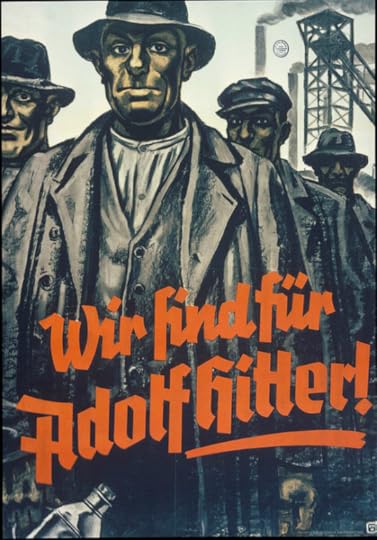

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time explicitly racist posters were also being widely distributed.

The Nazis’ platform did not initially scare many voters. While many voters weren’t necessarily at first attracted primarily to racist themes, they were willing to overlook them in hopes of economic promises. The Nazi’s carefully crafted different messages to different audiences, using nuance to signal to their deepest supporters without offending more moderate voters. This poster at right (“We’re for Adolf Hitler”) was aimed at unemployed coal miners, suggesting a vote for Hitler would bring their jobs back. At the same time explicitly racist posters were also being widely distributed.The term propaganda was originally a neutral term for the dissemination of information in favor of a cause. In the 1900s the term took on a negative meaning “representing the intentional dissemination of often false, but certainly compelling claims to support or justify political actions or ideologies” (wikipedia).

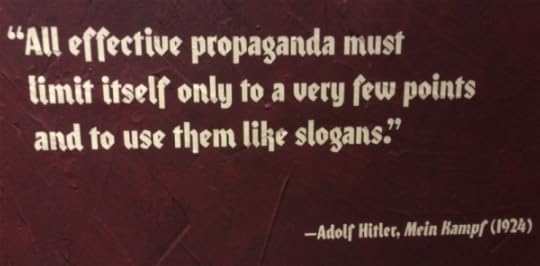

Propaganda, by definition: plays on emotions over facts and mixes truths, half-truths and lies. Hitler, and his propaganda minister Goebbels, had a deep understanding of mass media. They masterfully offered an appealing message of national unity and a utopian future, while simultaneously targeting the brutal persecution of minorities and anyone who disagreed with, or competed against, their ambitions for power. Outsiders and minorities were an easy target to blame for national problems, or the failure to fix them.

In 1933 a fire at the parliament was used as an excuse to suspend the German Constitution. The fire was claimed to be the beginning of a communist revolution, allowing Hitler, only chairman at the time, to convince the president to use article 48 to suspend many elements of democratic process, giving the president near dictatorial powers. These powers were never released.

Within months the Nazi regime destroyed the country’s free press. There were no longer alternatives to propaganda, making it harder to recognize. The regime closed opposition newspapers, forced Jewish-owned publishing companies to sell to non-Jews, and secretly took over established periodicals. By controlling the media there was no possibility of dissension. Questions could not be asked. Answers could not be heard. Citizens were not offered alternative views to consider nor the means to voice them. Power became unchecked. Challengers were increasingly easy to threaten, as news of their challenge, or imprisonment, would never be known.

In less than six months, Germany’s democracy was destroyed. The government became a single party dictatorship. Rights such as freedoms of expression, press, and assembly were revoked. Police established concentration camps to imprison those deemed to be “enemies of the state” which included intellectuals, teachers, writers and artists, among those chosen simply because of their race or ethnicity.

An online version of the exhibit can be found here including a powerful archive of posters, signs and cartoons from the era as well as recommendations for supporting independent media in the US.

Published on November 22, 2016 09:18

No comments have been added yet.